Features

Book Review: Gardens for a Beautiful America 1895-1935

Gardens for a Beautiful America 1895-1935: Photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston

by Sam Watters

Acanthus Press, New York, NY; 2012

Published in collaboration with the Library of Congress

380 pp; hardcover; 250 color illustrations; $79

ISBN 978-0-926494-15-2

Reviewed by Eve M. Kahn

The photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) sometimes heard herself compared to "an ant with a huge last year's grasshopper," while lugging large-format cameras and a typewriter around the country. For 60 years, she documented properties designed by architects and landscape architects as prominent as McKim, Mead & White, Horace Trumbauer, the Olmsteds and Beatrix Jones Farrand.

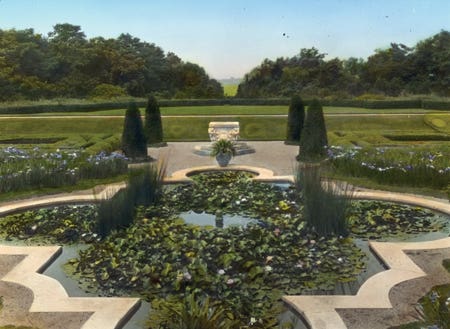

A patient African-American chauffeur, Huntley Ruff, at times drove her around. Every angle of the landscape interested her, from overgrown lakefronts to new colonnades where vines were still choosing their paths upward. She started work at sunrise, climbing ladders and leaning out windows, "looking for the light that 'gives roundness,'" the historian Sam Watters writes in Gardens for a Beautiful America 1895-1935: Photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston.

The research took Watters five years. The Library of Congress owns much of Johnston's work but had scarcely processed it. (The images are now online and searchable at www.loc.gov/pictures.) The photographer herself did not believe in accurate labels; she focused instead on traveling and lecturing and getting more business.

In the library's Johnston collection, Watters reports, "More than 600 of the 1,134 slides have no identifying marks." For research assistance, he turned to "archivists, librarians, curators, and scholars in the 15 states and four countries where Johnston photographed," he writes.

The global team effort has produced a sumptuous and tantalizing volume. We see what Johnston wanted us to see, "weedless, ever-blooming, flawless, and without people," as Watters puts it.

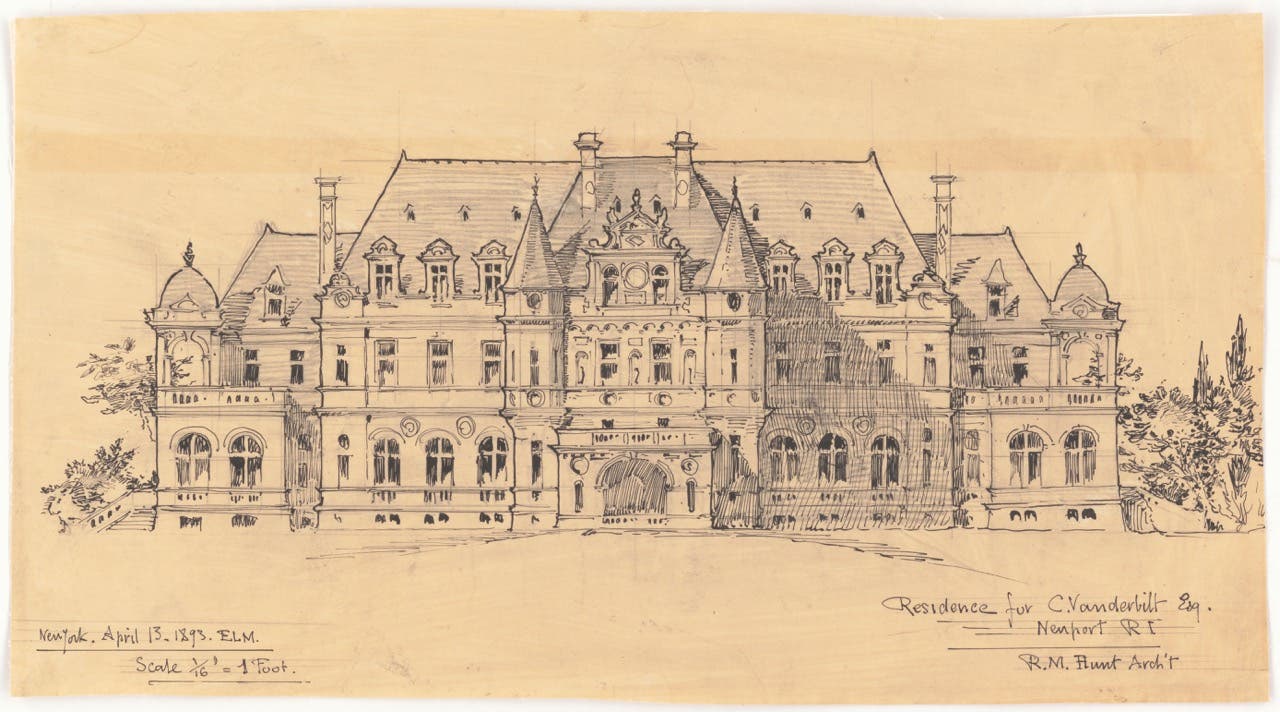

Johnston took black-and-white shots with wide-field lenses and then had professional colorists add dabs of tinting to the blossoms. Her industrialist and old-money patrons could afford rows of trees and statuary stretching to the horizons. The clientele's last names are as prominent as Pell, Pratt, Vanderbilt, Auchincloss, Astor and Doubleday. Johnston's acquaintance circle also included culturati like Louis C. Tiffany, Edith Wharton, the naturalist John Burroughs and the interior designer Elsie de Wolfe.

But Johnston really preferred gardens that could enlighten and uplift the poor.

In the footsteps of Arts and Crafts philosopher-reformers like Elbert Hubbard, "she herself became an advocate for social improvement through design in nature," Watters writes. Johnston gave countless slide lectures to garden clubs mostly full of rich ladies, and then tried to teach them to help the less fortunate by setting up public green space and encouraging plant-growing programs in poor neighborhoods.

She often showed the ladies a Manhattan tenement stairwell and doorway, overflowing with potted and boxed trees and vines. The space was cultivated by a janitor she described as "the most ardent and enthusiastic horticulturist I ever met," with a knack for rescuing "the faded Easter plants thrown out on the ash-heap."

Johnston's lectures had titles both erudite ("Garden Lore and Flower Legend") and practical ("Problems of the Small Garden"). She flashed her slides in quick time-lapse succession, "to walk viewers along flower borders" and give a sense of the passage of seasons and years, Watters explains.

The photographer had begun her career with much parental encouragement: her father, a senior clerk at the U.S. Treasury, built her a rooftop studio at their Washington home, overlooking thickets of roses and wisteria. But as an adult she was utterly self-sufficient; her only longtime significant other was another photographer, a talented divorcee named Mattie Edwards Hewitt. The two women lived together in New York in the 1910s, and then had an acrimonious split."She develops and enlarges the pictures," Johnston once disparaged Hewitt in an interview with Vanity Fair.

Watters organized his volume as Johnston had done in many of her lectures, by region. Full captions for the glass negative scans annoyingly appear at the back of the book, so readers have to keep flipping back and forth to learn about client biographies and project specs. These short texts could easily have been integrated into the wide margins of the plate pages. Even more maddening, the index is chopped into three vague sections: "Galleries, Organizations, People," "Gardens, Expositions, and Locations," and then "Subjects."

Despite these minor logistical impediments for researchers, Watters has delved deeply into Johnston's psyche. He details the order of slides she used in her presentations, and lists reference books she owned with wonderful titles like The Formation of Leafmold and Continuous Bloom in America.

One version of her slide show had no explanation of the actual estates on view and their construction nuts and bolts. The scenes just flashed onscreen as someone read poems with names like "To a New Sundial" and "The Crocus Flame." TB