Profiles

Profile: Jan Hird Pokorny Associates

JHPA’s portfolio reflects the firm’s seminal role in the preservation movement and the tenaciousness of its founder.

By Gordon Bock

For a field so imbued with the past, preservation is very young – barely half a century old – so it’s not easy to find firms dedicated to historic architecture through times when work was scarce and under-appreciated. Among the few who have continued to help define the discipline – indeed even create it – is Jan Hird Pokorny Associates, Inc. of New York. Not only does their project list read like a who’s who of landmark structures, the very history of the firm touches many of the premier buildings, people, and events that contributed to make historic preservation what it is today.

The origins of the firm are as colorful as its founder and the career path he helped blaze. Born in what was then called Czechoslovakia, Jan Hird Pokorny was a young man with a military commission by the advent of World War II – in, of all places, the Czech cavalry. “Unfortunately, Jan fell off his horse and was injured,” recounts principal Michael Devonshire, director of conservation, “but luckily, his father, who was a very important electrical engineer, had enough political pull to get Jan a sort of plum job where he commuted to headquarters but lived at home.”

Then the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in March of 1939. As principal Richard Pieper, director of preservation, continues the saga, “Seeing the future, Jan’s father got him sent to Sweden as an employee – presumably to study the subway system in Stockholm, which then was about four stops long – and thereby out of the country. With the help of a Swedish group who was getting Czechs to the U.S. on student visas, Jan made it to these shores, where he enrolled at Columbia University in New York City.”

While studying for a Masters Degree in architecture, on top of his training at the Czech Technical University, Jan took a course in historic architecture taught by no less an authority than Talbot Hamlin, the longtime Columbia professor, Greek Revival scholar and Pulitzer Prize-winning historian. This was in the mid-1940s, and well before the dawn of preservation as it is today. “I think Jan was next to the only student in the course,” says Devonshire. “Under Hamlin, Jan studied and documented several historic buildings in Manhattan and greater New York, such as the Morris Jumel Mansion; later, he would return to actually work on some of those very same buildings.”

After starting his own firm in 1947, Pokorny began specializing in the restoration and adaptation of historic structures for reuse in New York, including several significant educational commissions, such as the master plan for Lehman College and the renovations at Lewisohn Hall at Columbia. Then, when James Marston Fitch started the Historic Preservation Program at Columbia in 1965, the first such course of study in the country, Jan Pokorny was a natural as charter member of the faculty.

Down to the Sea at Schermerhorn

Fast forward to the late 1970s, when several future members of the firm all crossed paths at an auspicious historic site. “When I moved from upstate New York to Manhattan in 1979,” says Pieper, “I heard there was work going on at the South Street Seaport Museum.” As it turned out, the Seaport, now a prime attraction in lower Manhattan, was not as yet hiring. “However, they suggested that I walk over to New York City Maritime Museum, which in the day consisted solely of a ground-floor office on South Street.”

The timing was ideal because, even though the Maritime Museum was also still a-borning, the restoration of what is known today as the Schermerhorn Row Block was just getting underway. Once the heart of the teaming East River working waterfront, by the 1970s the block of early 19th-century brick warehouses and counting houses had become only derelict reminders of shipping in the age of sail. After narrowly escaping demolition in 1966, the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation singled out the block as the centerpiece of the future South Street Seaport District, and retained JHPA to provide a master plan and design documents for its restoration and adaptive reuse.

Since this included stabilization and careful research and reconstruction of missing historic elements, “Jan also needed help – especially on the materials side,” says Devonshire, who had been working with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, “so Pieper and I came in doing whatever we could.” Adds Pieper, “Michael and I pulled a lot of windows, disassembling them and documenting their construction for later work.”

Indeed, besides being the largest historic preservation project in New York City up to that time, the Schermerhorn Row Block and related structures were the sites of seminal research – “a living laboratory” as Devonshire puts it – and a growth project for many of today’s premier firms in the field. “It was a turning point for Jan’s office,” says Devonshire, “which had previously done more renovations and adaptations of historic buildings, and set the firm firmly on a course of preservation.”

The Schermerhorn Row Block also helped set a pattern for JHPA’s practice – that is, long-term relationships with clients and the ongoing stewardship of their buildings. Though the firm travels internationally, it has worked consistently with New York State Parks since the 1970s, as well as Monmouth County in New Jersey, and has regular clients in the Brooklyn Historical Society stemming from a Historic Structures Report in 1996.

A good example of a long-term relationship, and how it grows and changes with the client, is JHPA and the Olana State Historic Site, the 1870s home of the Hudson River School painter Frederick Church. The firm, which has been working at the site for over 18 years, just completed its seventh project, and designed and oversaw the restoration of the main building beginning in 2001. “That was a strict restoration,” notes Pieper, where, in order to conserve as much original fabric as possible, the process began with a hands-on survey of each brick on the polychrome, Moorish-fantasy building, and all of the woodwork, before proceeding with masonry re-pointing and woodwork repairs.

An Olana project of almost the opposite ilk, but no less meticulous, was the creation of a new education center at the site. Says, Pieper, “The rules are that they cannot build anything on the site that did not previously exist – no totally new structures – but they can reconstruct structures.” This became the premise for designing and reconstructing a wagon house that was once attached to an existing farm stable but long since razed. “The exterior makes fairly literal reference to the historic, though now demolished, building, but the interior is completely new for the education center.”

A similar project with an exterior restoration-interior rehabilitation duality was a cottage once occupied by Frederick Church himself. “We reconstructed a wing on the cottage that had been demolished,” says Pieper, “and rehabilitated the interior to serve as a board meeting room.”

Sometimes extended relationships are born of economic, as well as architectural, win-wins, and that is particularly true of the firm and ecclesiastical buildings. “It seems like we work on a lot of churches,” notes Devonshire, “though individual projects often extend over long stretches of time.”

Not surprisingly, the reasons why are related. While JHPA often receives referrals through the NYC Landmarks Commission and the city’s preservation network, both Devonshire and Pieper suspect that the firm’s reputation for creative budgeting helps spread the name through the religious community grapevine. “We may do a lot of work on a church or temple,” explains Devonshire, “but it’s divided into $30,000 and $40,000 projects because that’s the most many congregations can afford in one shot.” He adds, “Breaking projects into pieces over time is something other firms don’t always like to do, but we’re comfortable with scheduling in this way.”

No doubt the firm’s sensitivity to historic buildings is also part of the reason. A good example is the Church of the Incarnation in New York. Constructed in 1864 from a design by Emlin T. Littel, the church is renowned for containing decorative works by a pantheon of late-19th-century masters, from Tiffany, LaFarge and Morris, to St. Gaudens and Burne-Jones. The church was also FDR’s place of worship when he was in town, so when JHPA was commissioned to design an ADA accessibility ramp, the firm approached it as no small task. Nonetheless, “It was extremely successful, a wonderful design that earned awards from a couple of different groups,” Pieper says, “because it is extremely referential – not an easy thing to do without altering a building.”

JHPA also has a long association with another edifice cherished as a kind of artistic holy ground: the Church of the Ascension, also in New York. Designed by Richard Upjohn and completed in 1841, the church was updated in the 1880s by McKim, Mead and White, with interiors by Stanford White and John LaFarge, among others.

That is not to say that ecclesiastical projects don’t sometimes benefit from an inspired nudge. As Devonshire recalls, “When Pieper and I kept telling the Rector of a certain church (now a good friend) that he needed to do something with his building’s tower and spire – which is all brownstone, a material notorious for flaking to pieces – he kept putting us off.” It seems the Rector was very skeptical because he’d been through all this before with contractors, spending a lot of money for little results. “Then one day, when his wife was walking under the tower, a small piece of brownstone fell off and whacked her on the head,” says Devonshire. “From then on, we were in.”

We Have the Technology

Though the firm’s projects and expertise span a wide range of building types and activities, they are all linked by some underlying approaches to the work. “Jan Pokorny was an incredible perfectionist,” explains Devonshire, “and the firm is known in preservation for its ability to tackle unusual technical problems.” In the construction arts, solving technical problems often calls for an understanding of materials, and this too is JHPA’s forte. “We’re at home and in our ‘sandbox’ when materials are involved,” says Devonshire. “There’s not a material with which we don’t want to be involved.”

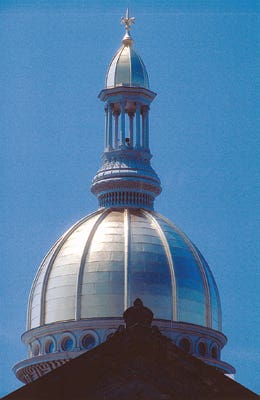

If you take the sandbox metaphor to its limit, then a project like the New Jersey State House dome must have been like the proverbial candy store. Originally constructed in 1792, the State House acquired an 80-ft.-high cast-iron and steel rotunda and dome in the 1880s following a massive fire. After more than a century of service, however, the exterior gilding was failing, so JHPA was commissioned to look at the condition of the entire dome.

“The list of materials we had to deal with at the State House is long,” says Devonshire, “wood, stone, cast iron, steel, concrete, copper, gold leaf, stained glass, and more.” Ultimately, the firm’s investigation revealed major deterioration of the structural steel supports for the dome, as well as the cast iron in the rotunda, leading to construction documents for their repair.

In the same league material-wise is the Battery Maritime Building. Built in 1909 as a gateway to lower Manhattan via ferries and elevated railways, it was designed in the Beaux-Arts style and is a veritable confection of early modern materials, from copper and stucco to the glazed-tile ceilings of the illustrious Guastavino vault system. Once the twin of the nearby Whitehall Terminal (lost to fire in 1991) the BMB smiles on New York harbor with an unmistakable façade of over 8,000 cast-iron and rolled-steel elements anchored by countless unabashed rivets.

JHPA was initially called in to survey the exterior and structural conditions of the BMB but, after finding severe deterioration and loss of architectural features from a 1957 alteration, wound up directing a full restoration of the building envelope and roof. “On many projects, you can visualize the ideal scope of work in about 40 minutes,” says Pieper, “but when you step back and take into account reality – budgets, schedules, logistics – that scope tends to change a lot.”

Such was the case at the BMB when it became evident that, in order to perform the necessary structural reconstruction, they would have to remove, and then reassemble, the building’s complex outer skin. “The challenge was actually two-fold,” according to Pieper. “First, client education – that is, explaining the need for the extra step of removing the outer skin; then second, doing the work.”

With their deep roots and experience in New York City and the Hudson River Valley, it’s easy to assume that JHPA is a team of regional and historical specialists, but that is far from the case. Indeed Jan Pokorny, who was a pivotal member of the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, and chairman from 1997 to 2007 (shortly before his death at 93), was equally well-versed with historic architecture abroad. “We’re not pigeon-holed into any one building type or era,” says Devonshire, who has worked on the restoration of Manitoga, the home and studio of the famous Modernist furnishings designer and producer Russell Wright.

The firm has been hired by the Maria Mitchell Foundation in Nantucket to survey buildings dating from the 1770s to the 1930s, and periodically they get called by the World Monuments Fund to inspect and advise on foreign structures. In fact, the Fund invited JHPA to help analyze and study Lednice and Valtice Castles in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which led the castles to be selected as a World Heritage Site. Jan Pokorny would, no doubt, approve.

Gordon Bock, author, consultant, and historian, lists his new lectures, appearances, and books at www.gordonbock.com.