Profiles

Chicago Style: HBRA Architects

Veteran firm HBRA Architects continues to fuse traditional design with the modern world.

On March 23rd, 2013, Thomas H. Beeby became the 11th recipient of the Richard H. Driehaus Prize. The award, established by the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture in 2003, honors lifetime contributions to traditional, Classical and sustainable architecture and urbanism in the modern world. According to the current dean, Michael Lykoudis, Beeby was an obvious choice. "Tom Beeby has had a transformational role in modern architecture's return to Classical and traditional design principles," he said. "Beeby's recent design of the Tuscaloosa Courthouse is a great example of how the rigor and richness of Classicism can be used to achieve a sense of place and purpose that will be relevant well into the future."

Among the many hats worn by Beeby over the years are member of the "Chicago Seven," a group of architects who challenged the architectural orthodoxy of the late seventies; dean of the Yale School of Architecture; and founding principal, design director and now chairman emeritus of Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge (HBRA) Architects. The firm was founded in 1961 by James Wright Hammond, formerly of Skidmore Owings and Merrill, on the principle that close collaboration with clients through all phases of design and construction produced the finest buildings.

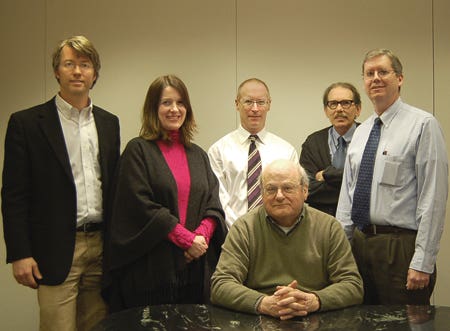

Beeby joined Hammond in 1971, followed by partners Dennis Rupert and Gary Ainge. Hammond passed away in 1986, but the firm's personal approach has continued to develop under the leadership of Beeby, Rupert and Ainge, as well as Aric Lasher, AIA, director of design, and principals Craig Brandt, AIA, and Michele Silvetti-Schmitt, AIA.

From its offices in Chicago, HBRA has designed an array of new, renovation and master-planning projects for a range of purposes and scales. The firm's portfolio spans cultural, academic, religious and government buildings, from the Palladio Award-winning Tuscaloosa Federal Building and Courthouse in Alabama, to the Baker Institute at Rice University in Houston, TX, and the Bass Library at Yale University in New Haven, CT. Prominent Chicago projects include the Art Institute's Rice Building, the Harold Washington Library Center and the Fourth Presbyterian Church's addition and renovation (1995).

Among HBRA's many professional recognitions are the Louis Sullivan Award for Architecture (1989); seven National Honor Awards from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) – its highest honor; more than 20 awards from the AIA's Chicago chapter, including Firm of the Year in 1994; and last year's Arthur Ross Award for excellence in the Classical tradition (see Traditional Building, April 2012).

Few recent projects match the logistical difficulty of the Tuscaloosa Federal Building and Courthouse. Commissioned by the General Services Administration, the 127,000-sq.ft., two-story building houses two federal courtrooms, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court, the U.S. Bankruptcy Clerk, the U.S. Bankruptcy Administration, the U.S. Attorney, the U.S. Marshal Services, the FBI, a U.S. Senator and a U.S. Representative. HBRA drew upon Classical Greek precedents to accommodate the program comfortably, and to convey a respectful presence for the federal agencies that it houses.

The building comprises a large center portion flanked by two smaller side wings, connected by stair halls. A central pedimented hexastyle Doric portico establishes the prominence of the main entrance, while the smaller wings feature Doric pilasters.

"The owner, architect and contractor team worked well together, which was necessary to complete a building like this," says Craig Brandt, AIA, principal and project architect. "Our perception is that this community considers the building's architecture and integrated art a success. This success reinforces the notion that public buildings influenced by Classical ideas can be built on time, and on budget, and that they have sensibilities that are not only useful and relevant to the building's purpose, such as its legibility, but engage the community's spirit in a way that reinforces that purpose through its expression of strength, order and dignity."

At Rice University, HBRA was called upon not only to design a formal building for the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, but also to unify the increasingly disparate campus with a new quadrangle. The 285-acre campus is home to approximately 50 buildings and more than 4,000 trees and is demarcated by five streets; Greenbriar Street, Rice Boulevard, Sunset Boulevard, Main Street and University Boulevard.

On the wishes of the university's first president, Edgar Odell Lovett, its early buildings by Ralph Adams Cram are mainly Byzantine in style, constructed of sand- and pink-colored brick, with many arches and columns. Later buildings strayed from these themes, however, with Brutalist and Mediterranean influences that obscured the character of the campus as a whole.

The new building houses both the Baker Institute and the School of Social Sciences and was conceived as a square plan with a clerestory-lit central commons. HBRA emphasized the historic tradition of the campus with a new plaza that is landscaped, along with an adjoining quadrangle to the west, to form a series of outdoor rooms and a clear pedestrian corridor to Alice Pratt Brown Hall. As settings for informal discussions and structured programs, the central commons supports the function of the main building and acts as a gateway to the west quad.

The campus's iconic Lovett Hall, designed by Ralph Adams Cram, provided inspiration for the new building's façade and centralized organization. It is monumental yet humanly scaled with arched windows and door surrounds, stone banding, columns, pilasters and recessed panels. Flemish bond brickwork with thick bed joints provides texture for the building's thematic glazed tiles and inscriptions, whose birds, fish, crosses and stars relate to Rice University, the state of Texas, and individual departments.

Inside, simple materials like wood, stone, plaster and tile are offset by ornamental mosaic floor paneling, stained concrete and dark-wood trim. To promote the campus' mission, advanced audiovisual and broadcast communication systems link the institute with an international audience. On a local scale, the second-level faculty and fellow offices are arranged to promote maximum interaction and overlook the commons via lounges and loggias.

Closer to home, HBRA was commissioned in 1984 to design a $23-million, 128,000-sq.ft. addition to the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC). Funded by the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Foundation, the wing provides exhibition and storage facilities for four curatorial departments, and preceded the 2009 addition of Renzo Piano's Modern Wing – the largest expansion in the museum's history.

The Rice Building is one of many Chicago facilities to benefit from the late philanthropists' fund, among them the Chicago Botanic Garden, the Chicago History Museum, the Children's Home and Aid Society of Illinois, Brookfield Zoo, the Field Museum, the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, the John G. Shedd Aquarium and the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

Boston, MA, firm Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge designed the main building in the Beaux Arts style for the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. It was the third home for the Art Institute, which previously occupied properties on Dearborn Street and the corner of Michigan and Van Buren Avenues. At the time of construction, the museum possessed the largest special exhibition space of any art museum in the country, and its current collection of 260,000 works of art spans more than 5,000 years of artistic expression from all corners of the world.

The Rice – or south – building bucked the trend for contemporary museum additions by remaining true, but architecturally subservient, to the original. Its gray limestone façade does not upstage the facility's main entrance on Michigan Avenue, and in keeping with preservation laws, it does not exceed the height of the original three-story building.

Much of the addition's Beaux Arts architectural detail is found on the interior, which is dominated by a two-level, daylit sculpture court and a 19,330-sq.ft. special exhibitions area, Regenstein Hall. Classical detailing and fluted columns reference the main building and reinforce the notion that the addition completes, rather than alters, the design. "The Rice wing was received favorably by the Institute for its role in making the building a coherent whole," says Beeby.

With the Harold Washington Library Center on State Street, HBRA set a precedent for the planning and design of major public libraries and left an indelible footprint on Chicago's cultural landscape. At ten stories and 760,000 sq.ft., the Neoclassical facility for the Chicago Public Library was the largest design/build project ever undertaken at the time of its construction and, upon opening in 1991, entered the Guinness Book of Records as the largest public library building in the world. In 2007, it ranked 85th in an AIA national poll of the public's favorite examples of American architecture.

The library's red granite exterior is punctuated on three sides by five-story-tall arched windows. Cast-stone medallions, corn stalks, representations of Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture, and the state motto, Urbs in Horto ("City in a Garden") by sculptor Ray Kaskey ornament the exterior.

In 1993, monumentally-scaled ornaments of Classical derivation by sculptor Kent Bloomer were added to each of the four roof corners. These include seed pods, barn owls and the Great Horned Owl, which presides over the State Street entrance to symbolize knowledge. Inside, a mosaic mural by Jacob Lawrence on the lobby's north wall depicts the life and accomplishments of the library's namesake, the late mayor Harold Washington.

"The Library alludes to great buildings of its history and surroundings, which suggest that it is part of a lineage of public buildings that belong to the city," says Beeby. "The building's monumental form, composition and symbolic expression are cultural statements that represent the notion of a public building that people in Chicago can understand."

After more than half a century, HBRA continues to fuse the sophistication of a large firm with responsiveness and sensitivity to individual client needs. The firm is currently at work on projects ranging from large-scale institutional and academic buildings to single family residences, planning studies, renovations and additions.

"We find that there is much to be learned from examples that remain resonant and successful over time, and we're particularly interested in finding where traditional principles of design and modern circumstances and building practices coincide," says Aric Lasher. "Tom evolved a critical approach and methodology in our office that has allowed us to address all manner of challenges with resilience and freedom from preconceived notions. When considered with regard to specific places and cultures, this perspective has allowed us to participate in the ongoing dialogue that drives the evolution of our cities and institutions in a meaningful way."