Features

Review of The Classicist No. 8

The Classicist No. 8

edited by Richard John

Institute of Classical Architecture & Classical America, New York, NY; 2009

212 pp; numerous illustrations; softcover; $45 (free to ICA&CA members)

ISBN 978-0-9642601-2-2

Reviewed by Eve M. Kahn

The eighth edition of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Classical America’s journal, The Classicist No. 8, is the lengthiest and liveliest in the series’ 15-year history. How many other nonprofits’ publications would manage to summarize a few eons of human achievement, plus the traditions’ modern-day repercussions, in so many pages of colorful illustrations and insightful prose typeset in Venetian and Roman serifs with second-century ancestry?

Half the volume is devoted to essays about under-appreciated historical revivals of Classicism. In 1819, we learn from Notre Dame architecture professor Richard M. Economakis, a British military engineer named Sir George Whitmore (1775-1862) designed a government center for Corfu made of Maltese limestone and fronted in a Doric colonnade modeled after Parthenon precedents. Economakis analyzes the building’s multicultural facets: from the Britannia statue that once crowned the roofline alongside a Venetian lion and a Corfuote rudderless ship, to the “Palladian reverberation” of the interior’s proportions.

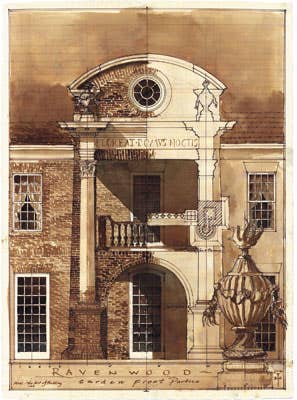

The Classicist also profiles two 20th-century innovators, Charleston-based architect Albert Simons (1890-1980) and British architect/critic Sir Reginald Blomfield (1856-1942). College of Charleston art historian Ralph Muldrow explores Simons’ “ubiquitous yet unobtrusive” work, ranging from Georgian Revival houses to Low Country plantations, austere stuccoed college buildings and the occasional Ionic-columned, balustraded, brick gas station. By 1949, Simons had conceded the mainstream to Modernism, although he worried that “there is very little poetry or enchantment in any of it.”

Blomfield was even gloomier, according to University of Miami architecture professor Katherine J. Wheeler. He warned of the “insidious and far-reaching” effects of rejecting the past, an unsound fallacy “foredoomed to failure,” while prolifically designing the likes of a 1926 vaulted memorial arch in Belgium for British soldiers and a 1913 stone quadrant for Piccadilly Circus.

Of course Blomfield was too gloomy. In portfolios of a dozen architects’ recent work, The Classicist shows how traditionalists have quietly won battles in many corners of the planet – and not just by designing rich peoples’ houses. The mini portfolios cover churches by Duncan G. Stroik scattered from Indiana to California; scalloped-gable, Bermuda-inspired public buildings in Florida designed by Cooper Johnson Smith Architects and Khoury & Vogt Architects; and townhouse crescents in England and France byFairfax & Sammons Architecture (with Ben Pentreath) and the Italian firm of Pier Carlo Bontempi.

Equally heartening are The Classicist’s essays on what the next generation is learning:

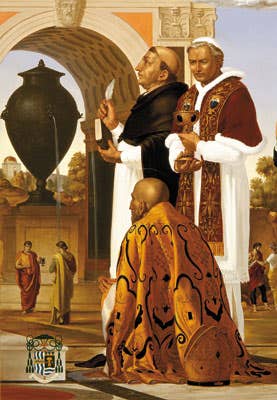

The Doric pavilions that Georgia Tech students have proposed for a Wall Street ferry terminal and a YMCA in Manila; the Gothic dorm for Yale that Notre Dame students believe would look “as if it has always been there”; and the exquisite pencil drawings and oil paintings of ancient statuary that are coming out of the ICA&CA’s own Grand Central Academy of Art.

The Classicist took in work by so many authors, however, that not all the prose is consistently good. Economakis’ sentences in particular could have used haircuts. A fairly typical example goes like this: “While in many ways typifying early-nineteenth-century eclectic attitudes, the formal nuances, complex organizational strategies, and subtle cultural and political references that pervade Whitmore’s work may be offered in riposte to the argument that Late Georgian architecture was compromised by rote copying, capricious application of antique and Renaissance precedent, and a disinclination toward analytical and metaphorical thinking.”

And the journal’s descriptions of new buildings, sometimes a few sentences long, can skim along with generalities about “design that can be enjoyed by the frequent visitors to the area.”

But where else, between two covers, would you find an Oxford philologist’s 1760s description of battling grass fires in Turkish coastal ruins, an ode to contemporary muralist Leonard Porter’s 2009 scene of Greek wind gods anticipating the sacrifice of Princess Iphigenia, and some hi-res photos of architect Eric Stengel’s Tennessee barn with steel straps wrapped around column bases “to resemble the bindings on a horse’s legs”? The ICA&CA has to be lauded, again, for bringing to light so many thought-provoking, non-proselytizing variations on its core themes. TB