Features

Building Technology Heritage Library

Strangers to preservation are ever amazed at how historic building devotees, who they assume to be lost in the past, are in fact among the earliest adopters of cutting-edge, 21st-century technologies. The internet, of course, is everyone’s digital darling, and a prime example of how it’s being turned to traditional use is the Building Technology Heritage Library where period trade catalogs—throw-away paper brochures decades and even centuries old—are collected and digitized for limitless global access and a new life.

According to Mike Jackson, FAIA, who spearheads the effort, “Period trade catalogs can be highly valuable to preservation professionals who are assessing structures for their historical evolution, environmental safety, or any other architectural engineering conditions.” He explains that being commercial in nature, and designed for relatively short lifespans, trade catalogs are not found in most architectural libraries. “So in 2010 the Association for Preservation Technology in collaboration with the Internet Archive, launched the Building Technology Heritage Library (BTHL) to create an online archive of these historic technical documents that makes them useful to the widest audience.”

The BTHL is hosted by the Internet Archive, a San Francisco-based non-profit digital library founded by internet visionary Brewster Kahle with a mission of “universal access to all knowledge.” As Jackson points out, “These materials are available to the general public at no charge, and all are in the public domain.”

What is the BTHL?

Like much about the so-called information superhighway, creating a digital library of historic publications sounds easy—just pour them into the virtual punchbowl of cyberspace for anyone to sample—but in reality there’s more to it than meets the virtual eye. Historic trade catalogs are technical, descriptive documents—typically booklets of a few dozen pages—that are lean on literary merit but rich with graphics, photos and product and marketing information.

Originally widespread and free, most are now, paradoxically, hard to find and even precious. “Only a few architectural libraries around the country recognized the value of trade catalogs enough to start collections,” explains Jackson, among them Avery Library at Columbia University in New York and Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, DE. “There are several local libraries with specific collections, such as the Chicago company catalogs at the Chicago Public Library,” he says.

Another example is the University of California at Santa Barbara, home to the Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection. Romaine was a rare book dealer from Massachusetts who began collecting trade catalogs in the 1920s. “Romaine wrote the seminal book on the subject—A Guide to American Trade Catalogs, 1774-1900—and amassed a collection of over 40,000 catalogs that the University is still organizing and we hope to work with at some point.”

For all its unlimited digital reach, the BTHL keeps a tight rein on its scope. “We focus on the technical and trade literature, which nobody else has been doing,” says Jackson. “A lot of the late 19th- and early 20th-century publications on building construction and design were captured by Google Books because they were in the major engineering and architectural libraries. But the trade literature wasn’t in those libraries; it’s only in these few, isolated, special collections.”

Jackson singles out the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal for special credit in this regard. “When we started our effort, we posted an open request of, in effect, ‘If you’ve got a collection to share, please let us know.’ They raised their hand and offered to share their collection, which was fantastic.”

When the CCA began developing their library in the 1980s, he says trade literature was on their wish list and included a big acquisition from The Franklin Institute of Philadelphia, an archive strong on 19th-century material “We basically had someone at the CCA for a year scanning about 3,800 documents from their collection.”

Says Jackson, “In the next year or so, we’re aiming towards the 10,000 item mark, starting with the Avery collection in 2017.” He says they typically partner with libraries that already have the complete subject cataloging in place, making it easier to complete the data entry. “We’ve got several more collections that we’re interested in working with in the future—it’s just a matter of funding. Long-term the BTHL could easily grow to 20,000 items, there’s that much material out there.”

Jackson acknowledges he has been a primary booster of the BTHL since day one, but far from alone. “Dean Koga, an architect with Building Conservation Associates in New York and the current president of APT, was really critical in launching the library,” he says. “Being on the APT board then, Dean promoted the BTHL at the organizational level while I was developing it as kind of the operational management chief.”

On a financial level, he highlights the Driehaus Foundation in Chicago as instrumental with early funding to get the project started. Ongoing supporters include the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT) and the Historic Preservation Education Foundation, as well as the Driehaus Foundation.

The Ken of Catalogs

What makes the BTHL so useful is the way it opens up to the world information that formerly was obscure to the point of being incredibly rare. “To appreciate the scarcity of trade catalogs,” explains Steven Schuyler, a bookseller who specializes in architectural publications (www.rarebookstore.net), “you have to understand the meaning of the word ephemera.” Often described as transient, everyday, printed items of paper, Schuyler’s favorite example is a ticket stub for a 1960s Beatles concert. “Maybe it made it into your wallet, maybe it wound up in the trash can. However, if you were smart enough to save the ticket, that’s an instance of really collectible ephemera today.”

Explains Schuyler, “The thing about trade catalogs that makes them exceptionally ephemeral is that they were designed to be obsolete after a certain amount of time.” The idea, he says, was that once you received the latest, greatest catalog from the manufacturer with a new price list, you were supposed to throw the old one away. “That’s why they became so scarce, and today we realize that what’s really rare is the material that wasn’t officially collected or saved.”

Jackson’s own embrace of period catalogs goes back to the 1970s when he had something of a trade ephemera epiphany. “I was working on Main Street programs,” he says, helping to revitalize traditional business districts, “when I saw a Mesker Storefront catalog reprinted in an early APT Bulletin.” Mesker refers to two sibling companies out of St. Louis and Evansville, IN, who manufactured, designed and marketed prefabricated, ornamental, sheet-metal facades and storefronts that became endemic in small- to medium-sized towns across America from the 1880s to the mid-20th century.

“‘Wow, this is really cool!’ I thought until I found an original Mesker catalog for sale at a flea market and bought it,” says Jackson. “From there on I started collecting architectural trade catalogs, finding them here and there in used bookstores, ephemera shows, and the like.” Jackson put his ever-growing collection to work as head architect of the Illinois State Historic Preservation Office for 27 years.

Trade catalogs document not only the products they push but also the larger markets, industries, and times in which they flourish. “The rarer material has origins in the early advertising of the 19th century,” says Jackson. Catalogs of all kinds got a boost from the U.S. postal system when it classified them as aids to the dissemination of knowledge (eligible for lower postal rates) and the advent of the rural free mail delivery service after 1896.

“Over half the population was rural then, so a man like Richard Sears was a genius to put this mammoth catalog together to reach the rural audience.” Adds Schuyler, “One of most interesting things about the trade literature is the price lists and advertisements for other companies it often contains—sometimes more important than the original text.”

Jackson says the BTHL collection stops in 1963 because trade catalogs after this date, though still published in print, remain in copyright. From the 1990s onward, technical commercial literature becomes increasingly digital and, potentially, will one day find its way into online libraries where it can be located and retrieved.

Bringing the information treasure trove in trade catalogs into wider hands is not a new idea. In the 1970s, pioneering reprints from specialty publishers such as Dover, Da Capo, and The American Life Foundation, helped fuel interest in catalogs and spread information to historic building scholars as well as those researching furniture, lighting and other collectibles.

“In the late 1980s Avery Library microfilmed about 1,800 catalogs from their collection in an early effort to disseminate them to other research libraries,” recalls Jackson. The microfilm didn’t catch on, he says, “but it all comes together in the new, digital online era.”

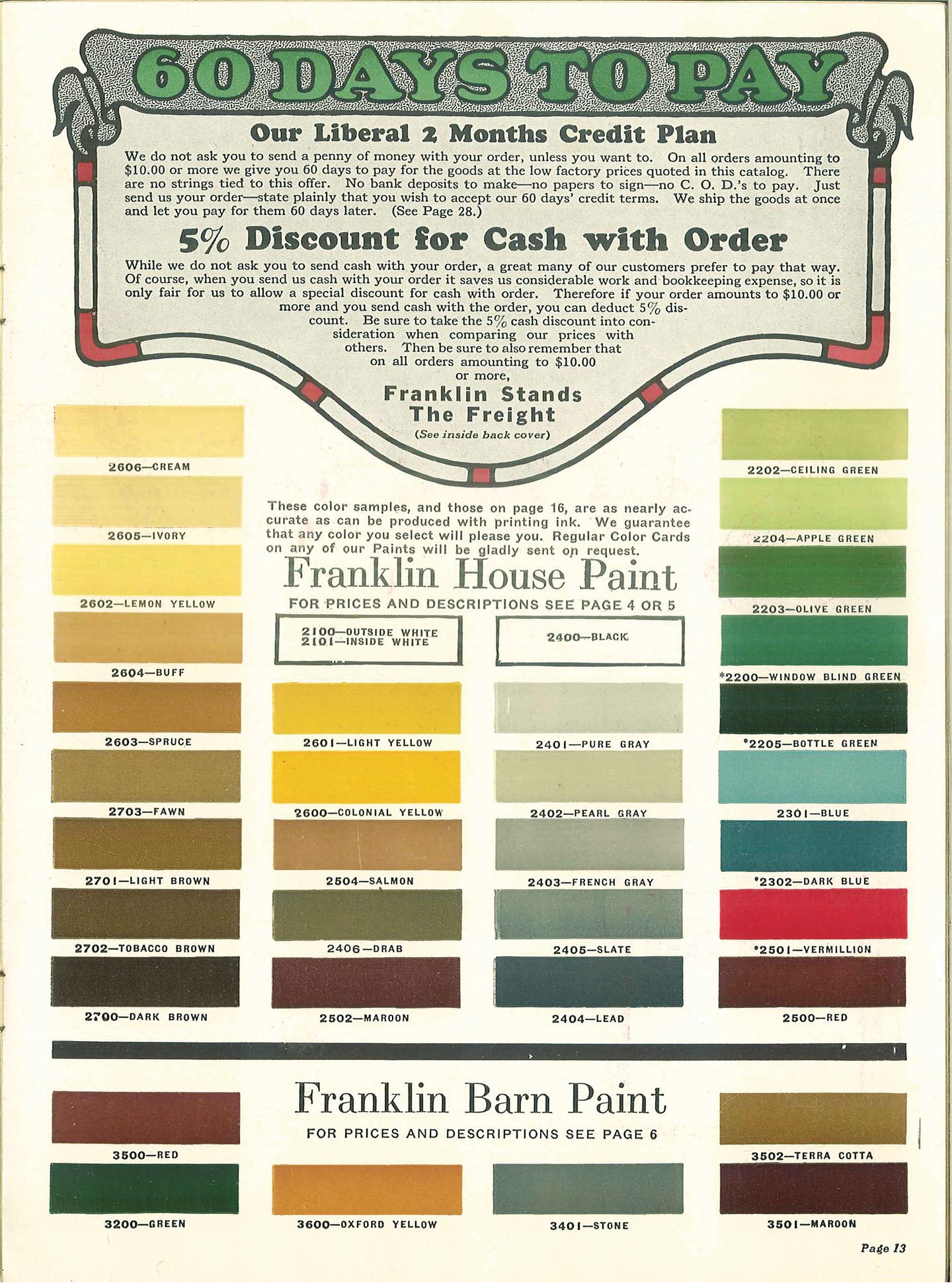

In fact, the BTHL is not the first to put trade catalogs online either. “Some material—the jewels, so to speak, such as 19th-century paint catalogs with great color plates of Victorian houses—have already been scanned and included in various collections.” He notes that the Smithsonian Institution has a fantastic collection of 400,000 items, but only the tip of this iceberg is as yet online.

“Actually, the BTHL has scanned a lot of paint literature from the 20th century, courtesy of Mary Jablonski, a paint and building conservator in New York,” says Jackson. While presenting accurate paint colors in trade literature has always been extremely difficult (color information shifts in traditional, four-color printing and digital scanning alike), such documents are invaluable for all kinds of building research and restoration.

Judging by the numbers, the BTHL is a success with users and sponsors alike, but there’s still room to grow. “We know we’re getting 50,000 downloads a month,” says Jackson, “yet very few of these people tell us why they look at this material.” All users need to report, he says, is that they found a catalog useful for XYZ reason. For example, Jackson says one user wrote that a catalog helped restore an old building, while other material became legal documents in an environmental justice suit in California.

He adds, “We’d love to have more users comment by responding to the Internet Archive ‘add review’ prompt. If they see something they like or are hoping for more, that’s where these reviews can help us develop the BTHL even further.”

A Sweet Home for Old Sweet’s

When asked if there are any thin spots in library’s coverage, Jackson says the collection of early Sweet’s Catalogs is pretty good from its debut in 1906 up to the 1930s, but “weak” thereafter, especially in the 1950s. “We’d love to have people donate Sweet’s Catalogs from the 1940s, ‘50s, and up to 1963 because these books have assembled huge amounts of data on the Modern-era commercial building sector,” a category of ever-increasing interest to preservationists.

He adds that since the Sweet’s Catalog Files of the post-war era are actually encyclopedia-like compilations of manufacturers’ information published by F.W. Dodge Company, for scanning these multi-volume sets will have to be disassembled. “Perhaps, there’s a retired architect out there looking to downsize.” For more information, contact the BHTL at digitization@apti.org.

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.