Profiles

The Jeffris Foundation

Advertising is fond of the phrase “Looks small, thinks big” as a tagline for high-tech products that are as powerful as they are compact, but it might apply equally well to philanthropic organizations like the Jeffris Family Foundation of Janesville, WI. Though overshadowed by the Goliaths of the giving world, and with a tightly focused mandate, it nonetheless stands tall in supporting historic preservation projects that are under-the-radar, but with outsized impact.

As Thomas M. Jeffris, President, explains, the Foundation was established in 1979 by his parents, Bruce and Eleanor, and Jeffris himself with some down-home goals. “The family felt that it wanted to improve the quality of life of the people of Wisconsin, and through preservation projects in smaller communities because, obviously, these don’t have the financial means of the big communities.”

The Jeffris family immigrated from Scotland to Wisconsin in the 1840s, he says, and has always had a strong Wisconsin commitment. In fact, Bruce Jeffris built a highly successful business career in the state, joining the Parker Pen Company of Janesville after World War I, then rising through the ranks of one of the world’s largest makers of high-end writing instruments to retire as Chairman of the Board in 1960.

Should the very mention of a foundation conjure up an organization with global numbers and reach, the truth is much more earthbound. “We’re not a big, huge foundation—no comparison with the likes of Gates or Rockefeller,” says Jeffris. “In reality, we’re very small, with just one, full-time staffer—me!” He adds that the Foundation has two directors which, with Jeffris, makes a board of three persons. “We’ve been told that we’re the only foundation of our size and focus in the nation.”

Jeffris says that when they hired a consultant to help with management issues, he reported back he couldn’t find any comparable organizations on which to base recommendations. With classic Midwestern geniality, Jeffris responded, “Well, do what you can.”

As he explains, “We just focus on doing a very few projects, but with relatively sizable grants, so we give away two or three large grants a year.” He says their largest grant to date—for $1 million, which approaches the amount they give for an entire year—went to the Cyrus Yawkey House in Wausau, WI, and helped the local historical society finish a $3-million restoration.

While some philanthropic organizations are a response to a crisis, such as a war or natural disaster—think Hurricane Harvey—the inspiration behind the Jeffris Foundation is much more low-key and local. “The money was gifted for the benefit of the people of Wisconsin and small towns,” says Jeffris, “and the preservation aspect just sort of evolved from there.”

As happens with many organizations, there was a natural tendency for the Foundation to follow the interests of its leaders, and Jeffris, one of the founders, had deep interests in historic preservation. After being appointed five times to the State Historical Society Board by Tommy Thompson, Governor of Wisconsin from 1987 to 2001, as well as being chairman of the local landmarks commission reviewing permits for historic properties, he says historic preservation “gradually became something about which I felt very strongly.”

In contrast to some architecturally oriented foundations that fund a wide range of project types across the country, the Jeffris Foundation keeps a tight rein on its largess. “Though in the past we have occasionally underwritten books and workshops related to historic preservation, we generally support just buildings, and those of regional or national significance,” says Jeffris.

That being said, in 2009 the Foundation expanded its scope beyond Wisconsin to Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri and Ohio, “but we stick to just this Midwest, eight-state region.”

Of course, grants don’t grow on trees, and at the Jeffris Foundation a grant is a two-way street that must be earned. “Applicants have to do a Historic Structures Report (HSR),” advises Jeffris, “and it has to be an excellent one.”

He says the most important criterion is that the Foundation fund projects with a comprehensive HSR that documents the history and condition of the property and recommends appropriate treatment of the building’s significant elements. “An HSR is the best means to prepare for and support quality restoration and rehabilitation efforts, including a path to restoration.” Separately, the Foundation looks for a detailed construction document itemizing window costs, roof repairs, and so forth.

The other quid pro quo at Jeffris is that applicants must fulfill challenge grants, a popular fund-raising mechanism for foundations and non-profits. Here, the grantor stipulates that before the applicant can receive any grant funds it has to raise a certain amount of funds on its own as described in the challenge—commonly in ratios of 2:1 ($1 donated for every $2 raised by the applicant), 1:1, or 1:2.

Challenge grants typically stipulate that matching funds must be raised within a specified timeframe and with periodic updates. The main advantage of challenge grants, of course, is that they bring in additional funds, potentially doubling or even tripling the amount of money raised, but they also increase participation and publicity at many levels.

The Jeffris Foundation limits funding to documented 501(c)(3) 509(a)(1) or (2) non-profit organizations. As outlined in the grant criteria, it does not fund privately owned sites, endowments to support specific properties or operations, maintenance or stabilization projects, acquisitions, debt reduction, or operating budgets. Most potential projects come though the Foundation’s own field staff, not unsolicited applications.

Given the generous figures of Jeffris Foundation grants, the bar for matching funds can, at first, be quite daunting for modest communities, but the results are nonetheless remarkable. “What I find absolutely unbelievable is how these people just rise to the occasion,” says Jeffris with evident pride. He notes that there have been some failures, which is to be expected, “but by and large these small Midwestern communities really come through, and about 90% of our challenge grants have succeeded.”

A case in point he says is the Keokuk Union Depot in Keokuk, IA. Designed by the famed Chicago architectural firm of Burnham and Root and erected in 1891, the Depot served all five railroads in this commercial crossroads for some time. Because of consolidations, mergers and bankruptcies over the years, by the 1960s it served only the CB&Q line.

In 2012, the non-profit Keokuk Union Depot Foundation was established to help restore the 178-ft. Romanesque Revival building, including its massive tile roof. “It was a $1-million project, and we gave a challenge grant of $330,000,” recalls Jeffris, “so they ended up raising some $700,000 in a town of 10,000 people! We find this kind of interest throughout the Midwest.”

Adds Janet M. Smith, president of the Depot Foundation, “The matching grant inspired the hope, now nearly fully realized, of actually being able to restore the roof to the highest historic preservation standards, including raising the central tower to its original height and using red clay tiles made by the successor maker of the 1891 tiles. This would not have been possible without The Jeffris Family Foundation.”

Though many historic restoration projects are dominated by the structural and mechanical needs of the building, Jeffris grants are by no means exclusively for the practical, as demonstrated by the Villa Louis Historic Site in Prairie du Chien, WI. Along with the Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT, and the Glessner House in Chicago, the interiors of Villa Louis are considered among the top examples in this country of the ideas of William Morris, the designer, purveyor and proponent of the English Arts & Crafts movement.

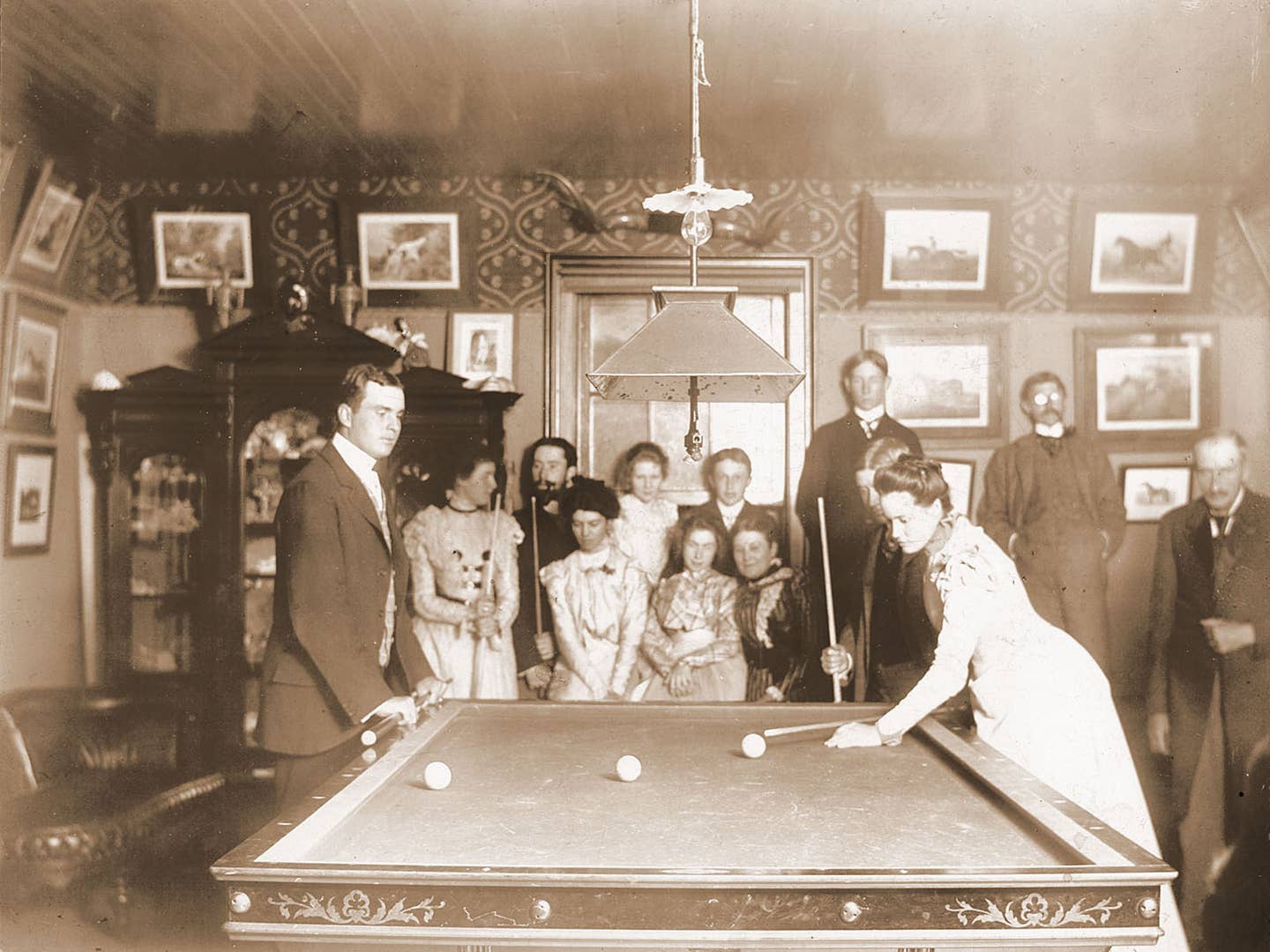

“The overall project had a very large, non-decorative component—electrical, HVAC, foundation repairs, wheelchair lift, painting—but that being said, close to 90% of the Jeffris Foundation funding was for decorative work.” According to Samantha Mantern, lead interpreter at the site, “These rooms were all completely transformed by the restoration,” adding that comparing a historic photo of the billiard room with the same room today shows the accuracy of the restoration.

The goals of a grant can seem even more uphill when the matching ratio is 1:2. At the aforementioned Yawkey House, the Jeffris challenge grant was for $1 million if the applicant could raise another $2 million. “A lot of the matching funds came from the Yawkey family, who originally donated the mansion to the historical society, but ultimately the campaign and the restoration were successful.”

In another instance, Jeffris recalls a grant where the town had three years to raise about $100,000 before the Foundation would give them $50,000. “At first they figured, ‘Oh Tom, we’re never going to make it,’ but, to their surprise, they fulfilled the challenge in six months.” Later, the town reported they had only one regret. “I know, I know,” he shot back, “you should have asked for more money!”

After funding over 100 projects, Jeffris continues to be as amazed as he is pleased, “It’s always interesting to see how enthusiastic these people are about getting a large challenge grant for their local historic property—and from a foundation that nobody’s ever heard about.”

A Sullivan Jewel Box

One of the latest Jeffris Foundation grants is for 1914 The Home Building Association Company Bank (also known as The Old Home) in Newark, OH, one of architect Louis Sullivan’s late career “Jewel Box” banks. “This one is really special,” says Darryl G. Rogers, AIA, principal at Rogers Krajnak, Architects, Inc., of Columbus, OH, who points to the all-terra-cotta façade that is more ornate than the brick with terra-cotta accents seen on other Sullivan banks.

“It’s also a corner building, so there are two elevations that face public streets, and inside there are Sullivan’s hallmark stenciled murals with their geometric motif – all pretty amazing when you look at the detail,” he adds.

Though the building has suffered a lot of damage over the years, with many interior features altered or removed, computer images show its new future use as the home of Explore Licking County, the convention and visitors’ bureau. “It’s a great adaptive re-use project, and our client, the Licking County Foundation, is the right kind of steward,” says Rogers. “They know they’ve got something really special, and the grant from the Jeffris Foundation is really great news.”

Keokuk Depot Suppliers/Contractors

Preservation consultant, project manager - Restoric, LLC, Chicago

Dormer Windows – Adams Millwork, Inc., Dubuque, IA

Roof consultant – Allen Consulting Group, LLC, Wilton, IA

Roofer – Conrad Roofing, Inc., Chicago, IL

Roof Tile – Ludowici, Inc., New Lexington, OH

Crane Services for apex – McDowell Crane & Rigging, Keokuk, IA

Carpenters who built apex – Meyer Construction Guild, Skokie,

Glass for dormers – Double A Glass, Co., Keokuk, IA

Air Conditioning – Enderle Heating & Air Conditioning, Inc.

Fasteners for tiles – Fastenal, Inc., Keokuk, IA

Lumber – Hartricks Lumber Co., Keokuk, IA

Decorative finishes, faux graining - M. Weil Interiors, Evanston, IL

Engineer – TGRWA, LLC, Chicago

Brick – Gavin Historical Brick, Cedar Rapids, IA; Marion, Inc., Chicago, IL

Other – Thompson Carpentry, Inc., Skokie, IL; Prime Scaffolding, Inc., Chicago, IL; Complete Rental, Inc., Ft. Madison, IL; Midwest Storm Company, Dubuque, IA; Hamilton Lightning Protection, Eola, IL; Ray Bradley Hauling Rubbish, Keokuk, IA; The Schnitzelbank, Ft. Madison, IA

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.