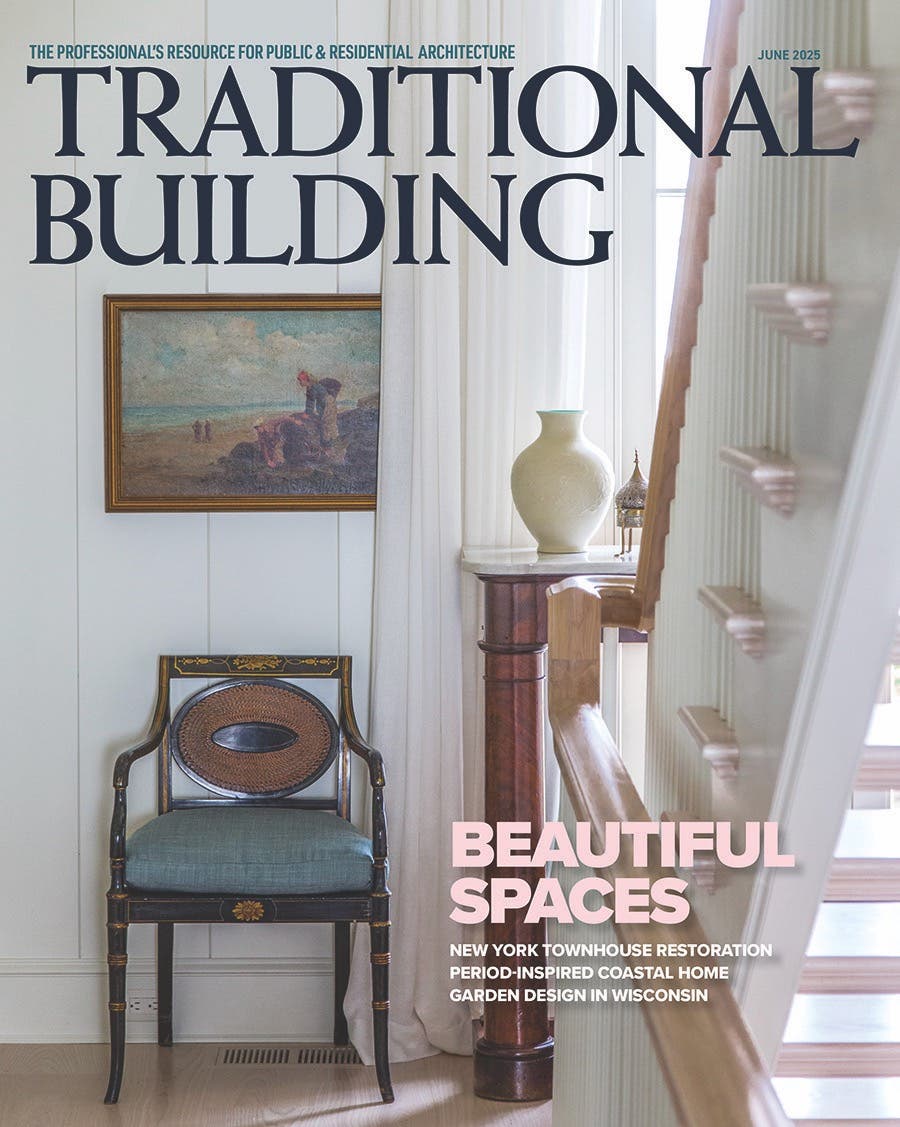

Carroll William Westfall

Tradition in the Vernacular and the Classical

Thank goodness for traditional architecture. Without it we would not have decent vernacular for the great mass of builidngs or spectacular classical buildings serving our most important purposes.

Tradition guides both the vernacular and the classical that anchors the opposite ends of the spectrum of buildings that, like our activities, run from down-home private houses to important public, civil roles. In traditional architecture and urbanism, all along the spectrum from vernacular to classical (not in the sense of a style but as the best) buildings participate in beneficial reciprocal relationships.

The vernacular builder, as the late English architect and educator R. W. Brunskill noted, works within traditions composed of “a series of conventions built up in his locality.” His buildings serve common functions such as providing shelter and places to make and sell things. He pays attention to what is current and selling, with local materials “used as a matter of course, other materials being chosen and imported quite exceptionally.” Guided by formal traditions, he produces the backgrounds for urbanism’s grand classical public buildings.

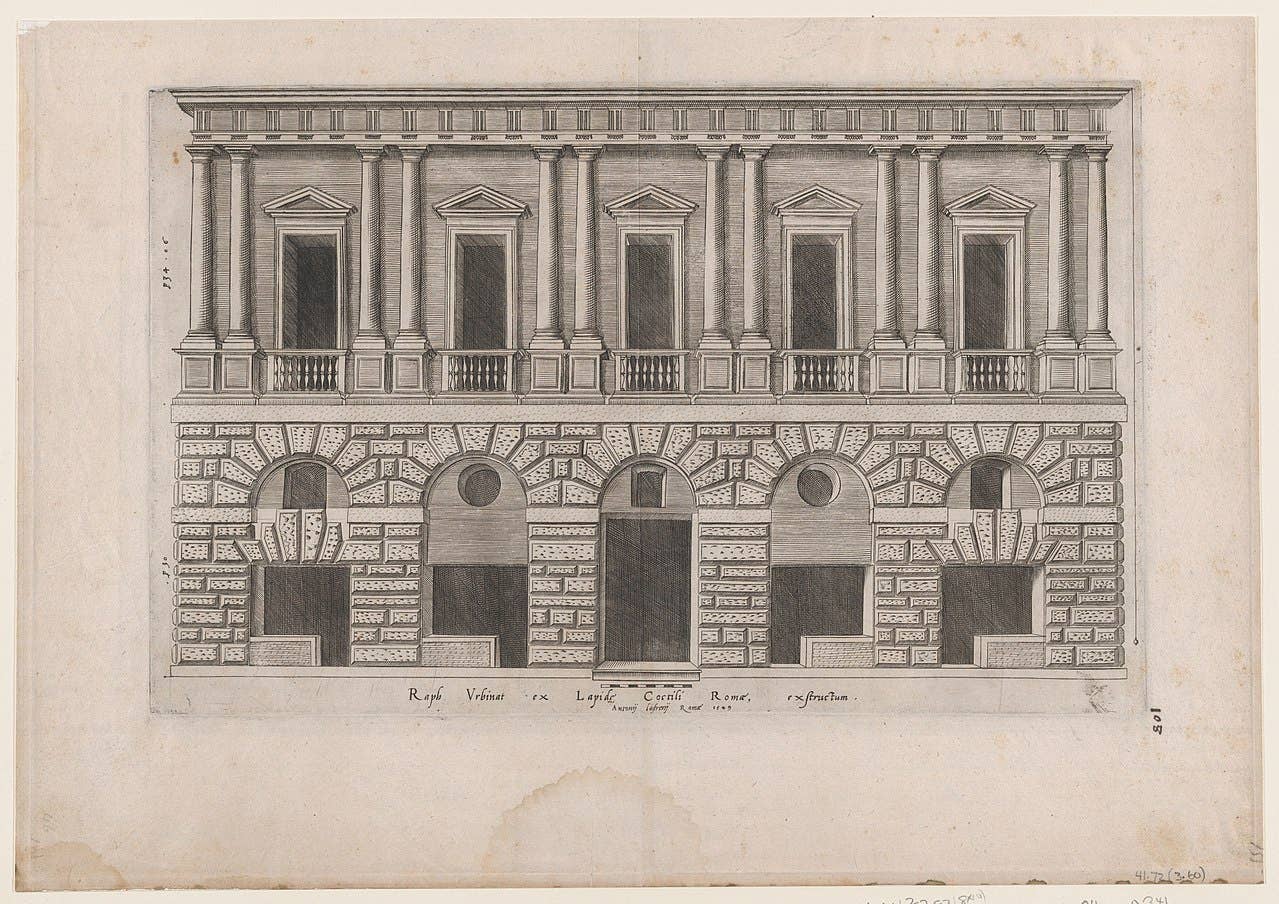

Those grand buildings are much fewer in number, and they serve activities that are both more public and more important in fulfilling our human aspirations. They encompass schools, libraries, theaters, courthouses, city halls, churches, and so on. They are highly visible, and the standards of craftsmanship, of attention to design and quality of materials are diluted when used in their vernacular neighbors. In this way the public buildings stand out against the private, vernacular background just as public services and actions do within the common public good that the urbanism serves.

Tradition is the guide all across the spectrum. A common formal tradition allows all the buildings to belong to one another while dilution based on the calibration of the public or private purposes introduces variety. In the vernacular, the local or perhaps even regional formal properties will be most prominent in the configuration of the core, for example of party wall row houses or the American Foursquare, as will the building’s size, its placement on its site, and the economic class it is intended for. Within that commonality the composition and detailing used to face the street absorb changing fashions, generally following the changes imported for their classical superiors.

This pattern prevailed as streetcars and interurbans allowed expansion of urban areas to reach additions with larger lots and connected cities to towns on the fringes, but trusted patterns collapsed after the automobile killed public transport. The scale of the economics of construction and land development ballooned, planning was introduced with zoning in control, and builders were active in the suburbs while architects set about modernizing city centers.

For a while shops and offices were strewn as single-story rows behind off-street parking. It was then collected in ever larger shopping centers. And soon the center-city workers left tall, downtown commercial towers prominent in the urbanism and moved into sleek, glassy medium height buildings isolated within landscaped grounds.

Tradition now lost its customary role as guide for continuity and unity and host to innovation’s variety. Something similar happened in our individual lives where private and public activities became ever more estranged and unattached to tradition’s civil guidance. Knowledge of how to act in public that was embedded in custom and habit, always different from region to region, city to city, and even neighborhood to neighborhood, was lost, and with it we lost the awareness that participation in the public life is necessary to fulfill private aspirations. The private back yard became more prominent than the public park as a place for relaxation and getting together with family and friends.

Tradition became distrusted, too often regarded as a dead hand inhibiting innovation. Tradition without innovation is indeed sterile, but in a live tradition there is a constant interchange within the spectrum from classical to vernacular and vernacular to classical, which is the point of the story that Vitruvius and later theorists told. The tree trunk becomes a column, the primitive hut becomes a temple, and the temple becomes a model to dilute to make a house. Tradition does its work within an architecture that is a communal undertaking, absorbing improvements across time as many individuals introduce new ideas and variations to serve the beauty that is the end of architecture. And so do citizens whose lives together and across time contribute to and draw from the common good of civil society.

In this movement the architects of the major public buildings bear a special responsibility, which includes providing a model for the best in public and private buildings. A well-known complaint of our third president was about Virginia’s vernacular buildings.

It is impossible to devise things more ugly, uncomfortable, and happily more perishable. … [A] workman could scarcely be found here capable of drawing an order. The genius of architecture seems to have shed its maledictions over this land. Buildings are often erected, by individuals, of considerable expence. To give these symmetry and taste would not increase their cost. It would only change the arrangement of the materials, the form and combination of the members. This would often cost less than the burthen of barbarous ornaments with which these building are sometimes charged. But the first principles of the art are unknown, and there exists scarcely a model among us sufficiently chaste to give an idea of them.

As a remedy he offered an innovation within tradition by adapting a revered model of antiquity, the ancient Roman temple of Nimes in France, to serve as the new Capitol of Virginia. When he sent its model from Paris back to his friend Jams Madison in Virginia, he wrote, “Its object is to improve the taste of my countrymen, to increase their reputation, to reconcile them to the respect of the world, and procure them its praise.”

Today’s architects seek only innovations and scorn tradition. Their clients’ eye is on the bottom line, and their eye is on the latest fashion or on the profession’s and the critics’ best-new-thing-in-show prize. They see no connection between their creative inventions and the role that important public buildings play in suggesting innovations in the vernacular, modeling respect for civil conduct, and contributing to the common good.

So of course today’s vernacular builders wisely stand apart. Vernacular builders continue to evoke tradition: it is what their buyers want. But they lack instructive models in traditional architecture and the training for the eye that good, new traditional buildings provide. Continuity and quality have long held strong in such common kinds of buildings as party wall row houses. Two streets in Richmond, Virginia show the continuity. One in a prosperous 19 century area, the other in a workingman’s district from a little later that Urban Design Associates rehabilitated in the 1990s with many new party wall row houses, some here visible in the next block. The city’s Georgians are also difficult get wrong, as two buildings of similar c. 1940 vintage show, one in a swell district, the other strictly middle class. It would seem that the American Foursquare could easily be done right, but the comparison of three buildings proves me wrong. Note the materials, proportioning, detailing, and composition of two new ones one from 2018 and 2019 compared to a nearby one from 1911.

The important, public builidngs used to offer high standards that the builders of private buildings strived to reach. Now those buildings offer mere personal exhibitionism in both lowly commercial buildings and courthouses and museums. This leaves the vernacular builders to swap ideas rather than improve their practices, all of which results in the continued deterioration of our cities visually and civilly.

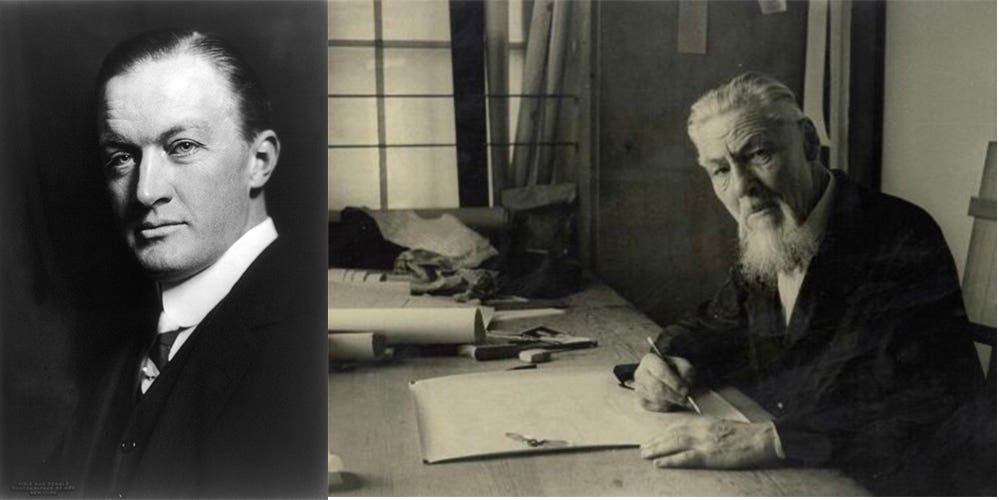

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.