Features

Book Review: Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts

Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts

edited by Jeffrey W. Cody, Nancy S. Steinhardt, and Tony Atkin

University of Hawai‘i Press, Honolulu; 2011

407 pp; hardcover; over 200 b&w and color illustrations;

ISBN 978-0-8248-3456-2

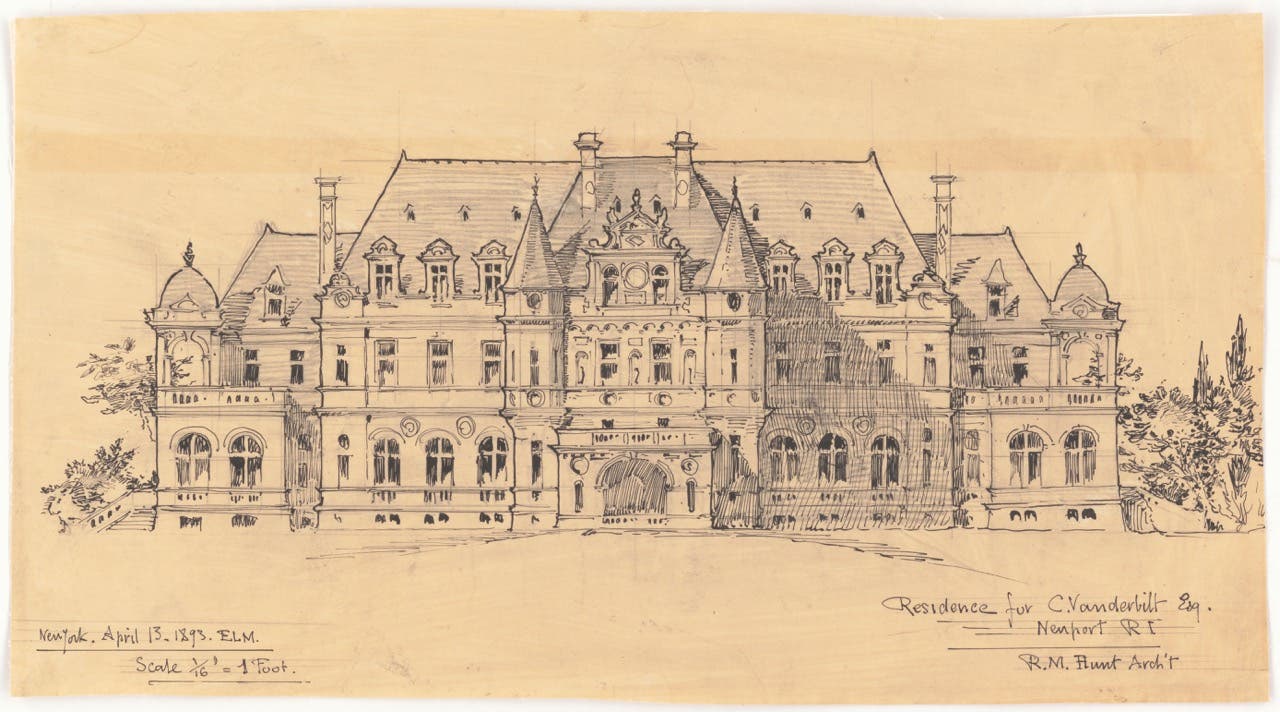

Students of the history of architectural design are familiar with the impact of France’s École des Beaux-Arts upon American architecture. Founded in the mid-17th century, the École taught architecture, painting and sculpture with a thorough grounding in Ancient Greek and Roman principles. By the late-19th century the school was attracting students internationally, including such notable American architects as Charles Follen McKim, designer of the Boston Public Library (1888-1895), and John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings, designers of the New York Public Library (1897-1911).

The American embrace of Beaux-Arts aesthetics resulted in numerous schools of architecture upholding this tradition. These institutions welcomed the influx of Chinese students in the early-20th century, who were beneficiaries of their country’s Boxer Indemnity Fund: Instead of demanding monetary reparations after the anti-foreigner riots of China’s Boxer Rebellion of 1900-1901, the U.S. had asked that China give scholarships to deserving students so they could study at American universities. Thus the United States became the main source of education in Beaux-Arts design for Chinese students of architecture from the 1910s through the 1940s.

This fascinating and under-appreciated cross-pollination of Eastern and Western architecture is thoroughly examined in an absorbing new book, Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts, edited by Jeffrey W. Cody, Nancy S. Steinhardt, and Tony Atkin. Along with contributions by the editors, this volume includes articles by a dozen authorities, Chinese and Western, who shed new light on the historical, political and artistic impact of this innovative period.

Part I

Part I, “Divergence to Convergence,” is an examination of the traditional timber-framed architecture of China, noting such fundamentals as the use of quadrilateral shapes (literal or implied) and symmetrical lay-outs, the tendency to design horizontally rather than vertically, a fondness for polychrome exteriors, and the construction of buildings as components of groups rather than individual structures.

The basics of 19th-century European Neoclassical architecture, typified by l’École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, are outlined as well. The 20th century had brought a conceptual leap to China, from construction by jiangren, or craftsmen, to the emergence of practicing architects, or jianzhushi, and a new era of design inspiration was launched.

Part II

Part II, “Convergence to Influence,” looks at the effect of the Beaux-Arts approach upon the Chinese who were studying architecture in America. It features commentaries on the influence of American urbanism and the City Beautiful Movement of the 1910s and 1920s; the nature of Chinese architectural education in the early-20th century; the adaptation of Beaux-Arts methods by Chinese socialist ideology in the 1950s; the influence of Soviet architecture on Chinese design; and the nature of architectural design and construction in Taiwan after 1949, “when many anti-Communist architectural professionals accompanied the Nationalist government in its move from the Chinese mainland to Taiwan.”

Part III

Part III, “Influence to Paradigm,” is sub-divided into three main sections. The first explores the work of Yang Tingbao, Dong Dayou and Liang Sicheng: three notable Chinese architects who studied in the U.S. and worked during China’s late Republican and early Socialist periods, a time when there was no single predominating model for architectural practice. That openness resulted in such unique Neoclassical structures as Yang’s Shenyang Railway Station (1927) in Nanjing and Dong’s Greater Shanghai Civic Center (1929-1937). Liang sought to reinterpret Chinese timber-framed architecture within Beaux-Arts Classicism and expounded this approach to his many students after he returned to China in the 1920s.

The second section of Part III offers three different takes on 20th-century Chinese architecture. It examines the interplay of native Chinese architects with foreign visitors, which encouraged the Chinese in “designing outside their cultural bubbles.” Examples include Tsinghua University in Beijing and Fudan University in Shanghai, with designs by New York’s Henry K. Murphy and Richard H. Dana.

This section also deals with Western-influenced Chinese architecture that perpetuated Republican ideals, such as the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Auditorium (1926-1931) in Guangzhao, designed by Lü Yanzhi, a Cornell University graduate who had worked in Murphy and Dana’s “Oriental Department” in the late 1910s. Chinese construction that sought to promulgate Socialist change is covered as well, with an account of the (unrelated) architects Zhang Bo and Zhang Kaiji, who designed Tiananmen Square’s Great Hall of the People and Revolution and History Museums of China, respectively, in the 1960s.

The third and final section of Part III deals with the politics, planning and paradigms of urban design in China. The Republican era is represented by buildings such as the Foreign Ministry (1933-1934) in Nanjing, “designed in a Western classical manner, an acknowledgement of its function as a center of contact with other nations.” The later Socialist era is covered with a look at city design after the inauguration of urban reforms in 1978 and the subsequent sprawl of increasingly urbanized areas.

Although filled with handsome photos contemporary and historic, Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts is no coffee-table book – this volume is a thoughtful and far-ranging account of international trends in architecture, which have been too little known in the U.S. It fills an important need and is certain to find its place in every serious library of architectural history.