Features

Making Sense of Mid-Century Modern

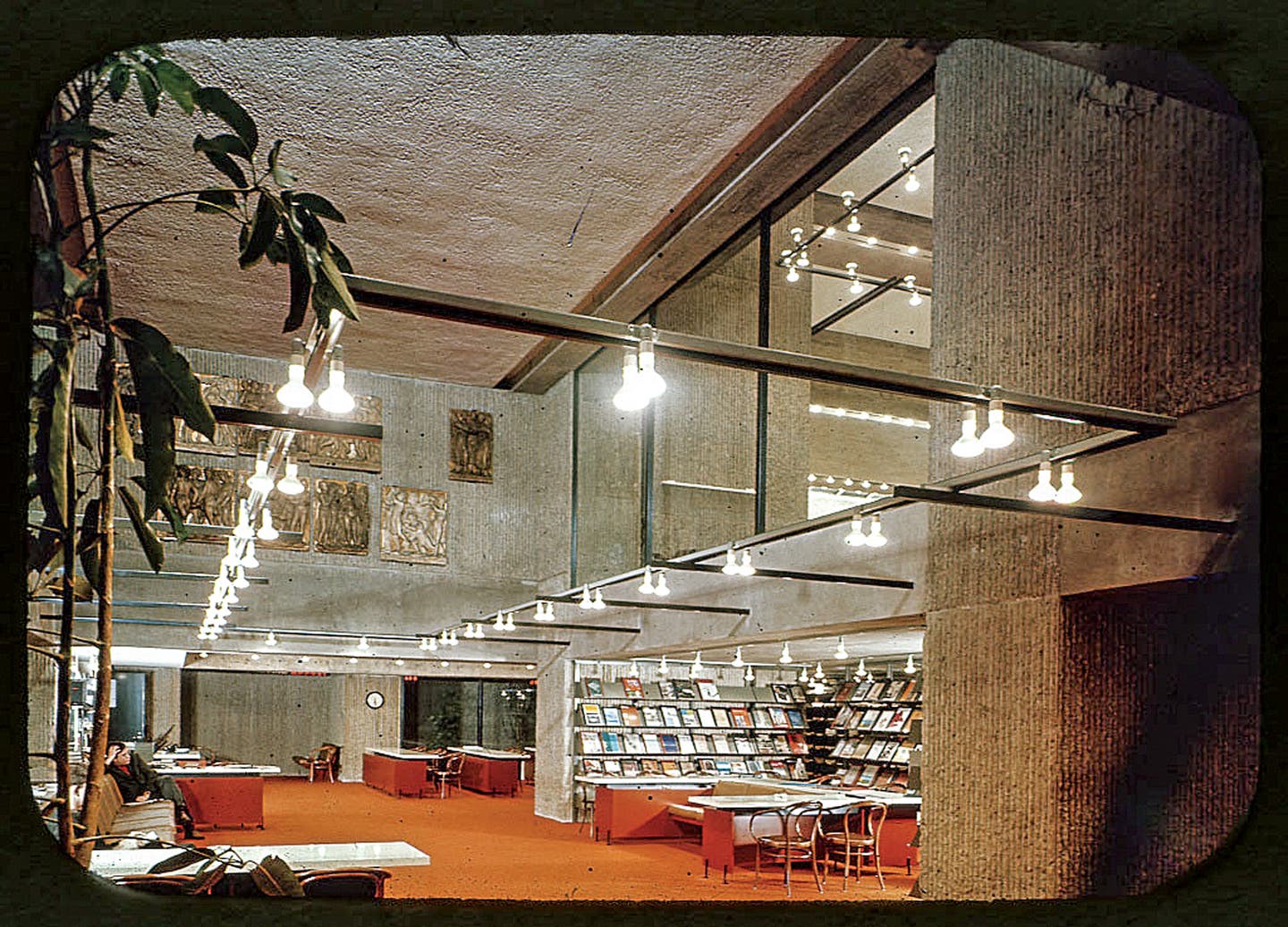

When the National Historic Preservation Act became law in 1966, historic architecture was generally viewed as something from the 18th and 19th centuries, the 1910s at the latest. Time moves on, and now the huge wave of 20th-century buildings once cautiously christened as Modernism or the Recent Past—if recognized at all—are attracting overdue attention in building surveys and websites alike under the rubric Mid-Century Modern. Here we’ll check in with some experts on where current thinking stands on this diverse group of buildings and what their future holds as they grow evermore a part of our architectural heritage.

No surprise for buildings often built within living memory, one of the first questions is What defines Mid-Century Modern? “It changes all the time,” says David Fixler, FAIA, a Boston-based architect who specializes in historic preservation and design, “but for us, it goes from the 1930s until the late 1970s, with the concentration being the post-World War II era.”

John D. Lesak, FAPT, principal, the Los Angeles office of Page & Turnbull, says he also views the term as a time period, and with much going on. “In the 1920s you have the International Style becoming the latest design trend and influencing how people think about buildings and the built environment in a very different way.” It was called International, he says, because the style enabled building anywhere, using systems to make up for regional climate differences—sometimes even cultural differences.”

Flora Chou, a cultural resources planner at Page & Turnbull and national board member of Docomomo US, agrees. “There are different sub-genres within the bigger, broader picture of Mid-Century Modern,” she explains. “When we think of Modern architecture, it starts even earlier, in the 1920s,” she says, referring to the Bauhaus school, the architects who led up to it, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Adds Thomas C. Jester, AIA, FAPT, a principal at Quinn Evans Architects in Washington, DC, “Modernism also encompasses Moderne buildings and late modern buildings from the 1960s and 1970s.”

After a global depression and World War II, materials and funding were in short supply so people began thinking in terms of economics as well as architecture. “In California, for example, they built lots and lots of campuses (partly in response to the G.I. Bill) and lots and lots of public buildings,” says Lesak, “while applying the stylistic learnings of the International Style, mixed and matched with regional variants.” Even with limited resources, he says there were still plenty of new ideas and a fair degree of experimentation. “In a sense, they applied war-related technologies to constructing buildings, rather than destroying buildings.”

Chou adds that the social component is evident in modern architecture too, in public housing, for example, but also for schools. “I think even more so in the post-war period, there was this idea that if a building is economical, it’s accessible to a lot more people.”

Historians debate what gave birth to the Mid-Century Modern period, but almost everyone agrees about the sea change that brought it to a close. “First, on the theoretical level, you had both the rise of post-Modernism,” says Fixler, “and people questioning the orthodoxy of Modern architecture in a very serious way.” Second, he reminds us about the oil crisis of 1973. “That oil shock changed forever the way construction was done. All of a sudden, these very light buildings, with single glazing and un-insulated walls, just didn’t work anymore, so architects had to re-think the paradigm.”

Perception and Practice

Mid-Century Modern buildings are clearly on the academic radar, but how does the practical and public world view them? Recalls Jester, “Back in 1995 and 2000 when we were organizing the Recent Past conferences for the National Park Service, it was almost as if we were talking about these buildings from a theoretical perspective.” He says there wasn’t a lot of project experience or projects that had been completed. “Compared to 15 or 20 years ago, today we’re a lot more equipped to deal with these buildings, both philosophically and technically.”

Buildings that are designated and significant are a much more acknowledged part of conservation practice, Jester says, but this doesn’t mean that there aren’t advocacy and preservation issues. “There’s kind of a duality here between the icons that are accepted and other buildings where there’s still a lot of pressure,” say from real estate development and demolition.

In Los Angeles, Lesak says he’s long observed a kind of Mid-Century pride among academics and fans of pop culture. “Every year there’s a big Modernism Week in Palm Springs, a tourist attraction and income generator for the cities. However, what we see, I think, is that interest doesn’t necessarily translate well to all of our clients.” The sense is many people who are in charge of educational sites and civic sites, or big commercial or corporate property holders—banks for example—don’t appreciate Mid-Century architecture yet and are often off-loading those buildings or demolishing them.

Chou says people may still argue about whether or not they like Mid-Century Modern, but at least they’ve heard about it. “Especially in California, there’s so much building from that period, it’s hard to see the examples that were very innovative at the time and that you want to save.” For perspective, she notes that back in the 1980s people did not think Art Deco architecture was worth saving.

Appreciation is one thing, but investment is another, which raises the question of whether Mid-Century Modern buildings are becoming a practice area for architecture firms beyond garden variety renovations. “I’ve been doing modern buildings for a long time,” says Fixler, “and, yes, it is a growing practice area.” He adds, “Twenty years ago we were voices in the wilderness, but obviously now we’ve got more company.”

Jester too says this building stock is definitely a larger part of the work at his firm. “We encounter these buildings on a pretty frequent basis. However, they do require some specialized skills and expertise to understand their design intent and the materials that were used—and in some cases find ways to repurpose the buildings and sensitively make modifications and upgrades.”

What’s more, he says there are definitely developers who are using the Federal Historic Tax Credits program to renovate modern buildings. “Our firm recently completed a project in Lansing, Michigan, called the Knapp’s Centre that, while built in 1937 (and so technically not from the mid-century) was definitely modern. The project required replacing all the concrete-backed porcelain enamel panels, but because we did it in such an accurate way with replacement material, the project secured tax credits.”

Make-Overs and Materials

Many historic buildings gain renewed life and economic viability when repurposed for different or improved uses, but as more Mid-Century Modern buildings outlive their original intents, they pose new challenges. In Fixler’s view, adaptive re-use of a modern building is, in some ways, no different than with a traditional one—taking a building built for one purpose and turning it into something else—but in other ways it’s trickier. “The difference is that an awful lot of modern buildings were more tightly designed to the program—literally form follows function—rather than just being generic space, as in a lot of mill buildings.”

Lesak puts it another way. “We have a saying, ‘Long life, loose fit,’ and some post-war buildings did have a tighter fit than their predecessors, so they’re not as easy to adaptively re-use.”

As Lesak explains, the floor plates of taller buildings built in the 1920s tended to have light courts and wings and be E-shaped in plan so that light and air could penetrate the building all the way through the floor plate. “However looking at Mid-Century high-rises, and how far air would flow into them if the windows actually opened, and how many people have views, they don’t really have those qualities. They have big, square floor plates and built parameters that are not as friendly to modern-day thinking about not only commercial office space but also general green-building principles.”

Adds Fixler, “One of the things that’s most difficult about Mid-Century Modern buildings are features like stairs, bathrooms, accessibility.” He says these are what’s needed these days to make a building legal, but were often not factored into the buildings of the 1940s, ’50, and ‘60s, so in many cases architects have to sacrifice program area to meet code.

“It’s actually a very creative, design-intensive process to be able to do this properly, especially without losing the essential character of the building,” he says. As a perfect example, he points to the addition to the 1963 Yale Art & Architecture Building. “Much of what the new addition does is just resolve all those code and access issues, which they couldn’t do within the building itself without destroying architect Paul Rudolph’s ideas.”

Even when the building’s use remains essentially the same, it’s not necessarily without conflicts. “Here in Southern California, where the aerospace industry and sciences have been big, we have many Research and Design laboratories built 50 to 60 years ago,” says Lesak. “They are more challenging to adapt because they just don’t have the infrastructure space built into them to accommodate contemporary equipment and safety requirements.”

Fixler faced this very situation in working with EYP on Louis Kahn’s Richards Medical Research Building at the University of Pennsylvania, which had originally been designed as a wet lab for chemicals, drugs and liquids that require ventilation and special plumbing. “Instead, with the full cooperation of the University, we were able to find a dry-lab use that was less system-intensive and better adapted to the open floor plates that Louis Kahn really wanted in that building.”

Materials—typically manmade and often synthetic—are another aspect of Mid-Century Modern buildings that can be as challenging as they are characteristic. “They may be experimental, or just don’t meet today’s best practice standards for how we would detail buildings,” says Jester, “so it’s not just the materials but also the assemblies and how the buildings are put together.”

This comes up frequently, he says, with curtain walls and stone-veneer cladding systems. He cites a 1976 late-modern building with a very thin, stone-veneer system that had basically failed over the last 30 years. “It was a very unusual system, where spray-foam insulation was applied to the back of stone veneer, which caused the stone to warp and permanently deform. So there’s been a lot of work to redesign that wall cladding system.”

Fixler suggests that there is, perhaps, less in a modern building that can be conserved in the manner of traditional, natural materials. “There are a lot more synthetics and materials that are going to break down, so you do a little more replacement than you do pure conservation.”

Another factor is improving energy efficiency. “When you’re dealing with first-generation curtain walls,” he adds, “there are no thermal breaks and no insulated glass, so they’re energy hogs. You want to improve the energy efficiency but, depending upon the stature of the building, that’s not always entirely possible.”

At the Richards Laboratory, for example, they opted for high-performance laminated glass and were very aggressive with systems, but kept the original, thermally un-broken frames because they were such an important character-defining feature. “We could have gotten by tearing out the original frames and putting in insulated glass. But then it wouldn’t look the same, and Richards being a landmark building, you couldn’t do that,” says Fixler.

As Chou explains, “Part of what makes some of these buildings significant is their experimentation with different materials and systems.” For example, she and Lesak say they sometimes see sandwich panels that, over decades, didn’t remain a sandwich, which begs the question of how to deal with them, including repair or replace?

Lesak says there’s even an ongoing debate in the preservation community about whether or not modern buildings should be treated using the Secretary of the Interior’s standards akin to traditional buildings. “I think more people are realizing that the approach is the same. If the materials are functional, and they’re doing their job, and they can be repaired, then you repair them. If, at some point, they no longer do their job and they have to be replaced, then you replace them, but in a way that’s sensitive both to the materials and the design intent.”

In fact, Jester, who edited the book Twentieth Century Building Materials, believes that the more iconic modern buildings—the masterworks of architecture—are in some ways the easiest for making such decisions. “It is well understood that they are to be treated in a very sensitive manner,” he says. “It’s the other buildings that may have some heritage value, but are probably not as highly significant, where the challenge is to find ways to modernize them so as to respect the original design while providing the continued life that serves the owners and users.”

For Further Information

Docomomo US www.docomomo-us.org

International committee for the documentation of buildings, sites, and neighborhoods of the modern movement.

Keeping It Modern www.getty.edu/foundation/initiatives/current/keeping_it_modern/

An international grant initiative of the Getty Foundation that focuses on important buildings of the twentieth century.

APTI www.apti.org

Special technical committee on modern heritage.

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.