Profiles

Single Minded: Franck & Lohsen

Teaming up on a proposal for Lincoln Center in New York prompted friends Franck and Lohsen to launch their partnership.

By Gordon Bock

Partnerships are far from rare in the history of the architectural profession. Where many are built on different but complementary talents – think engineer-businessman Dankmar Adler and design visionary Louis Sullivan – less common are teams who collaborate on the smallest details and design as if with a single mind. That’s just the case, however, with Franck & Lohsen of Washington, DC, who have turned some of the typical practice paradigms inside-out by working closely together on every commission and making a specialty of a diverse project list.

Starting at the Center

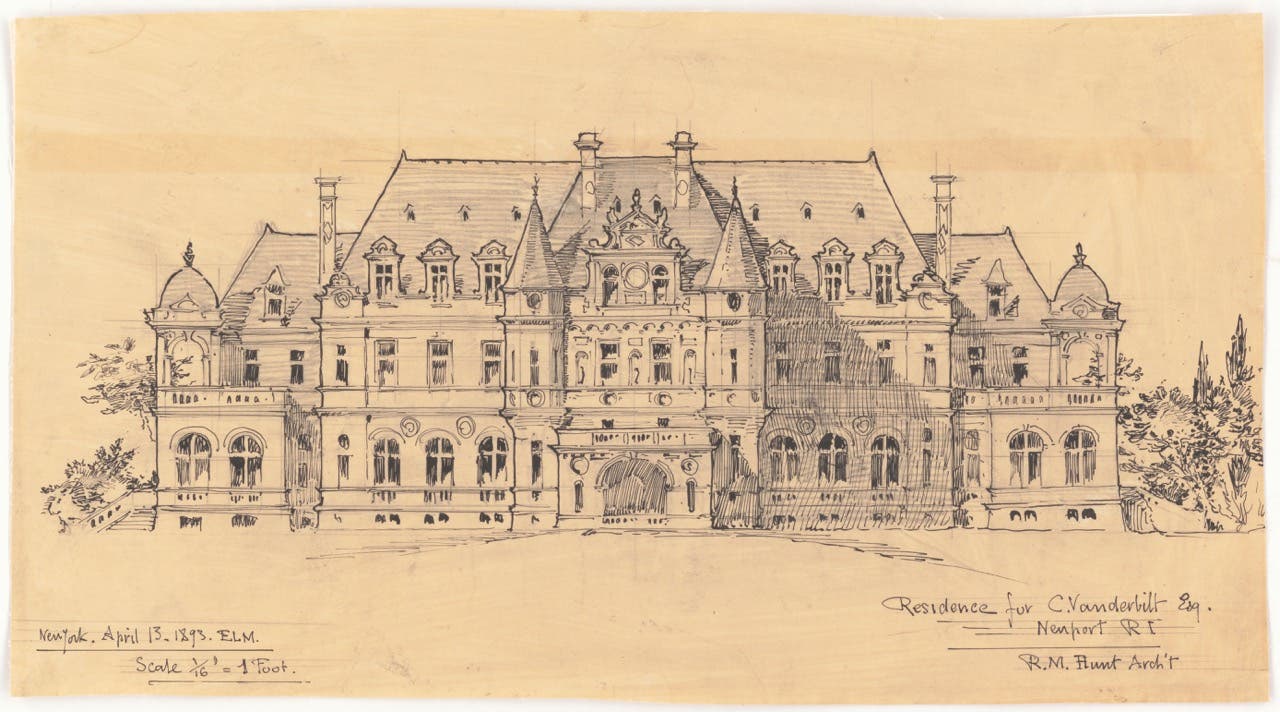

Remodeling projects have spawned many a firm, but few have the luck – or better yet pluck – to come together on a building of national notoriety. As Michael M. Franck, AIA, recalls, he was working in New York around 1999 when Art C. Lohsen, AIA, LEED AP, with whom he had worked in the office of Allan Greenberg Architect, got in touch. “Art came across an article in the think-tank policy quarterly City Journal discussing the money that was going to be spent remaking Lincoln Center in New York,” recalls Franck, “so he asked then editor Myron Magnet, ‘What if we came up with a design for what Lincoln Center could look like if they spent a billion dollars?’”

Franck audibly smirks at the “rather ambitious” reach of their suggestion, as well as the jaw-dropping budget being projected at the time. Nonetheless, Magnet gamely took the friends up on their offer and they were off and running putting together a counter-proposal with the help of some colleagues. “It was sort of a short, theoretical, What if? design charette exercise,” says Lohsen, “We spent two weeks on the proposal, but it was interesting to collaborate closely on a very tight deadline with the two of us in different cities, sending files back and forth, and using email.”

City Journal wound up publishing the friends’ efforts – even putting the design on the cover and presenting it at a press conference at the University Club in New York. “They called it ‘A New Lincoln Center,’ but then we had to come up with a name for who we were,” says Lohsen. After Franck presented the drawing to the world’s press, the friends asked each other, Well, are we in business or not? “It was a rather funny way to launch our careers and a firm,” recalls Franck but, as Lohsen adds, “We worked well together, and we were young and entrepreneurial enough to give it a shot.”

Despite the firm’s seat-of-the-pants inception, from the outset Franck and Lohsen had a crystal-clear view of their interests and objectives, as well as how to fulfill them. Recalls Lohsen, “Michael and I both came out of school in the middle of the 1991 recession, when no one was hiring architects or building terribly much, and we saw what it was like to find a job and to succeed in that market. So when we started the firm, we knew that, in order to survive as a business, we had to be diverse.” Franck adds, “By having a stake in residential, ecclesiastical, commercial, town planning, government work and international work, we’re better able to ride out the bumps in the market.”

Both partners note that that strategy has indeed paid off in recent years. “If all you were doing was one narrow market in the 2001 dip, or in 2008 when the bottom fell out, and that market disappeared, you were out of luck,” explains Lohsen. “Even if you could do other types of projects, you’d be in line behind 38 other firms that specialize in that type of project.” Franck adds, “In recent years, our residential took a dip, but our government projects went up and our church projects went up, so we’ve been able to maintain a pretty steady body of work.”

The firm’s view of Classicism is not dogmatic

The partners say they view themselves more as traditionalists, with the goal of creating timeless architecture – they do take to heart Classicism’s fundamental view that whatever you’re doing, you’re doing it within a context. “We make sure that an individual building, regardless of the project, is not just a successful building, but also a successful addition to a larger context,” the partners explain. “Everything we’ve done has always looked like it’s always been there.”

A good example of this challenge is St. John the Apostle Roman Catholic Church, an 1,100-seat house of worship in Leesburg, VA, finished about a year ago. “The church is on the edge of the historic district in Leesburg,” says Franck, “so you can imagine the hurdles we had to leap to get a large, brand-new building like this done.”

Picking up on a contextual cue, one of the firm’s design solutions was to clad the church in red brick that matches the historic downtown district. “Based upon our design and our experience working in historic districts,” he adds, “I think we were able to pull off a pretty significant new building for Leesburg that fits in quite nicely with the fabric of the city, and also within its architectural character.”

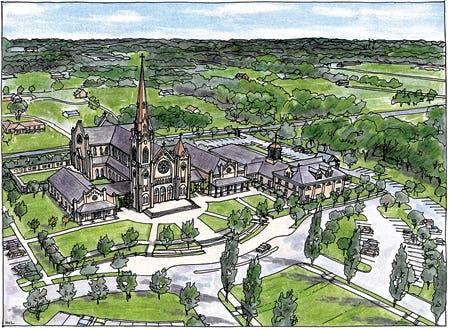

Sometimes working within a context means helping to reinforce one that was there and has been lost, or is still there but people don’t understand. The Leesburg church helped lead the firm to working on St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church, a comparable-size project in Stillwater, OK.

Here they have designed a master plan for the 20-acre site that includes a new 850-seat church and a large parish hall as well as a Christian education wing, administrative offices and a youth center. Part of the project is to study and combine two existing facilities at a new location. “It’s basically bringing two established parishes together to form a new, bigger church,” says Franck.

In a similar way, the firm has been working with Christ Church in Raleigh, NC, to help tie together offices, circulation and ancillary spaces in-between some historic buildings. “Over the years, this fantastic National Register Episcopal church has grown into a kind of hodgepodge of hallways and small spaces that don’t make much sense,” says Lohsen. “So we’re working with them on a master plan to reorganize and reorient those buildings while making some additions and improvements.”

On a smaller scale, Franck and Lohsen say that working within a context is also what they do on a renovation – particularly on renovations of significant historic buildings. “We probably do an equal mix of renovations and new work,” explains Lohsen, who notes that they are involved with projects as far afield as Brisbane, Australia, where they are assisting the Bishop with improvements to his cathedral. “They have a rather Brutalist addition on the rear of their beautiful, Gothic cathedral, and we’re looking at removing that addition and replacing it with something more in keeping with the historic style of the church. So it’s fun to be able to go in there and fix a lot that was kind of mucked up over time.”

A hemisphere away in Rome, the firm faced an historic structure context of a different ilk: a 1,000-year-old palazzo complex for the Order of Malta, a Roman Catholic lay religious order. “Over the years, this palazzo complex had grown to the point that the manager of one office might be over here, but the actual staff was over there, and there was a lack of fire stairs, ADA-type bathrooms, and other life safety systems and conveniences.” says Lohsen. “So when they asked us to come in and clean that up, the challenge was how to reorganize the spaces in such a way that it reinforces how the palazzo was originally designed.”

One conundrum was how best to add an elevator. As the architects explain, a proposal that was seriously considered – and echoes the issues in many American historic public buildings – was simply to plant a glass elevator shaft in the palazzo courtyard and let it be evident as clearly a later addition. “For us though, that’s not a very timeless approach,” explains Lohsen, “because it’s saying that, after generations, this beautifully designed courtyard doesn’t work anymore. The real answer is to do something within the fabric of the palazzo.”

What the architects were able to do is to use the elevator, and some of the development around it, to reinforce the original idea of the salons and lobbies on each level of the courtyard that had been invaded in modern times by offices. “As Classicists,” Lohsen adds, “we looked at adding an elevator not just as an elevator project – make it work and we’re done – but to ask what is the elevator doing for this room, how do people travel from the elevator to the room down the hall, and why is the whole building better because it has this elevator? It’s an opportunity to make improvements to the building to clarify the original design and intent, and sometimes pull back some of the unfortunate mess that most historic buildings accumulate over the years.”

Context on the Campus

Contrary as it might seem, ecclesiastical commissions have been something of an entrée for the firm to lay projects. “Having a successful track record behind us in church buildings has given us more of a body of work that we can demonstrate as being large, institutional-type projects,” says Franck. He notes that they have done additions and renovations to higher-education buildings, such as the contextual addition to historic Davis Hall at the University of Arkansas. It serves as a model for enhancing the traditional character of other buildings on the campus. “Hopefully, we’ll be starting a dorm project with Campion College,” says Lohsen, “which is a Catholic liberal arts college near Sydney, Australia.”

The architects note that in a market still entrenched with Modernism, traditional design is not an automatic sell, but there are enlightened exceptions. For example, Franck and Lohsen are working as design consultants for a major project underway at Longwood University in Farmville, VA: an 80,000-sq.ft. new building called University Center.

“The new president thought that the style of the building should be more in keeping with the established character at Longwood,” recalls Franck, “so he brought us in to team up with Perkins & Will, a global architecture company, to basically redesign the building to fit in more contextually with the campus.” Their first task he says was to understand what the more important buildings on the campus look like and learn from them, “not just to replicate, but to be inventive within that context, because this new University Center is a vast, vast building.”

The architects have also turned their traditional touch to libraries, such as the Washington, DC, Public Library at Petworth. Built in the Georgian Revival style in an unmistakable nod to Colonial Williamsburg, the 1930s building saw a major restoration of both interiors and exteriors that sensitively incorporated new building systems while carefully retaining historic details – even adding new, never-used details from the original design.

If you carry the notion of context to its logical extensions that could easily lead to the planning of town and civic spaces – both areas in which the architects have an active interest. For example, they are involved with Walnut Grove, a new, 60-acre Traditional Neighborhood Development in Lake Charles, LA, with its own town center.

“We’ve also been asked to help with the redesign of Barney Circle in Washington, DC,” says Franck, a problematic traffic area on the western bank of the Anacostia River that he had been interested in since his master’s thesis. “What we proposed for the South Capitol Street Project, currently under construction, is an elongated elliptical circle that makes a transition from a major avenue to a new bridge crossing the river, cleaning up a very congested area and improving the arrival to the city.” “One thing that distinguishes both of us as architects is that we are not afraid to dive in and do theoretical projects that convey some of our ideas,” Franck adds. Indeed, it’s not hard to see how that interest springs from the same context as redesigning Lincoln Center.

Gordon Bock is co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com) and lists his 2014 keynote speeches, seminars and workshops at www.gordonbock.com.