Features

Book Review: Andrew Jackson Downing Essential Texts

Andrew Jackson Downing Essential Texts

edited by Robert Twombly

W.W. Norton & Co., New York, NY, 2012

400 pp; soft cover; a number of b&w illustrations; $35

ISBN 978-0-393-73359-4

Reviewed by Martha McDonald

“Architect and Gardener to the Republic,” the introduction to Twombly’s book, highlights Downing’s short life (1815-1852) in Newburgh, NY, and points to his reputation as “the father of American landscape architecture, as his profession is now called, and a father of the urban park movement in the United States, as well as the foremost advocate of village, indeed national, beautification.”

Downing began writing about horticulture when he was 16. He wrote more than 140 essays, many of then editorials in the journal he founded, The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste. He also wrote four books on landscape gardening, fruit trees and residential design. Downing followed his father into the nursery business but eventually devoted all of his time to The Horticulturist and offered his services as a professional landscape gardening expertise.

He collaborated with Alexander Jackson Davis from 1842 until 1850 on at least five residential commissions, with Downing as the consultant and Davis as the architect. In 1850, Downing went to England to study landscapes to study landscapes, and returned with a young architect who worked as his assistant for two years, Calvert Vaux.

Downing was working on what would have been his largest project, the “Public Grounds” in Washington, DC, when he died in 1852. He and his family were on board the Henry Clay headed for Washington, DC, when the vessel caught fire and Downing was among 70 people who drowned.

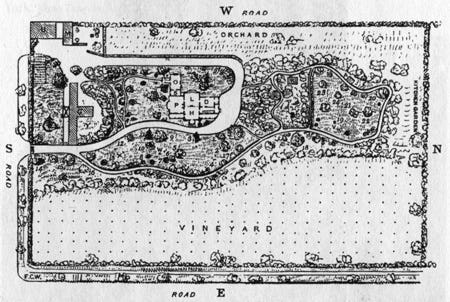

Twombly has selected a number of Downing’s writings and presented them in six sections: “Architecture and Building,” “Landscape Gardening,” “Parks and Other Public Places,” “Village Beautification,” “Horticulture,” and “Agricultural Education.” Each section contains a number of Downing’s essays, and each one of these is prefaced by an introduction by Twombly. Most of the illustrations (all are black-and-white photos or drawings) are located in a section at the center of the book.

The writings reveal a person devoted to the wellbeing of the general public. He quite often mentions the value of public parks and institutions.

His interests ranged from simple country homes to grand public sites.

For example, a chapter in the first section entitled “On Country Houses,” written in 1846, states that rural homes should be simple with “neat and quiet grounds,” and “within the reach of almost every landholder in America.” He then proceeds to provide guidelines, including drawings, for a simple country cottage.

The second section on “Landscape Gardening” starts with a letter to the editor of The New-York Farmer and Horticultural Repository published in 1832 when Downing was only 17, signed “X.Y.Z. Newburgh.” He noted, “That branch of horticulture called landscape gardening is, as yet, completely in its infancy among us,” and warned against “straight line planting,” and the common fault of “placing the residence too near the public road.” Other chapters include “A Chapter on Lawns,” “Hints on Flower-Gardens,” “The Management of Large Country Places,” and “A Chapter on School Houses.”

The third section, “Parks and Other Public Places,” reveals Downing’s belief in the need for public parks “open to all classes of people, provided at public cost, maintained at public expense and enjoyed daily and hourly by all classes of persons.”

In “The New York Park,” published in 1851, Downing praises Mayor Kingsland’s proposal for “a green oasis for the refreshment of the city’s soul and body.” He only complained that Kingsland’s proposal, at 160 acres, was too small, noting that “Five hundred acres is the smallest area that should be reserved for the future wants of such a city.” In his notes for this section, Twombly points out that the state legislature authorized the purchase of 778 acres in 1853, and another 65 acres in 1863, bringing New York City’s Central Park to 843 acres.

The book concludes with a section on agricultural education in which Downing bemoans the fact that irresponsible farming is depleting the nation’s soil and calls for the creation of agricultural schools. A useful detailed index and suggestions for further reading are found in the final pages.

Twombly, a retired professor of architectural history at City College in New York, and author of other books and anthologies, became interested in Downing during visits to the two remaining Jackson-designed landscapes. One is the 1851 Headley property just south of Newburgh, NY, Downing’s home town. The other is the 1951-52 Matthew Vassar estate in Poughkeepsie, NY. Twombly was disheartened to see that very little of Downing’s original work remained, and that even Downing’s home and its 11-plus acres no longer existed. This led him to study more about Downing and his influence on others such as Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, and to develop this most informative book. It is a book that could be read straight through, and revisited often by often by anyone with and anyone with even a passing interest in landscapes and the public environment.

Twombly has brought to light Andrew Jackson Downing’s remarkable contributions to the American landscape. As one who greatly appreciates our public parks, and who has, I will admit, often taken them for granted, I will never stroll through one again without thinking of Downing.