Features

Book Review: Early American Masonry

By Harley J. McKee, FAIA; new forward by John G. Waite, FAIA, John G. Waite Associates, Architects

Second Edition published by The Association for Preservation Technology International (APTI), 2017; $34.50; Originally published by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Columbia University, 1973

Paperback; 94 pages; Numerous photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9986347-0-8

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Let me begin by saying that this publication is an absolute treasure that should be on the shelf of and accessible to all professionals working in contemporary traditional architecture, design and building, those working in historic preservation and especially being of particular and inestimable value to those traditional craftsmen working in masonry or what is otherwise called the “trowel trades.”

This is a book about traditional architectural technology. You will find virtually no commentary about aesthetics or formal design. Neither will you encounter much reference to historical context or social influences. Introduction to Early American Masonry maintains a laser beam focus on pre-Civil War, circa 1860 traditional American craftsmen working in masonry from production of raw materials to methods of application.

The author, Professor Harley J. McKee, well known for his field documentation methodology and supervision of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), was a highly respected architect having studied in the U.S. and abroad at the University of Paris as well as having been classically trained at the Beaux Arts Institute of Design in New York. He was renown for his practical know-how and exhaustive knowledge of methods of traditional craftsmanship, particularly in the fields of slate roofing and masonry.

The Association for Preservation Technology International, of which the author was a co-founder and president, has after more than 40 years taken the initiative to republish Introduction to Early American Masonry, which had been long out of print and largely forgotten. Let’s take a few moments to consider the circumstances of its original publication and why this book remains so relevant today.

Mid-Century Historic Preservation

While the architectural avant garde was going gaga over the possibilities of mass produced concrete, glass and steel, the mid-century also had its fair share of practitioners and academics who were justly concerned with what was being deliberately discarded, literally bulldozed in the industrial stampede of all things Modernist. These concerns found resonance with the public leading to political support culminating in the National Historic Preservation Act of 1967.

One of the first orders of business was to commission a report on the state of both professional and public education in historic preservation with a notable emphasis on “Restoration” that is to say, traditional building craft skills.

The Whitehill Report on Professional and Public Education for Historic Preservation acknowledged that as of 1967 there were no known “centers for the traditional building crafts within the United States.” Below is one of the findings under the heading “Conservation of the Traditional Building Crafts”:

“Written and illustrated publications describing early craft methods and techniques. A few publications of this kind are available, though scarce. However, a vast body of essential knowledge is available in the minds and notes of specialists. A systematic program should be developed to get this information written down and duplicated for general use.”

The report continues, “Publications on various levels are essential to both professional and public education. On the professional level they are necessary both for the training of architects and craftsmen.”

The following year, 1968, the Graduate Program in Restoration and Preservation of Historic Architecture at Colombia University initiated a new course in early American building where Professor McKee developed a lecture series covering early American masonry. By 1973, Columbia University and The National Trust for Historic Preservation jointly published the subject of this review, Professor McKee’s Introduction to Early American Masonry, as the first (and unfortunately only) in a planned series on the technology of early American building.

A Peek Inside the Treasure Chest

One of the first things that struck me was the precision in terminology exercised by the author. He makes a point of immediately establishing a vocabulary, highlighting American uses of important terms for materials and methods, noting occasional differences in usage or vocabulary between America and England.

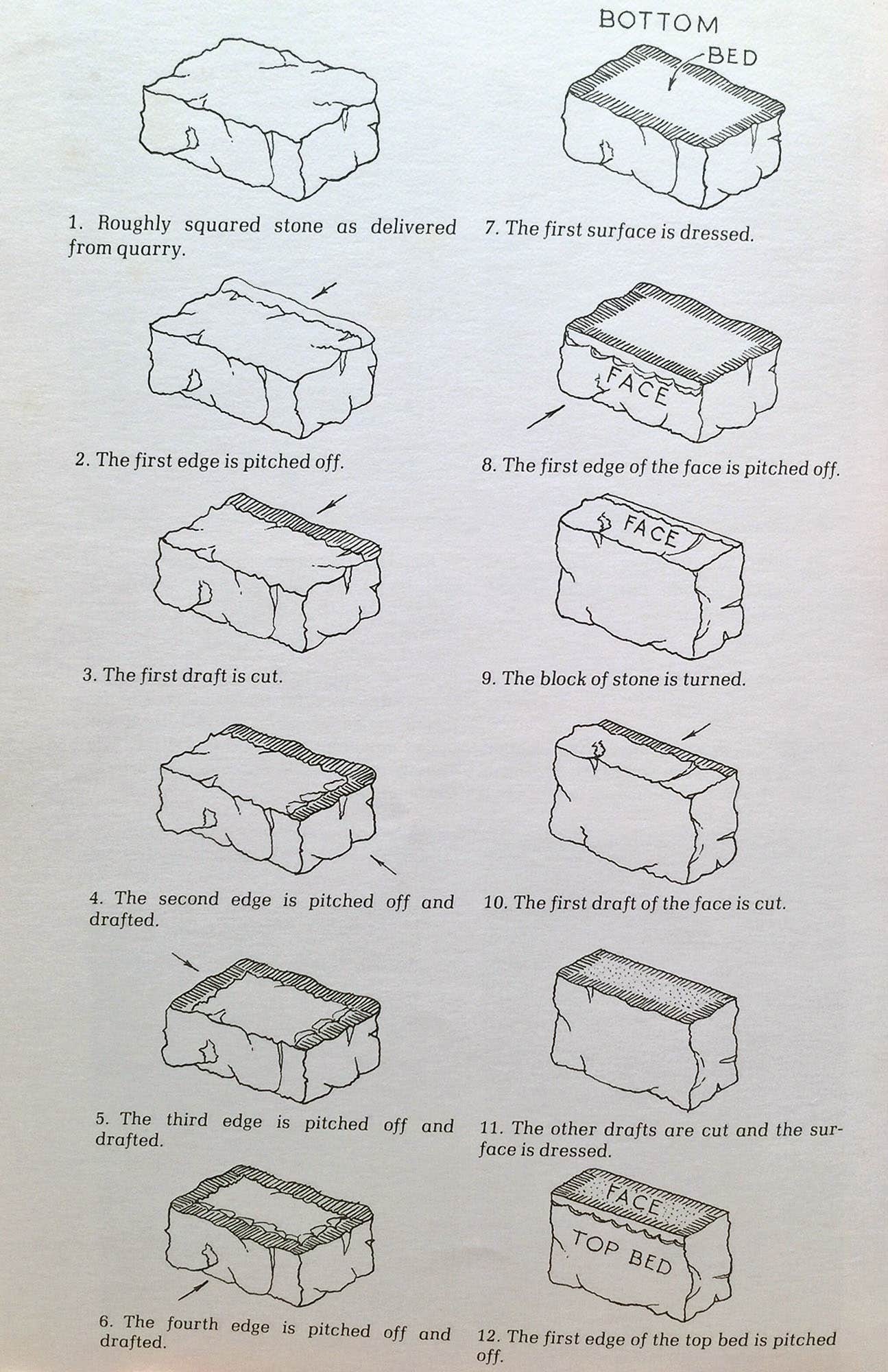

Approximately two thirds of the book is devoted to traditional craft methods, the remaining third to materials. Stone is given slightly more attention than brick masonry and plaster. This is understandable as the quarrying and carving of stone is considered, in addition to the masonry. Having personal experience in plaster, stone and brick masonry, I can testify that the information presented is quite accurate and well presented, enriched by the many hand drawn illustrations by the author himself.

Quite unique is the identification of numerous historic American quarries for sandstone, limestone, granite and marble. In addition to hand drawings, the book is replete with photos highlighting exceptional examples of craftsmanship from around the country. The book concludes with an Appendix that points to a number of valuable 19th- to early 20th-century sources for further study.

Superbly researched yet presented in a manner easily accessible to students and laymen alike, I would recommend Introduction to Early American Masonry as a mature work built on a lifetime of teaching, documentation and the practical hands on experience of historic preservation.

To order a copy of Introduction to Early American Masonry: Stone, Brick, Mortar and Plaster, go to: www.apti.org.

My name is Patrick Webb, I’m a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of natural, historically utilized plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime in contemporary architectural specification.

I was raised by a father in an Arts & Crafts tradition. Patrick Sr. learned the “decorative” arts of painting, plastering and wall covering as a young man in England. Raising me equated to teaching through working. All of life’s important lessons were considered ones that could be learned from the mediums of tradition and craft. I found myself most drawn to plastering as I considered it the richest of the three aforementioned trades for artistic expression.

This strong paternal influence was tempered by my grandmother, Geraldine Webb, a cultured, traveled, well-educated woman, fluent in several languages. She made a point of instructing her young grandson in Spanish, French, formal etiquette and opened up an entire worldview of history and culture.

After three years attending the University of Texas’ civil engineering program with a focus on mineral compositions, I departed, taking a vow of poverty, living as a religious aesthetic for a period of seven years. This time was devoted to clear reasoning, linguistic studies, examination of world religions, exploration of ethics and aesthetics. It acted as a circuitous path leading back to traditional craft, now imbued with a deeper understanding of interconnection in time and place. I ceased to see craft as simply work or labor for daily bread but among the sacred outward expressions of the divine anifest

within us.

From that time going forward there have been numerous interesting experiences. Among them study of plastering traditions under true masters here in the US as well as in England, Germany, France, Italy and Morocco. Projects have included such high expressions of plasterwork as mouldings, ornament, buon fresco, stuc pierre, sgraffito and tadelakt.

I’ve been privileged to teach for the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, SC, where I currently reside and for the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art across the US. “Sharing is caring” – such a corny cliché but so true. I hardly know a

thing that hasn’t been practically served to me on a platter. I’m grateful first of all, but now that I might actually know a few things, it becomes my responsibility to be generous as well.