Features

Book Review: Carrère & Hastings: The Masterworks

Carrère & Hastings: The Masterworks

by Laurie Ossman and Heather Ewing; photographs by Steven Brooke

Rizzoli International Publications, New York, NY; 2011

320 pp; hardcover; more than 200 full-color photos; $75

ISBN 978-0-8478-3564-5

Reviewed by Clem Labine

The authors begin this handsome monograph with a provocative assertion: If John Merven Carrère had been gunned down by an ex-lover's jealous husband instead of dying in a taxi accident, Carrère & Hastings would be as famous today as McKim, Mead & White. Such is not the case, unfortunately. Because Carrère & Hastings lacks the tabloid notoriety that Stanford White bestowed on his firm, Carrère & Hastings is well known today only to architectural historians.

In the early 20th century, however, the two firms were equal rivals. Upon Carrère's death in 1911 at the zenith of his career, The New York Times pronounced: "As an architect he had, probably, no superior in this country and very few equals." Though The Times may have been engaging in a bit of elegiac hyperbole, it was true that in the early 1900s, Carrère & Hastings frequently competed with McKim Mead & White for the same projects (most notably the New York Public Library) – with C&H often emerging the winner.

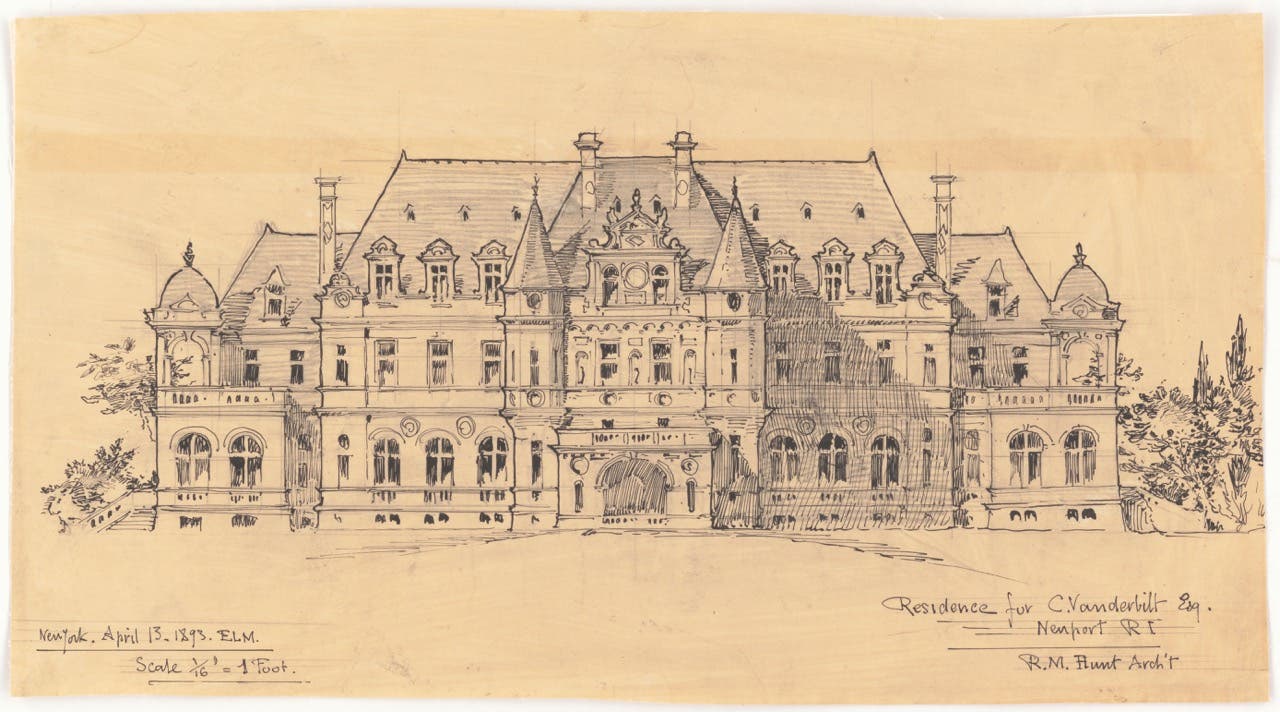

In the effort to restore John Carrère and Thomas Hastings to their rightful place in the pantheon of early-20th century American architects, this monograph presents 27 of the firm's masterworks of the Gilded Age, including the firm's towering achievement – The New York Public Library. But the firm created many other American landmarks to which their names are rarely attached. Between 1885 and 1924 the firm designed hotels, retail and office buildings, country estates, elaborate townhouses, theaters, institutional buildings, churches, monuments and exhibitions in major cities that included New York, Washington, London, Paris, Rome and Havana. Their clients were the elite of the Gilded Age, with names such as Flagler, Carnegie, duPont, Rockefeller, Frick, Harriman, Morgan, Gould, Astor, Payne, Whitney, and Vanderbilt.

It Started at McKim, Mead & White

John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings both studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in the early 1880s – and both joined McKim, Mead & White in October of 1883. But they didn't stay long, leaving in 1885 to set up their own partnership. It was Thomas Hastings' social contacts that soon had them on the road to success. The Standard Oil tycoon, Henry F. Flagler was a friend of the Hastings family, and he selected the young – and untested – firm to design a luxury hotel and resort, The Hotel Ponce de Leon, in St. Augustine, FL.

Carrère & Hastings did not let Flagler down. The Hotel Ponce de Leon, designed in a Spanish Renaissance style, was an immense success upon its completion in 1888. Though quite traditional in appearance, it incorporated some major innovations, including being the largest poured concrete structure built up to that time and was wired for electricity from the outset. As part of the process, Carrère also developed a Beaux-Arts urban plan for St. Augustine – five years in advance of the Beaux-Arts plan for the "White City" that was the centerpiece of the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition.

With the St. Augustine development hailed as a success, and with Carrère & Hastings' skills at cultivating powerful clients, the firm soon found itself among New York's elite architectural firms. So it was natural when the newly formed New York Public Library announced an architectural competition in 1897 that Carrère & Hastings was among the 88 firms invited to compete. Carrère & Hastings then made it to the list of five finalists – which also included McKim, Mead & White. But many were surprised (including Charles McKim) when Carrère & Hastings was judged the winner. After landing the coveted library commission, Carrère & Hastings became New York's "hot" architectural shop, with many wealthy clients vying for their services.

Bridging the Beaux-Arts and Art Deco Periods

It is amazing that many Carrère & Hastings works survive in near-original condition – and gratifying that this monograph brings them so vibrantly to life. Individual essays tell the story of the firm's well-known masterpieces, such as the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater and the New York Public Library, as well as lesser known and rarely seen homes of the Gilded Age elite. Lush photography by Steven Brooke is reproduced on a large scale, so readers can relish the firm's skill at integrating high style, exquisite materials, and beautifully rendered surface enrichment – all exhibiting the designers' Beaux-Arts training.

Short essays provide the social and cultural context of the clients and their architects for each of the 27 projects illustrated. The book reveals a unique time in American history when great wealth combined with private and public ambition to produce magnificent architecture that expressed the confidence of a nation which suddenly found itself a great world power. The illustrations also show how Thomas Hastings – the firm's principal designer – became more refined and restrained in his use of ornament as his skills matured.

A reader looking for a lot of theory and discussion of architectural details will probably be a little disappointed. And the authors do not supply floor plans, so it is often difficult to appreciate the full scope and dimension of these masterworks by just looking at the photos. Nonetheless, the authors furnish rich descriptions of the basic characteristics of the structures along with vivid details of the circumstances of their construction. This gorgeous volume shows us a bygone age when creating beauty in the built environment was a main desideratum – and Beaux-Arts scientific rationalism provided the tools for achieving that lofty goal. TB