Features

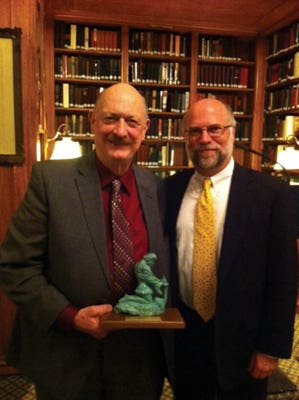

Clem Labine Awarded the 2012 Newington-Cropsey Award

By Steven W. Semes

One of my personal missions over the years has been to try to make sure that the contributions of those who have been faithful soldiers in the campaign to reform and revive the arts in our time are duly recognized, especially in my own field of architecture. While Clem Labine, as far as I know, is not an architect himself (though he is an expert restorer), he has made important contributions to the discipline of architecture. Hardly anyone has done more to promote and encourage the recovery of the Classical tradition in architecture and urbanism in our time. For more than a quarter-century, Clem has offered a platform for new Classical design, new urbanism, and historically-informed preservation work through the magazines, conferences, exhibitions and personal advocacy that he founded and continues to inspire.

Clem did more than build the platform; he has also been an important actor on that platform: He created the critical nexus of communication and dissemination by which the most important movements in architecture today have been able to make their case to the public despite a professional and academic press that has been indifferent or hostile to them. It is a very different field we work in today than it was 25 years ago, and much of that progress is due to Clem's pioneering efforts.

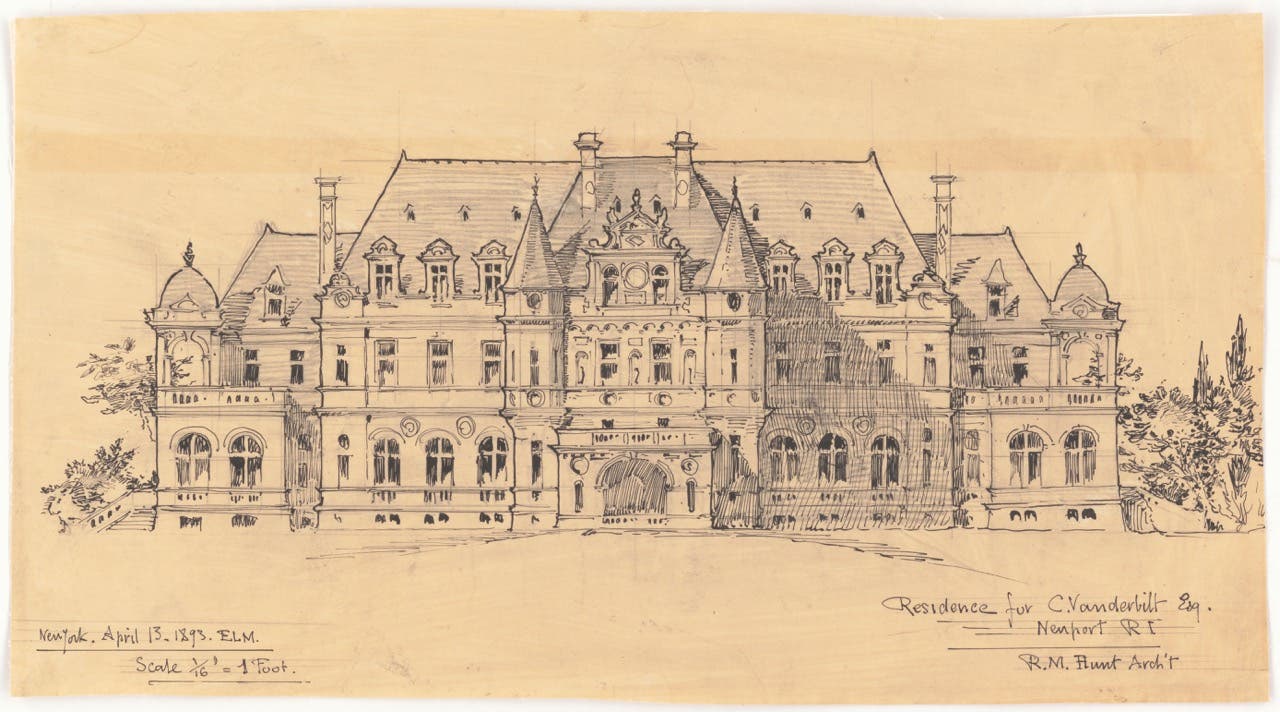

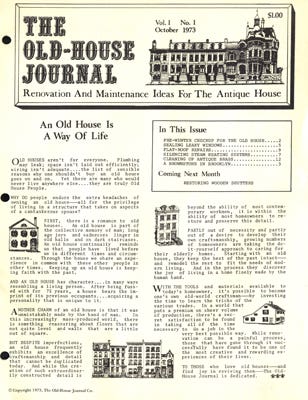

It started in 1972, when Clem left his editorial and marketing position with McGraw-Hill to pursue his interest in preservation, or more accurately, his obsession with restoring an 1883 Victorian brownstone house in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn, NY. The following year he founded Old House Journal as a resource for others like himself who were engaged in restoring and searching out appropriate materials for old houses. This choice might seem a strange one for a chemical engineer trained at Yale, but he had the advantage of NOT having received a degree in architecture there: We have to remember that in the 1970s you could not find a more unpopular or un-chic thing to do than to love old 19th-century buildings, particularly Victorian houses.

But even then, attitudes were slowly changing.

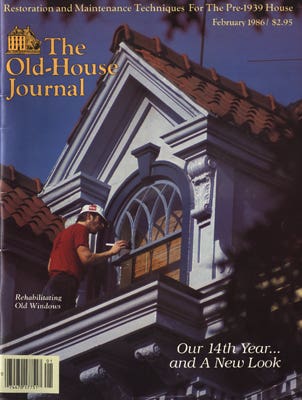

Clem saw his own work in the context of the emerging new appreciation of 19th-century architecture and the coming-of-age of the preservation and adaptive use movement.The Old House Journal grew from a modest photocopied newsletter into a mainstream glossy magazine that showcased and encouraged restoration and appropriate new uses for buildings that had, by the late 1970s, become the object of a massive "back to the city" movement. Urban neighborhoods began to see new economic life and the return of their architectural character after a generation or more of neglect. The magazine was an essential resource for architects, homeowners, contractors, craftsmen, neighborhood activists, and anyone else interested in the revitalization of cities.

By the late 1980s, Clem realized that the restoration movement was not limited to houses; civic, commercial and institutional buildings, too, were increasingly the object of transformation. Further, he realized that the revived skills and newly available materials that were making it possible to preserve, repair and restore old buildings could also be used in new construction.

Weren't modern architects always saying, with a bit of a sneer, "I would be happy to design traditional new buildings, but where are the craftsmen?"? The craftsmen were, in fact, right down the street, restoring brownstones, fabricating cornices and balustrades, carving stone, laying brick, running plaster moldings, and crafting metalwork. Factories were once again producing terra cotta, decorative ceramic tile, copper gutters and flashings, accurately designed replacement windows, stylistically correct light fixtures – everything.

Clem understood that this revived industry was not just for restoration but that it could revolutionize the construction of new buildings as well. At this auspicious moment, in 1988, Clem founded Traditional Building, a magazine at first dedicated to the restoration industry – and that alone would have been an important contribution – but it then began to evolve, and readers watched the transformation of American architecture, public and private, unfold in front of their eyes on its pages. It is no exaggeration to say that this publication gave the Classical movement its voice.

It was an exciting time in our field.

We were in the twilight of Postmodernism, the moment when the witty historical allusions of the 1970s were giving way to a recovery of the formal language of Classicism. The most forward-looking architects were tired of both bland orthodox Modernism and incoherent historical allusions. The Classical tradition was being rediscovered and revitalized, but the mainstream professional and academic press, solidly in the grip of the Modernist establishment, had largely ignored its reappearance. A new generation of architects looked in vain in the pages of Architectural Record or the ever-diminishing number of architectural media outlets for recognition of new Classical architecture and traditional urbanism. Then Clem changed the game.

In 1990, he published an article in Traditional Building about the re-emergence of Classical design among a small group of architects dedicated to recovering and continuing the millennia-old tradition that traces its lineage back to ancient Greece and Rome. The article provoked intense interest and Clem decided to look deeper at this new cultural phenomenon. For the November/December issue the following year, under the banner headline "The Classicists are coming!" the magazine profiled Philadelphia architect and a leader of Classical America, Alvin Holm, and featured projects by other Classical designers as well. In his editorial, Clem wrote:

"One attractive aspect of Classicism is that it is much more than an architectural style. Classicism is not just columns and capitals (you can have a perfectly correct Classical building without a single column or pilaster). Rather, Classicism is a humane philosophy, of which architecture is merely one element – a vehicle by which Classical ideas can be made visible. For the true believers…the Classical tradition is a system of ideas that have universal application. The Classical concepts, originated by the Greeks and Romans, have been continually developed and refined throughout subsequent Classical eras. "

He went on to say:

"Two principles touch upon core truths that I believe are going to make Classicism and Classical architecture extremely relevant for the 1990s: We certainly need an increased awareness of civic responsibility and the ecological consequences of our actions. Classical architecture, with its human roots and ready accessibility, is an ideal vehicle to symbolize civic and environmental issues in the coming decades. Because of its social relevance, the Classical has the potential to have far greater impact on the 1990s than the Victorian Revival had on the 1980s."

Two decades later, we see how prescient Clem was.

The revival of traditional architecture and urbanism, of which Classicism is both the foundation and a subset, remains of crucial relevance in discussions of sustainability and the future of the public realm today. Since that ground-breaking issue, Clem has consistently showcased new Classical projects, essays about Classical design, and profiles of practitioners; but he has gone even further, supporting the return to traditional architecture and urbanism through his editorials, conference programs, book reviews and most recently, his blog, "The Civitas Chronicles." Sustainability and restoring civic culture remain the two pillars of his argument.

For the true believers, the Classical tradition is a system of ideas that have universal application.

It was Clem's ingenious notion to bridge the old-building/new-building divide, showcasing rehabilitation and restoration work alongside new construction in traditional styles. Doing so made Traditional Building a most powerful engine for transforming our discipline. Clem's publications are now the principal outlet for information about resources, products, books and other supports for the preservation industry, but – more importantly, I would argue – they remain virtually the only place where professionals and laypeople can find extensive coverage of the ideas and work of designers practicing new traditional architecture today.

This intersection of preservation and new traditional design rather unexpectedly raised an important issue: It turned out that some preservation authorities, of all people, were discouraging the use of historical styles for additions to historic buildings or new construction in historic districts. Citing documents like the Venice Charter of 1964 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation of 1977, preservation boards and authorities in many places were actively discouraging new designs in the same styles as the historic settings in which they appeared.

Clem was one of the first to understand the incoherence of this attitude and has consistently argued for stylistically appropriate new work in historic settings. For the Traditional Building Conference in Boston in 1997, he invited me to join the panel he chaired to discuss the relationship between new Classical practice and preservation issues. Since then, Clem's magazines and subsequent conferences have been an essential arena in which to refine these ideas, which are now changing the way we think about the relation between new and old architecture. My own work in this direction owes everything to Clem's encouragement and ongoing support through publications and educational programs.

Traditional Building was so successful that by 1999 Clem created a sister publication devoted to the residential side of the field, Period Homes. This magazine has continued to supplement the public/commercial/institutional projects covered in Traditional Building, which is able more effectively to advance the slow but steady progress of new traditional architecture into building types that, even now, remain more resistant to historically-informed design than the residential market.

Clem understood that it wasn't enough to wait for good new traditional work to come in over the transom so, in 2002, he created the Palladio Awards to recognize excellence in a broad range of building types, regions, styles, budgets and uses, including new buildings, restorations, and sympathetic additions to historic properties. Now celebrating its 11th anniversary, the Palladio Awards joined the Arthur Ross Awards of Classical America (and later the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art), and was followed by a growing list of local awards programs by regional chapters of the Institute, and theDriehaus Prize and Henry Hope Reed Medal of the University of Notre Dame in directing public attention to the wealth and quality of new traditional architecture and sensitive preservation across the United States. They certainly aren't seeing it in the mainstream professional media.

I cannot end my remarks without also noting that in a time when debate in the arts and culture has become increasingly difficult and even rancorous, Clem Labine is that rare person who can make his points and state his convictions in ways that elevate the discussion. His warmth, intelligence, humor and gentleness go a long way to making him an outstanding spokesman for a new humanism in our collective life. Somehow, it all seems to fit together into one coherent and invaluable package: the devotion to the art of architecture, to civility and urbanity, to decorum and courtesy. Clem represents all of these at the highest levels.

Congratulations, Clem, and keep up the good work! TB

Steven W. Semes, an associate professor of architecture at the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture, was the academic director of the University's Rome Studies Program from 2008 to 2011. A practicing architect for 30 years, he has designed a wide variety of projects for preservation and new construction throughout the United States. Semes is the author of The Future of the Past: A Conservation Ethic for Architecture, Urbanism, and Historic Preservation (2009) and The Architecture of the Classical Interior (2004), and was a contributor to The Elements of Classical Architecture (2001), all published by W. W. Norton & Co. His essays and reviews have appeared in Traditional Building, Period Homes, American Arts Quarterly, and the National Trust Forum Journal. His blog can be found at www.www.traditionalbuilding.com. He is a Fellow Emeritus of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art and was educated at the University of Virginia and Columbia University. For more information, visit his website, www.thefutureofthepast.net.