Features

Clem Labine Award Goes to Steven Semes

By Gordon Bock

The simmering preservation scuffle over what additions to historic buildings should – or shouldn't – look like may smack of Gulliver's Travels to the person on the street, but the implications in every town are very real. If you recall the satiric novel, when Lemuel Gulliver first encounters the kingdoms of Lilliput and Blefuscu they are poised to go to war – over the proper way to break eggs. Though the additions clash is neither so trivial nor so easily settled, architect and educator Steven W. Semes has helped ease the fray by framing the debate. In recognition of this service and his decades-long career he is this year's recipient of The Clem Labine Award.

Inaugurated in 2009, The Clem Labine Award honors an individual who, over an extended period of time, has demonstrated a personal commitment of time and energy to the creation of public and communal settings in which the civilizing values of the humanist Classical tradition can flourish. The winning individual may be an architect or designer, artist or artisan, community leader, author, or member of some other profession, and often the winners' professional and personal lives blend into a seamless whole.

As described by Clem Labine, whose own longstanding career as a publisher, journalist and design proponent inspired the award, "The key point is that it is not just a 'professional achievement' award for what a person is paid to do between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. Rather the award is given for someone who's an example of 'A Life With A Purpose' in the cause of promoting humane values in the built environment." This year's award will be presented to Steven W. Semes at the Traditional Building Exhibition and Conference to be held October 20-23 at the Navy Pierin Chicago.

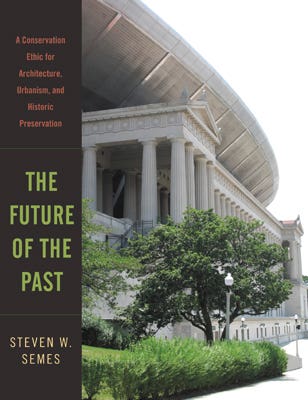

In a recent phone call from Italy, where he is the Academic Director of the Rome Studies Program and Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame, Semes reflected, "An award like this forces you to look back over years and see is if there some kind of thread or storyline to your work, and I think in my case there clearly is." Of course, the Selection Committee wholeheartedly agreed. In the words of Labine, "Steve was selected for this year's Award because of the efforts he has devoted for the past two decades to create a more humane urbanism – work that is exemplified by his splendid new book,The Future of the Past: A Conservation Ethic for Architecture, Urbanism, and Historic Preservation,and the new preservation ethic that he has put forth.

"Steve has combined his work as an architect, teacher, author and lecturer to spread his gospel of 'appropriate' new construction in historic areas – rather than architecture that presents radical contrast to the historic context. More than any other single person, Steve has blown the whistle on the terrible damage that has been done to historic districts through harmful interpretations of Standard #9 of The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation (and also #3 to a certain extent.) Promotion of new construction that is adversarial to old buildings has become the default standard for many landmark commissions and design review boards. Steve has devoted a lot of his personal life – as well as professional time – to demonstrate the aesthetic and intellectual folly of this point of view."

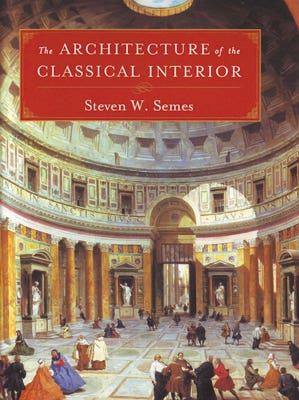

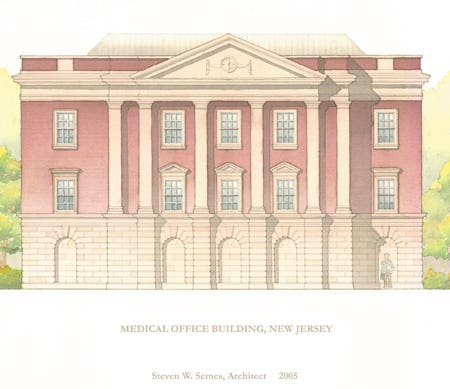

A practicing architect for 30 years, Semes has designed a wide variety of projects for preservation and new construction throughout the United States. Semes is also the author of The Architecture of the Classical Interior (2004), and was a contributor toThe Elements of Classical Architecture (2001), all published by W. W. Norton & Co. His essays and reviews have appeared in Traditional Building, Period Homes, American Arts Quarterly, and theNational Trust Forum Journal. He is a Fellow Emeritus of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Classical America and was educated at the University of Virginia and Columbia University.

A long path to today

His mother, an aspiring interior decorator, was part of the milieu too. Says Semes, "All of them had an interest in traditional design, which in their eyes meant essentially American Colonial; they liked Chippendale furniture, houses with porches, nice moldings, paneling, things of that kind. So the way I grew up prepared me to feel at home in an environment where even the most recent creations are somehow part a long tradition of making or building similar things."

By the time he began studying architecture at the University of Virginia in the 1970s, the world around him was sending a more mixed message. "Even though the explicit curriculum was thoroughly modern, there was no way to avoid falling in love with Thomas Jefferson's work," he says. "So, my architectural education happened on two contrary levels. On one level, my professors were telling me what I was supposed to do according to the Bauhaus; on another, more subliminal level, Thomas Jefferson's example was telling me what architecture was all about. Ultimately the latter won."

Facing a weak job market after college, Semes landed a stint at the National Park Service in Washington, DC, that set the course of his career and gave him a seminal vicarious experience. "I was hired as a Historical Architect," he recalls, "a strange title for a 21-year-old kid and the kind you could only have in government." The Park Service trained Semes to review grant proposals for National Register sites but, more memorably, brought him into the office that created The Secretary of the Interior's Standards. Says, Semes, "While I had no personal involvement with it, I was in the very room – a fly on the wall – when that document was first being drafted."

The Secretary of the Interior's Standards established guidelines for maintaining the historic character of existing built structures, but still left Semes with questions about new work. Then in 1977, he recalls, "I heard a lecture by Robert A.M. Stern, who was the first person to suggest to me that, in fact, contemporary architects could design buildings that had some of the same qualities and values as historic buildings. So that was a real 'Ahah!' moment. I decided to go off to Columbia University and study with Stern and other marvelous people to learn how to design new buildings that enter into a meaningful dialogue with old buildings."

Another epiphany was to come in the early 1980s. "It was not until I studied Classical architecture seriously with Alvin Holm in New York," says Semes, "that I actually figured out that, yes, you could design new Classical architecture, that it was not something that is dead and gone. So it is particularly satisfying to me to receive this award the year after it has first gone to Alvin Holm."

Fast forward to 2009 and the publication of The Future of the Past, you could almost hear the architectural community collectively sigh with relief that somebody had taken the additions bull by the horns. Says Semes, "I love the bull image because, unless you're an experienced matador, you can find that the bull is bigger than you thought it was. So while I may have grabbed its horns, I think we're still waiting to see who's going to say 'uncle' first."

As Semes explains, the real question posed by his book, and the driver behind the additions tug-of-war, is how are we supposed to manage the built environment in which we live? More than ever, most people recognize that historic buildings can continue to have useful lives if they can change and grow a little bit – indeed, to survive at all today they must.

How then to do so without removing the character that makes them worthy of preservation in the first place? "Clem [Labine] is one of my mentors and an inspiring figure in my career," Semes says. "Back in 1997 he invited me to talk on the subject at theTraditional Building Conference, so he was the first to suggest that additions to historic buildings might actually interest people."

The interest was certainly there, and it has grown to become a critical architectural issue in the sustainability minded 21st century. Adds Semes, "My objective is not to make anyone defensive, but to get people talking about what they think are the most important ideas and principles underlying decisions about how new and old relate. It's not my job to tell people what buildings should look like. It is my job to suggest some terms that help make clearer what they think certain buildings should look like, given where they are and what they mean."

Judging by the honor of this award, it's a job he has done well, and one worth breaking some eggs over.TB

Gordon Bock, co-author of the forthcoming book The Vintage House, lists his upcoming courses and workshops at www.gordonbock.com.

Steven Semes shares ideas on traditional architecture at his blog, The View From Rome.