Features

City Reimagined

Today many motorists speed through Hartford, Connecticut, unaware of the capital city’s fine legacy of human-scaled architecture, where historic urban traditions once thrived. Now, as city, state, and federal transportation officials plan to rebuild Interstate Highways 91 and 84 through Hartford, and with public consensus overwhelmingly in support of repairing the mistakes both expressways imposed on the city’s physical, social, and cultural fabric, a rare opportunity is emerging to restore Hartford’s character by considering ways to revive and reinterpret the city’s geneses: American Romanticism and the City Beautiful Movement.

Led by Hartford Congressman John B. Larson in partnership with the City of Hartford, business leaders, and the non-profit iQuilt, a consortium of key cultural institutions (the latter initiated by the Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts and the Wadsworth Atheneum, America’s oldest art museum), an ambitious public works project called Hartford 400 is underway. The projected completion date, 2035, will mark the city’s quadricentennial. Applying past successes at Trinity College and the Hartford Public Schools, iQuilt members are determined to reverse the city’s decades-long endurance of crumbling dikes, obsolete road decks, and a disjointed cityscape held hostage by the automobile.

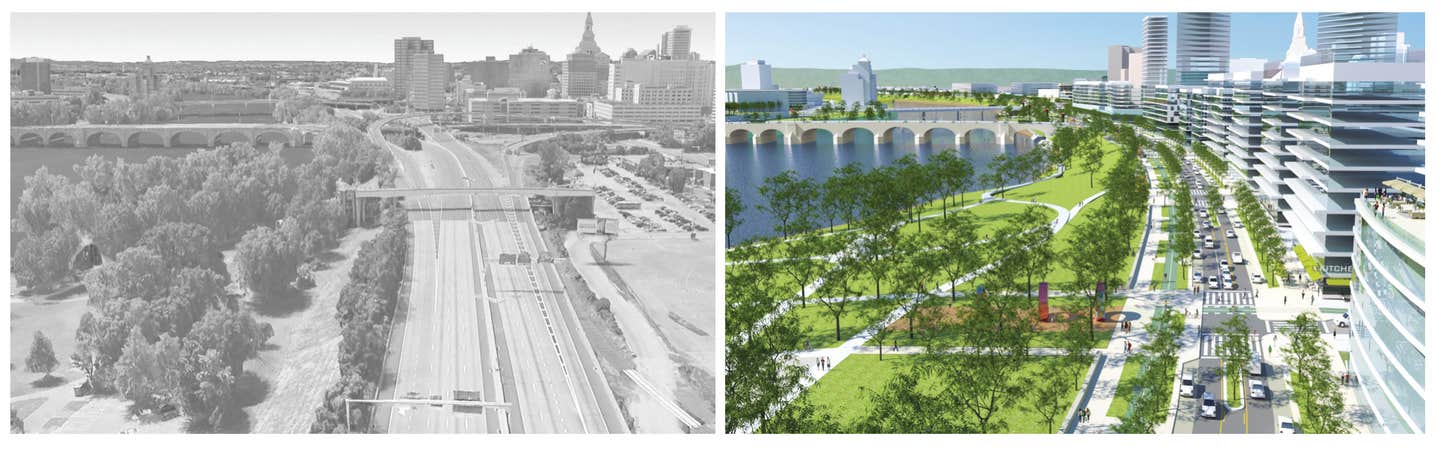

iQuilt’s Hartford 400 plan, as it is known, would liberate hundreds of acres of under-utilized, inaccessible, or environmentally compromised land from excess private motoring in exchange for a more human, pedestrian-scaled landscape worthy of investment, and where mixed-use development can thrive. Prepared under the direction of Santa Monica, California-based urban designer Doug Suisman, FAIA, the Hartford 400 plan envisions a vastly transformed capital city able to compete with the region’s overcrowded and climate change-vulnerable giants of Boston and New York. Suisman, a Hartford native, intends to liberate downtown Hartford and much of East Hartford, just across the river, by relocating major highway interchanges in or adjacent to the cores of both municipalities and by modernizing and resituating their flood-control infrastructure. Endorsed by Connecticut’s congressional delegation, including Governor Ned Lamont, and Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin, Hartford 400 emphasizes major new amenities including extensively landscaped open spaces and riverfront access. Placing people over cars and trucks is the prevailing theme.

History

Before the Civil War and into the early twentieth century, both American Romanticism and the City Beautiful Movement grew from literature, painting, sculpture, and music, guiding man’s quest to know the wilderness, and in architecture, civil engineering, and public art, reflecting his desire to control nature. As an outcome of progressive social reforms in North America, both movements were cloaked in allusions to traditional classical, medieval, and renaissance precedents, awakening America’s sense of place, so architects, engineers, artists, and journeymen builders could craft a better civilization. New York City’s Central Park, whose design balanced the then-burgeoning metropolis’ growth with verdant, accessible open space, is perhaps the nation’s highest example. Hartford’s experience was no exception.

Bushnell Park and the Machine in the Garden

Eager to tame its flood-prone rivers, Hartford’s advocates and engineers created Bushnell Park and its Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch and Bridge (1886). Their designs presented an unabashed Norman-Gothic monument with stone embankments and carriageways over a formerly polluted Park River, where tanneries and slaughterhouses once stood. The improvement was framed by Richard Upjohn Jr.’s new State Capitol (1879) and the gracious Corning Fountain (1899), an ensemble that remains resolute and picturesque to this day. Likewise, Hartford’s vast Romanesque Revival railroad station edifice (1889) and robustly corbeled Hartford Public High School—demolished in 1963 to make way for Interstate Highway 84—complemented the scene. All stood as strong precursors to the City Beautiful Movement that would soon follow.

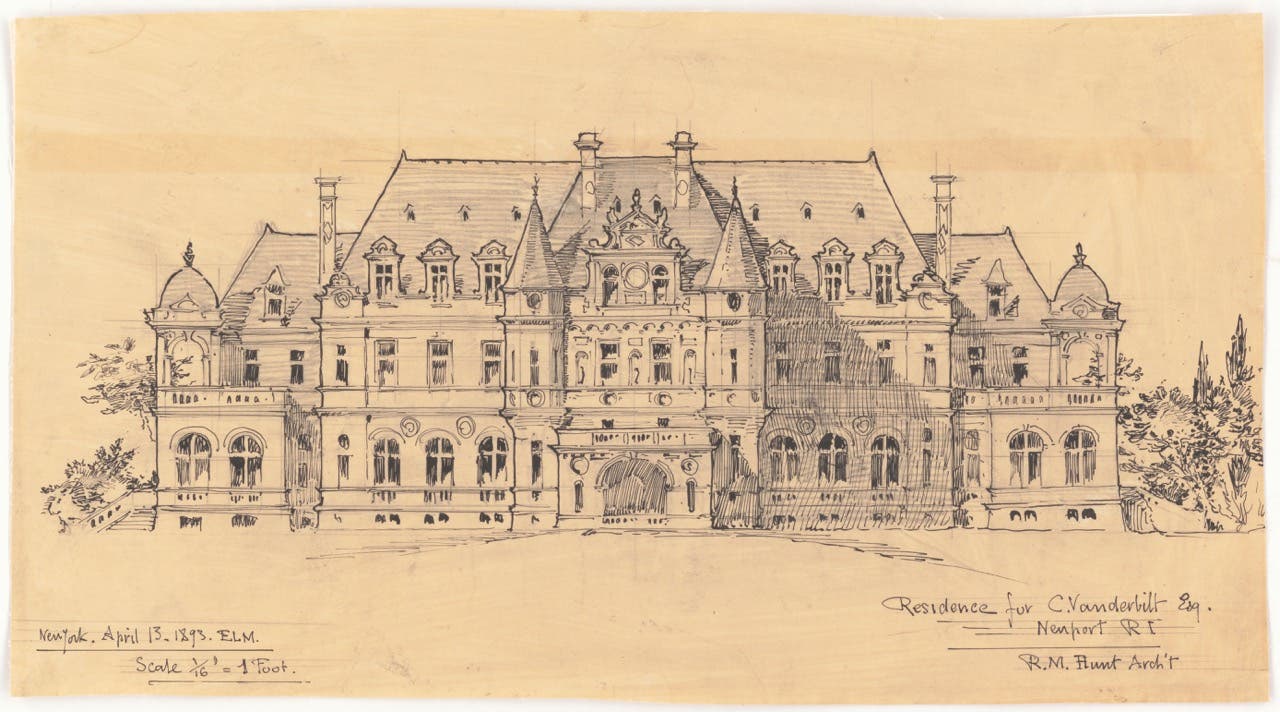

Originating with architect Daniel Burnham’s plan for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the City Beautiful Movement used the engineered landscape to leverage significant civic spaces and public buildings to recall the grandeur of Classical Europe that for many Americans symbolized the virtues of Western progress. The movement influenced emerging urban centers including Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas City, and most famously, Washington D.C., by adapting a tradition-based architecture using modern industrial methods and means. An early promoter of the City Beautiful, Hartford-bred founder of American landscape architecture Frederick Law Olmsted believed that blending and composing natural and manmade aesthetics —what some historians have referred to as the “technological sublime”—could compel order amid what was then perceived as the Young Republic’s physical and socio-economic chaos. Strong examples of Hartford’s City Beautiful engineering and architecture include Hartford City Hall, the State Library, the Bulkeley Bridge (1905), and Travelers Tower (1919). Spanning the Connecticut River when completed, the bridge was among the longest segmental stone arch bridges in North America. It was designed by a civic leadership determined to build “an ornament to the city which should endure forever.” Travelers Tower, the seventh tallest building in the world when completed, stands as a posthumous monument to the insurance giant’s Egyptologist founder, James G. Batterson.

Sadly, Hartford’s early progress toward civic beauty was short-lived after the hurricanes of 1936 and 1938 flooded the Connecticut and Park River basins, devastating downtown businesses, and compelling state contracts

to entomb the Park River and wall off the Connecticut River frontage from which the colonial-era city was born. By the late 1950s, Interstate Highway 91 would be added between the river dikes and downtown where a boulevard and walkable open space once stood, and where, no less,

the venerable Bulkeley Bridge would be compromised

by a widening program (encouraged by then-consultant,

Robert Moses) to accommodate Interstate Highway I-84. Flush with funds, state and city engineers used these catastrophes to mummify the city. Not until the late 1980s would the non-profit Riverfront Recapture organization, with public, and private donations, succeed in mitigating the obstructions caused by these onerous expressways.

Access to the area’s natural and manmade attractions

has improved, but more can be done to reconnect

the city to its riverfront.

Hartford 400: Expanding on the City’s Brand

An award-winning city-building proposal, Hartford 400’s potential sweeping makeover is a vote of confidence in the future of Connecticut’s state capital, however, in projecting its future, city and state planners must remain vigilant to ensure the plan’s outcomes transcend public works. Beyond the new open spaces and landscape-capped roadways, the plan’s renderings may imply a concept program only as powerful as the square-footage development envelope it can sponsor. Amid the impressive renderings and demographically sensitive program, does one detect a reluctance to specify an agenda for civic beauty? Will Hartford’s movers and shakers distinguish their future public realm from most other cities across North America? These questions must be mulled carefully for Hartford to reign competitive. A City Beautiful-inspired revival leveraged by the Suisman schematic could offer a successful path toward Hartford 400’s goals.

Success is in the Details

Hartford planners have the agency to include traditional precedents in their design guidelines. However, oftentimes private developers, have a preponderance to dismiss such methods as too costly, foregoing the style and scale characteristics so popular among city-dwellers and tourists by favoring profit-driven “systems” of machine-manufactured, product-driven construction. Alas, although new buildings can apply traditional methods literally, much can be done strategically to deploy traditional language, satisfy public demand, and meet challenging budgets to guard against expedient cliché outcomes. Boston’s Seaport District, where exterior metal panels, glass curtainwall, and “rain-screen” facades present pedestrians with a non-variegated, minimalist atmosphere, offers a cautionary tale. Developed after the completion of Boston’s Central Artery Tunnel Project, the area is largely leased, but its architecture—its public face—has been roundly panned as cold, repetitive, “expedient,” and undistinguished.

Hartford 400’s local, regional, and statewide stakeholders—its planners, engineers, and architects—can help cultivate an architecture that re-engages the public’s imagination by encouraging a reintroduction of traditional design and construction methods. Where there is no appeal, business goes elsewhere, so from a civic design perspective, what can be done to attract investment? Let us consider, in part, the following:

1. Reassert a ban on parking garages exposed to key pedestrian street edges as outlined in the city’s Greenberg plan of 1998. These edges destroy urban intimacy, reduce livability, and depress property values. The city should go as far as marking some garages for elimination.

2. Establish a Civic Design Commission to shepherd policies that firmly encourage developers to reference and/or reinterpret traditional design solutions of the past, particularly composed using brick and masonry cladding, limestone lintels and cornices, slate and copper work, architectural carpentry, true divided light windows, wrought-iron fixtures such as balconies and lighting, and rooftop articulations such as dormers, chimneys, and finials, as well as promoting the construction and maintenance trades behind them. Encourage scrutiny of facades proposed in prominent locations using sheet-metal or fiber-board panels. Push developers to convey durability as a discernable priority in their projects.

3. Assert a moratorium on the demolition of buildings in the city possessing the qualities listed above; Hartford has lost enough of its traditional and intimate urban fabric already. Don’t wait on the formalities of historic landmarking. Work with area NGOs and NRZs to identify architectural assets in all neighborhoods, and of all scales.

4. Encourage a critical-regionalist, craft-vernacular tradition through what New Haven architect and University of Hartford Professor Duo Dickinson, FAIA, describes as Invocative Design: “We forget that history has gravity—constant, immutable, and undeniable. Architects either pretend there is no history or, alternatively, that only history is legitimate. Humanity simultaneously loves the past and the thrill of freedom. Invocative architecture embodies both without the pandering or posturing.”

Diversity Matters: The City Beautiful

A quick summation of Hartford’s demographics reveals a primarily African and Hispanic community undergoing further diversification. Burnham had confidence that Chicago planning “would be taking a long step toward cementing together the heterogeneous elements of our population, and toward assimilating the million and a half of people who are here now but who were not here fifteen years ago.” In that spirit, and with the Federal Highway Administration acting as a catalyst, the Hartford 400 Plan can grow the city by reuniting Greater Hartfordians at its core. How ironic then, given the city’s historic, highway-driven dispersal, that were it not for the need to replace these roadways , less attention would be paid to Hartford’s city-building mission to reverse decades of anti-urban planning and development. What goes around comes around; drawing back Hartford’s suburban ex-pats is an equally noble goal.

By embracing Daniel Burnham’s “Make no small plans” edict, Hartford leaders can articulate Representative Larson’s ambitions by extending them toward a civic design agenda appropriate to locale. Addressing this challenge need not be overly prescriptive or slavish to facsimile but built upon the city’s lost and remaining Classical and Romantic antecedents in architecture and the arts, generally. Indeed, use this opportunity, for example, to embrace the legacy of Hartford native Frederick Law Olmsted by naming whatever major riverfront boulevard the project yields in his honor. Likewise, capture the story of screen legend Katharine Houghton Hepburn, whose oft-stated pride and pleasure in having grown up in Hartford —her family’s progressivism and commitment to equal rights—elevates her legacy to a status equivalent to another famous Hartfordian, Samuel Langhorne Clemens, aka Mark Twain. A recreational greenway or garden in Hepburn’s honor, with pavilions apropos, would be admired if not beloved.

It’s an exciting time to envision Hartford’s rebirth, but much of the plan hinges on state officials as a city-building initiative. Daniel Burnham’s belief that “a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die” is only as good as the underwriting it commands, and the livelihood its fabric can generate. Whether Hartford 400’s users love it enough to see it recorded for posterity, only time will reveal. TB

Michael J. Tyrrell, a native of Fairfield, Connecticut, is a former Hartford resident and University of Hartford Adjunct Faculty member.

A Boston-based Consultant in Architecture and Urban Design, he serves on the board of the New England Chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art. Michael may be reached at Onetyrrellplaza@gmail.com.