Features

Discriminate Expectations

Today, the sight of an elegant Roman Classical pedestal bearing a heroic figure on horseback, or a triumphal arch in full regalia, provokes in some a sense of suspicion rather than one of awe and admiration. Traditional monuments have suddenly and increasingly found themselves as foreigners in their homeland. This suggests a changing landscape for traditional monuments and the notion of commemorating.

In the past couple of years, the United States has experienced a crescendo of discourse and action related to past monuments and social justice. As the majority of these monuments are traditional, the narrative of discriminatory aesthetics has come to the doorstep of the traditional design community. While perhaps not invited, it is nonetheless here and offers an opportunity for several discussions: answering questions about the nature of traditional monument design; claims of being unjust; critical reflection; and ultimately, solutions for how best to proceed.

Traditional monuments are just useless antiquated attractive objects.

Monuments are valuable assets of our built environment, providing a mechanism to come together with others to capture and share values. Though designed in a set time and place, they are situated in the living fabric of the community that grows and evolves around them. They act reflectively over time to embed identity and to educate us about the world, and they can encourage us regularly to overcome mundanity and be better versions of ourselves for and with others. They are not merely statements of power or vessels of strict historicism but rather transcendent interpretations of memories that can speak rhetorically about “truths” that are liberated from reality.

Traditional monuments are particularly well equipped to deliver on this value, as commemoration is congruent with the idea of passing on from culture to culture through a shared timeless language. The aesthetics of traditional monuments are based on authentic principles that render humanistic, recognizable, ordered, beautiful, and meaningful works of civic art that bring delight to civic spaces. Further, traditional monuments lend themselves to universality, in that these same principles can occur in completely different places and times, yielding a rich resultant of connectivity and difference.

Traditional monuments are symbols of oppression and racism.

Accusations about traditional and Classical architecture inherently being oppressive and racist is denying the ontological reality of architecture, which is that inanimate creations cannot harbor these qualities, despite any intended allusions by the maker. In other words, the choice of architectural aesthetic is not bound by political or cultural ideology. The claim that Classical architecture, in particular, is morally bound by the Nazi or Fascist regimes because they used this language is false, given that democracies do the same. Further, in America, heroic Classical monuments are used both by and for subjects of the Confederacy and the Union alike. When assessing traditional monuments, it is critical to use both moral and aesthetic judgement.

Traditional monuments do not represent the values of contemporary society and its needs for commemorating.

On this count, one could concede that this claim is true, though one might ask whether that is actually a good thing. The purpose of monuments seems to be shifting to reflect society’s current cultural ethos. Contemporary monuments tend toward autonomy, atomization, anti-heroic apologetics, equity, abstraction, and emotional release with a fixation on mourning and a provision of civic therapy. While these qualities may be needed to add to the idea of what monuments should be for us, this sweeping trajectory suggests an essence of counter-commemoration.

The contemporary ethos also participates in a conscious dismissal of the past with a discriminating and arrogant posture that emboldens hostility and espouses moralizing from a contemporary pulpit. “We would surely have done differently if we were in your shoes and certainly know better now.” This stigmatization extends to the traditional languages employed by monuments and explains recent overt reactions aimed at traditional monuments deemed offensive to our modern sensibilities, regardless of location or subject matter. It is healthy to understand that we are products of our own age and that it is unreasonable to expect different eras to reflect the morality of another. The continuity of traditional design inherently mediates these conflicts and differences through neutrality, timelessness, and appropriation.

Tolerance of intolerance should not be tolerated in our civic spaces.

Arguably, the greatest challenge traditional monuments face is having the cultural context within which they can exist. Calls for reimagining commemoration in civic spaces by exorcising past traditional monuments because they are thought of as being intolerant or incorrect espouse a principle of equity in attempting to purify and level the civic playing field. While correction and representation for underrepresented people is needed, this default mode causes an atomization of commemorative causes and a repudiation of the values of a traditional civic realm. Cautionary admonitions such as “the slippery slope” and “those who forget the past are destined to repeat it” come to mind.

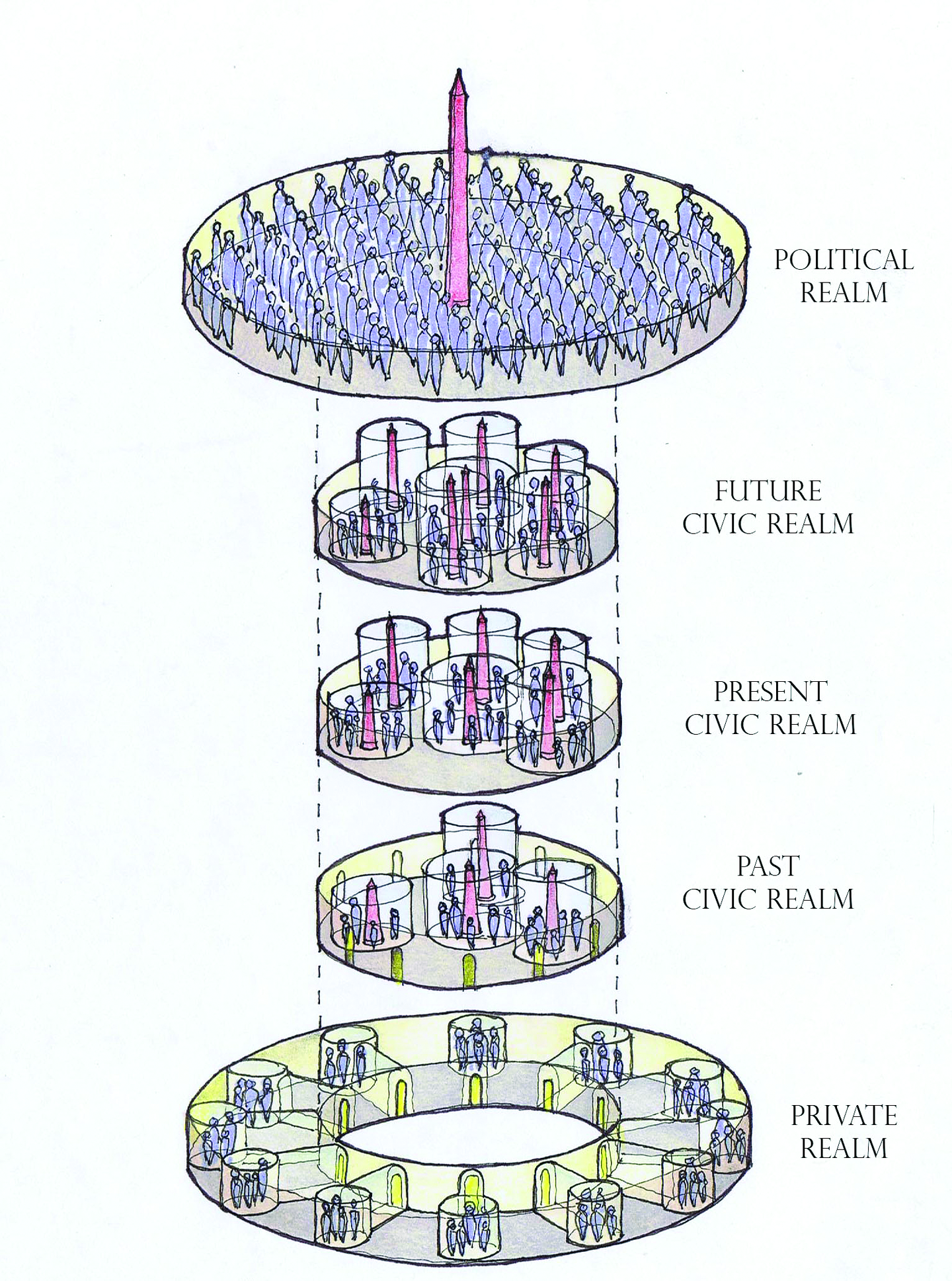

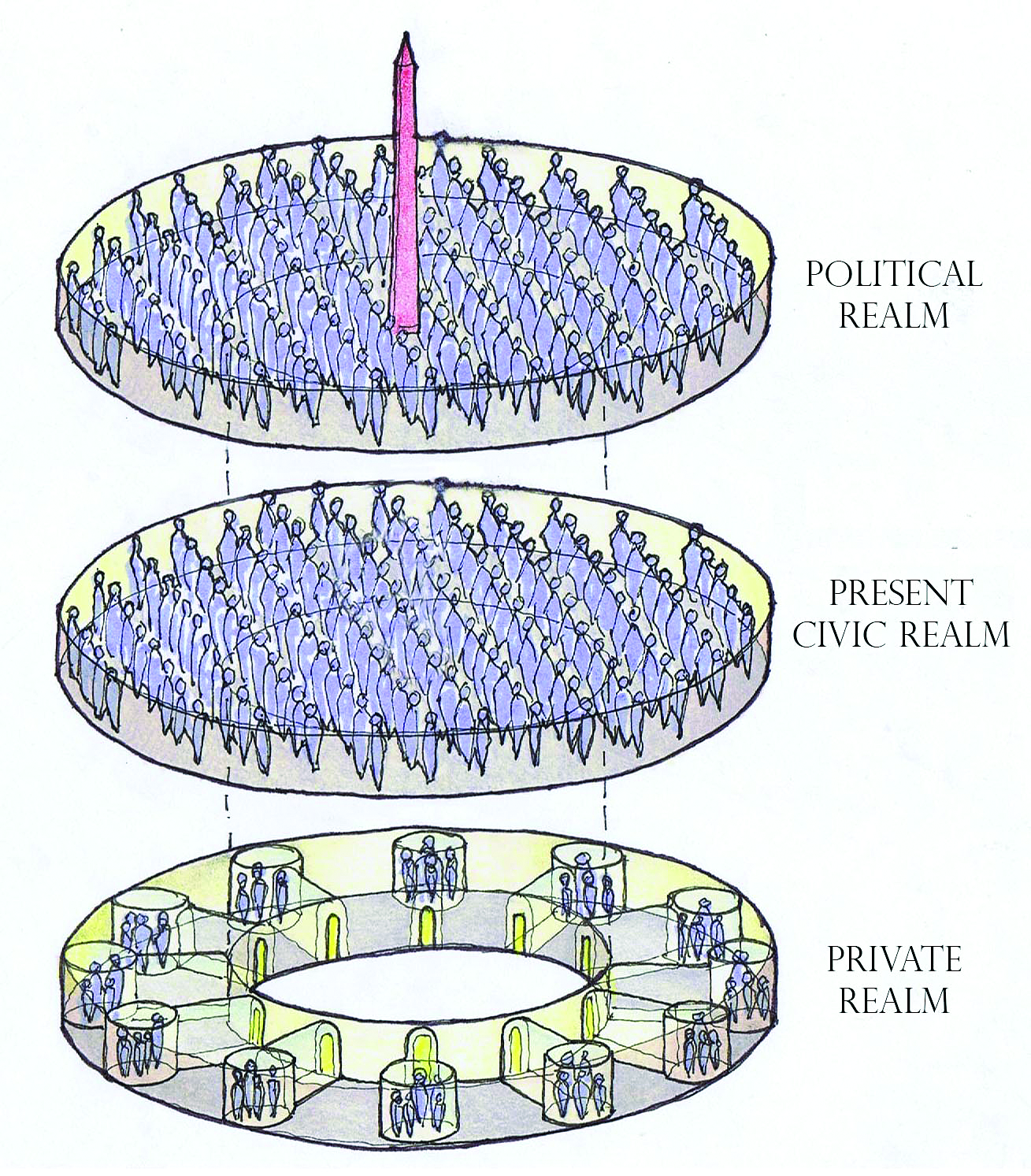

Writing more than a half century ago, political philosopher and holocaust survivor Hannah Arendt foreshadowed our current state and offers a compelling approach to help navigate these complex and sensitive waters. In her estimation, it is necessary in a traditional democracy to have three different and overlapping spheres that accommodate human affairs. Those spheres or realms are the political, the private, and in-between the two, the civic or social. The essence of the political realm is equality under law for all people, without discrimination. The private realm is exclusively for individual expression. Finally, the civic or social realm allows for distinctions or discriminating actions such as association, engagement, expression, and commemorating (Fig. 1). It is an ambiguous paradoxical realm where all things are not equal, yet there are implicit expectations of civility, commonness, and charity.

The key lesson here is about properly placed expectations and the provision for necessary human activity. When stepping out from the private to the social realm, the milieu of humanity is admitted with all its attendant complexities. This is important because it is precisely where, by free association, group diversity can happen. Further, it nurtures a habit of togetherness, past, present, and future. In this model, civil discourse is more easily achieved. Absent this expectation, one is predisposed to misreading the room.

Contemporary notions of the civic realm seem to be moving toward a blurring of the political and social realms, where the expectation of literal individual equality found in the political realm and distrust of the past replace discriminating acts, therefore compromising the healthy distinction between the essential realms. This manifestation of the social realm has a flattening effect that ironically creates resentment and intolerance and inhibits traditional commemoration (Fig. 1).

Atonement: at – one – ment.

Memory, identity, and aesthetics all have key roles to play in the primary medium for monuments. The memories that happen through commemoration help us to make sense of the world in developing a comprehensive and truthful narrative. In order for this to happen, those memories necessarily need to be curated for relevance. That is to say, sometimes forgetting/removing or correcting a memory is necessary, sometimes it is prudent, and sometimes it is an overreaction based on misplaced expectation. Whatever the realm, we can set as a worthy goal for commemorating the tenets of our nation’s founding documents. These principles would help monuments communicate the aspirational values of equality, or at least not contradict them. The cumulative effect ultimately helps us to remember the right things in the right ways to acquire a better sense of our identity and to potentially atone for wrongs in moving forward.

Traditional monuments are not just for powerful, rich white men.

Traditional monuments and a traditional civic realm hold somewhat unexpected keys to successful resolution in addressing commemorative injustice, with a particular capacity to attract and inspire with beauty and nobility. In Franklin, Tennessee, there is a new traditional statuary monument of a humble-noble United States Colored Troops soldier in juxtaposition with an overwrought-noble Confederate monument (Fig. 2). The dynamic between the two is jarring, but what is important here is the deployment of the powerful dignified image of that heroic black figure fighting for a noble cause in the same capable language as the Confederate soldier. This inclusionary act of representation brings a particular group of people together to help form a more complete and hopeful narrative, elevating issues that still need resolving within the context of the civic realm, using an architectural language that is unparalleled in its ability to please and inspire through connectivity.

For this reason, current ideas of contextualizing monuments, whether by juxtaposition or increased representation, are very compelling. Other contemporary traditional examples contribute to the increasing presence of diverse and under-represented groups that enliven the commemorative landscape, one example being a new monument honoring Women’s Rights Pioneers in New York City (Fig. 3). Contextualization allows us to remember and see the truth, and to potentially reconcile and forgive in a rich and dignified way.

How can we move forward?

The qualities of traditional monuments should not be jettisoned because of who uses them. Instead, this language, with its formal and poetic potential, should be encouraged and made more available to all people. And if differences are to be celebrated, they need to be in the same civic room with calibrated expectations. The hope, then, is to bolster broader group identity of sameness through charity and memory—a memory that resonates with the cultural depth and dimension of our nation, a nation that is young, gifted, and not flat.

C.J. HOWARD is an assistant professor at the School of Architecture and Planning, The Catholic University of America.

C.J. Howard is an Assistant Professor at The Catholic University of America where he teaches in the newly launched classical traditional architecture and urbanism track. A registered architect who has spent nearly two decades practicing in the Washington, D.C. region, and has extensive experience working for firms nationally known for their commitment to, and expertise in, classical and traditional design.

Mr. Howard has most recently been a Lead Project Architect for McCrery Architects in Washington, D.C., leading the design and construction of major ecclesiastical projects (both to benefit vibrant and growing catholic communities on university campuses as well as expanding dioceses). Some of those projects include: a new Thomas Aquinas Chapel and Blessed John Newman Student Center at the University of Nebraska (Lincoln), renovated Saint John Paul the Great Chapel at Mundelein University, a New Christ the King Chapel for Franciscan University of Steubenville and a new Sacred Heart Cathedral in Knoxville, TN.

In addition to his ecclesiastical portfolio, Mr. Howard has worked on a variety of residential and civic projects including several urban design projects in collaboration with the District Department of Transportation, to propose new visionary projects for our Nations Capitol. He has also garnered attention for his entries in design competitions including a 2008 winning entry for a Contrabands’ and Freedmen’s Cemetery Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia. His winning design, chosen from among several hundred entries submitted from 20 countries, was used as the design framework for the memorial which was completed and dedicated in 2014.

Mr. Howard received both his Bachelor of Architecture (2000) and Master of Architectural Design and Urbanism (2010) from the University of Notre Dame. In 2010, Mr. Howard received the Ferguson & Shamamian Graduate Prize for excellence in classical/traditional design exhibited in a graduate thesis. In 2019, Mr. Howard won the Leicester B. Holland Prize Competition. He is licensed in the Commonwealth of Virginia and is a member of the Institute of Classical Architecture, National Civic Art Society, and National Council of Architecture Registration Boards.