Features

History Reinterpreted: The Myles Standish Hotel

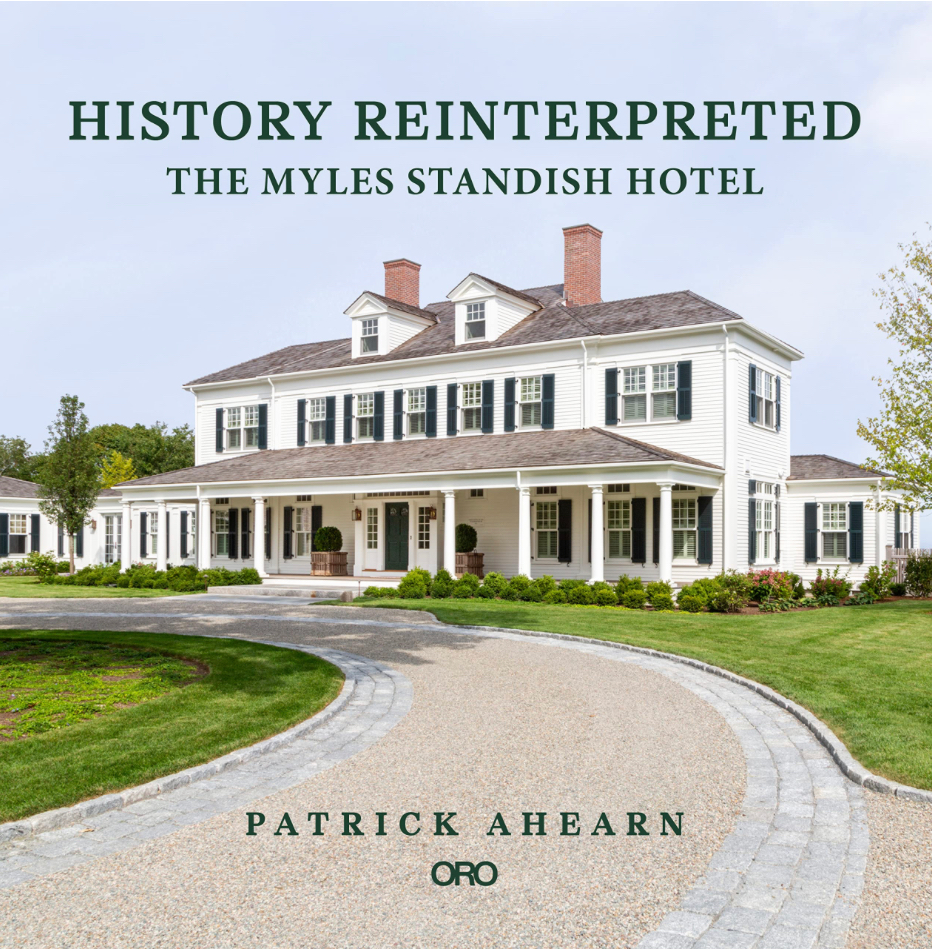

We’ve all heard of private residences that get repurposed into hotels: think countless B&Bs or even the now-infamous Mar-A-Lago. But what are we to make of a hotel adapted into a house? That’s the arc of the Cinderella story behind History Reinterpreted:

The Myles Standish Hotel by author and architect Patrick Ahearn, FAIA,

Boston-based, with a project list of landmark lodgings like Boston’s Copley Plaza, the Shoreham Hotel in Washington, D.C., and the Equinox Resort in Manchester, New Hampshire, Ahearn is also a long-standing Massachusetts resident (by way of Long Island, New York) and New Englandophile. Suffice it to say, he knows the architectural turf. Nonetheless, rather than being smitten by the vogue for contexualism—that is, referencing a structure’s surroundings to give its parts meaning—Ahearn explains that his favored design strategies are closer to home.

High on his list is to tease out the story of the house in order to pursue what he calls a “narrative-driven approach.” Here, his goal is to “capture the history of the place” for “authentic feeling design choices” so as to create a “plausible architectural execution” from some time in the past. Where no such source material exists, as in the case of a commission on vacant land, Ahearn doesn’t balk at spinning a fresh story out of whole cloth for “new builds with imagined histories.” Fortunately, the Myles Standish offered more than a blank slate with which to work.

Built in 1871 in Duxbury, Massachusetts, on Boston’s South Shore, The Myles Standish Hotel began as a sprawling, boxy wood-frame seaside summer resort typical of the time and area. A broad, bay-facing porch fronted two stories of beadboard-swathed rooms surrounding a three-story, Mansard-roofed center. Though recasting such a pile into a home may sound like a reach, the scale becomes less daunting when we learn that, after a 1908 fire gutted outbuildings, the Mansard section was razed to leave just two wings—one later relocated—thereby reducing the Myles Standish to a half-hotel.

Armed with this background, Ahearn’s script for the property imagined a new carriage house and boat house, along with a new porch and details, to conjure up an inn, added onto over time, that survived to this day. Integrating regional materials, such as clapboards, fieldstone, and cedar shingles, and drawing on existing roof and window details, are other tactics that help put the conceit over. Even so, half a hotel is not a house and Ahearn and his clients get a pass for not attempting a literal rehabilitation of a structure originally commercial and now largely gone.

It’s a tricky balancing act to pull off. On the one hand, historical purists have long sniffed at restoring or backdating with details that never existed. For example, in the 1980s, the practice of decking out a plain-Jane building with Victorian gingerbread was often derided as “tarting up.” On the other hand, today, most acknowledge that lack of any documentation for what, say, a kitchen or addition once looked like does provide some license for a historically sensitive version of what could have been there. (My own preference is to let history be a guide. Especially for additions, traditional patterns are not only time-tested for practicality but also look more like they’ve always been there.)

Were this a more in-depth volume than a slim, graphically driven monograph stressing concepts like “reinvention,” “reinterpretation,” and “reimagining,” it would have been interesting to learn a bit about solutions Ahearn devised for practical issues like windows, roofing, and adding mechanicals. The section on moving the wing to rebuild its foundation is just this kind of thing. As it is, History Reinterpreted is an insightful lesson in the skilled, complex design choices that brought new purpose to a historic relic—something we could use more of in our day of overnight, extreme makeovers. TB

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.