Features

Book Review: Americans in Paris

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

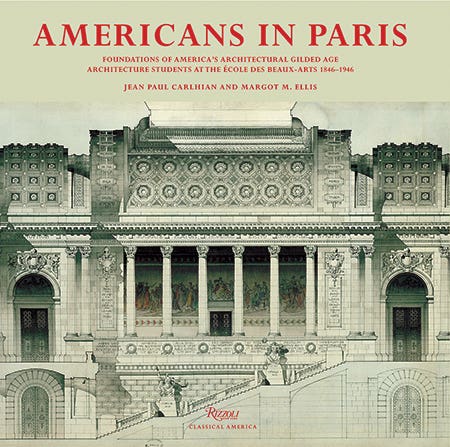

Americans in Paris: Foundations of America’s Architectural Gilded Age

By Jean Paul Carlhian and Margot M. Ellis

Rizzoli, New York, NY

240pp; hardcover; 200 color and b&w illustrations; $85

ISBN: 978-0-8478-4340-4

Reviewed by Annabel Hsin

The research for Americans in Paris: Foundations of America’s Architectural Gilded Age by Jean Paul Carlhian and Margot M. Ellis began in 1976 when Carlhian decided to work on a sequel to Edmond-Augustin Delaire’s Les Architectes Élèves de l’École des Beaux-Arts, a book chronicling students who studied at the École from 1793 to 1907. Carlhian’s particular interest was in documenting American students at the École beginning with Richard Morris Hunt, the first one admitted through the concours d’admission and concludes with William Richard Potter Delano, the last true student accepted through the entrance competition in 1933.

Indeed, Carlhian is well suited to write such a book, which is the first English language account of the architectural program, as he was born, raised, and educated in France as well as a graduate of the École who received the best thesis prize. For decades, he worked at the renowned Boston firm Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott, and was most noted for designing the National Museum of African Art and the Sackler Gallery of Asian Art, both Smithsonian Institutions in Washington. He has also taught at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and was an American citizen. He was more than equipped to comment critically on the structures designed by the former American École students and has the educational expertise to evaluate whether the students applied the lessons learned from the prestigious French institution.

Americans in Paris is presented as a large format book (12x12 in.) with large illustrations, generous two-page spreads and with enough text to whet the appetite of the serious reader. Although the scant captions providing the most basic information—the name or content of the illustration, its creator and year it was created—leave something to be desired.

In the introduction, Carlhian explains, “This work does not pretend to be a complete survey of all the American architects who were admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts. There are too many of them…. I have concentrated on buildings designed by EDBA-trained architects—those that are still standing, used as originally intended, and visited by me.”

A listing of all 503 students, both alphabetical and chronological, can be found in the appendices. The list is separated with those who earned the EDBA title (Élève de L’École des Beaux-Arts) and those who won admittance through the Paris Prize Competition in New York. A third list consists of the 144 students who have earned the Diplôma, “the ultimate challenge of an École education.”

The book is loosely organized in two halves with the first detailing the journeys of the American students and the latter devoted to individuals, firms, projects, and competitions. The first two chapters, “Teachings at the École” and “The Paris Prize,” takes up more than a quarter of the book and provide vivid explanations of what it means to be an École student, from the rigorous entrance competition that only admitted 40 students at a time to the six concours or exercises required after a student achieves first class status as well as the difference between earning admittance via the Paris Prize when compared to the conventional method.

With chapters entitled “The Very First,” “Those Who Died Too Young,” and “Firms,” the latter part of the book shares interesting facts about the students and their work. For instance, the architectural firm is an American invention unheard of in the European countries. Having studied under the atelier system of École, it was a natural move for EDBA-trained colleagues to come together and tackle projects as a team, and during the Gilded Age there was an abundance of complex commissions. Carlhian has identified 200 or so firms or partnerships with EDBA-trained members versus less than two dozen single practices headed by an individual. McKim, Mead & White; Carrère and Hastings (the EDBA duo); and Warren & Wetmore were the firms featured.

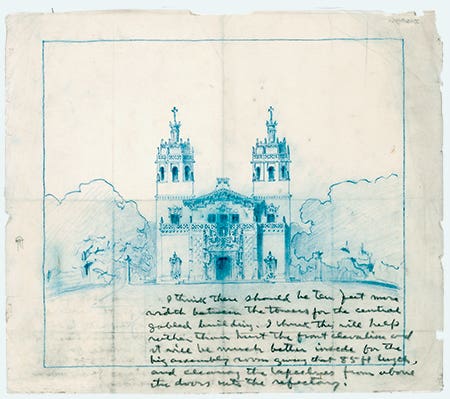

Julia Morgan, listed under the chapter “Individuals,” was not only the first American woman to hold the EDBA title but the first woman ever admitted in the École’s history. The school never expected women to take part in the entrance examination so had no restrictions against them. It was made clear to Morgan that she shouldn’t expect to receive a diploma nor actually practice architecture. After returning to the U.S., however, she went on to design William Randolph Hearst’s beloved San Simeon ranch, now a National and California Historical Landmark.

It is these back stories of the school’s noted students that make Americans in Paris a pleasurable and entertaining read. Carlhian lends a unique perspective into the curriculum of the École, not only was he a former student of the prestigious school but he was also a teacher, practicing architect and an immigrant, albeit migrating in reverse and under much less difficult circumstances. This book is the perfect addition to the library of any reader interested in American architecture, history and the Gilded Age.