Features

The Challenges of Preserving Historic Gardens

By Martha McDonald

Those seeking to preserve historic gardens face some of the same challenges that preservationists face when restoring and rehabilitating buildings. Questions such as what should be saved, what should be replicated or restored, what period do you restore to, and how do you conform to modern standards, are just some of the challenges that architects and designers face when renewing a building. The same questions are also pertinent to gardeners working in historic gardens.

There is one big difference, however: plants continue to grow, change and die, even as various owners manage the gardens. Gardens continue to evolve over the years, changing in small and large ways, and they quickly languish if they are not maintained. In addition, furnishings such as arbors, fountains, benches and pavers are an integral part of these gardens.

Historic gardens come in all sizes and shapes, ranging from well-known, large institutions like Biltmore in Asheville, NC, with 8,000 acres, and the 1,000-acre Winterthur in Delaware, to small versions such as the Madoo Conservancy, a two-acre romantic location in Sagaponack, Long Island, NY. Many had famous founders and designers, such as George Vanderbilt and Olmsted at Biltmore, and Henry Francis du Pont and Marian Coffin at Winterthur, while others were less grand and less well funded, yet important all the same.

Some have been well funded and maintained, while others languished, and have struggled over the years. Estates such as Biltmore and Winterthur fall in the first category, while Vizcaya and Untermyer fall in the second.

What makes a successful historic garden? “It’s a little bit of everything, the design, the furnishings, the furniture. It all has to be consistent,” says Lenore Rice of Seibert & Rice, importers of terra cotta planters and urns. “Undoubtedly, a successful garden requires a combination of factors. Enthusiasm, funding and knowledge are key – particularly when it comes to the maintenance, enhancement or restoration of historic environments,” adds Simon Scott of Haddonstone, manufacturer of replica garden ornaments and architectural stonework.

One big question with preserving historic gardens is: Do you restore to the original design and plantings or do you evolve and change over time? Spokespeople from the Biltmore, Madoo Conservancy, Untermyer Gardens and Winterthur all land somewhere between “save the original” and “evolve over time.” All note that the most important concept is the design intent.

“Historic gardens and landscapes should be true to their origins whilst adapting to the modern world,” Scott says. “In other words, change for change’s sake should not be an option. However, change to allow, say, improved disabled access, improved transport access or visitor facilities to encourage increased enjoyment of a heritage amenity should be encouraged.”

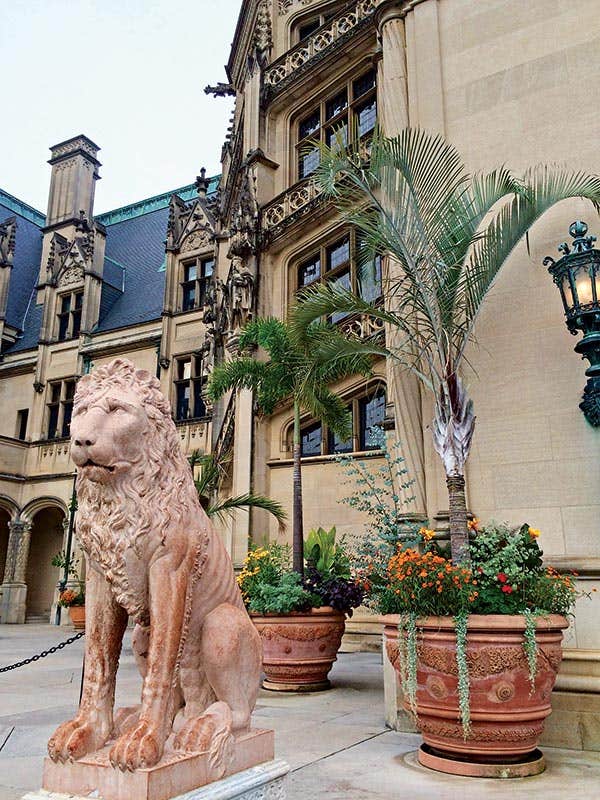

Biltmore

At Biltmore in Asheville, NC, director of horticulture Parker Andes points out that in the late 1800s and early 1900s people like George Vanderbilt were building country estates. “At that time, scientific forest management was just coming to the U.S. The first such forest was here,” he says, noting that the gardens consists of the “home grounds,” the gardens near the house, and the surrounding 8,000 acres of forests and fields.

“Gardens and plants grow and die and shade out others. Our philosophy is that we maintain the design intent that Olmsted and Vanderbilt started,” he said. One example of how he has maintained the design intent while adjusting to today’s environment is the three-mile drive to the house. Andes explains that in Vanderbilt’s time the guests would have taken a horse and carriage up this road, at a speed of about four miles an hour, and people were up high, so the viewpoint was slow and higher, the height of horse back.

“Historic gardens and landscapes should be true to their origins whilst adapting to the modern world,” Scott says. “In other words, change for change’s sake should not be an option. However, change to allow, say, improved disabled access, improved transport access or visitor facilities to encourage increased enjoyment of a heritage amenity should be encouraged.”

“Our guests today drive up in cars at 15-20 miles an hour and they are lower, so the view is faster and lower,” he says. After studying original drawings from 1893, Andes and his staff decided to widen the pond and made the waterfall more parallel to the road, so today’s guests experience a similar historic vista.

“The term is re-creating, not restoration or renovation,” Andes says. “We are re-creating and maintaining the design intent with today’s reality.” Furnishings such as pots and benches are important, he adds. “We have them recreated in the Victorian style.”

Winterthur in Delaware also saw its beginnings in the early 1900s under the direction of Henry Francis du Pont. Linda Eirhart, director of horticulture, describes it as a “wild garden” advocating the use of both exotic and native plants to create a more naturalistic gardens. Similar to Biltmore, the garden is more formal around the house.

“Our mission is to preserve the design style,” she says. “We continue to add new plants but they have to fit the design intent. The challenge for historic gardens is that you have to understand the design intent and make sure you preserve it.”

As for furnishings, Eirhart says some of the historic follies, pergolas and benches have been preserved and others were reproduced. Being a public garden, new benches have been added for guest’s comfort and enjoyment of the garden. Historic benches were reproduced for areas such as the Sundial Garden where they are integral to the design.

Vizcaya

Another historic turn-of-the-century garden is Vizcaya in Miami. “We do not subscribe to the idea that a historic garden needs to be kept exactly as it was,” says Ian Simpkins, deputy director for Horticulture & Urban Agriculture. “We have a very strong historic precedent in place, and we abide by that. However, that does not mean that gardens need to be kept exactly as they were when they were completed in 1922. We have the latitude to experiment with new plants as long as we work within the historic fabric.”

“When I got here, the gardens were a shadow of what they had been,” he says adding that he has been there nine years. “They had not been maintained. We worked with what we had. We went back to the original bed designs, removed a lot of plants and trees and installed other trees, back to what it was originally.” He currently works with a staff of eight (compared to 60 in earlier days), to restore the gardens. “We stay true to the design intention, but we had to streamline to make sure we were able to maintain it.”

Structures and architecture are a critical part of the garden, Simpkins adds. “Pots are used to frame views, to provide resting spots for the eye, to soften the architecture and to showcase rare and unusual plants.” As for benches, he says he was able to find composite benches “that are very close to the original design.”

“It’s really important that cultural landscapes are held to the same importance as historic structures,” Simpkins stresses. “They tell the story of a nation and in some cases they are more important than the structures.”

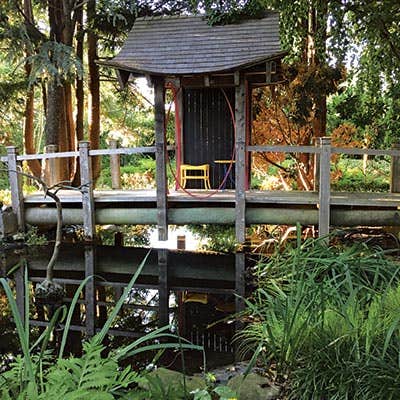

Madoo

A smaller, and more recent, yet still historic garden, is the two-acre Madoo Conservancy on Long Island, NY. The garden itself was started in 1967 by artist Robert Dash, but it contains older structures, such as a barn dating back to circa 1740. “Change was a big part of Madoo from the beginning,” says Alejandro Saralegui, director of horticulture. “Some elements are signature,” he adds, “but we are open to re-interpretation. We look at the way the garden is used, what our needs are and we play that against what Bob planted.”

One example of change are new varieties of roses. “The roses that have been planted are only giving one flush of blooms, but we are a public garden and people want to see more color,” says Saralegui. “This is what we keep in mind when we replace something. Bob planted this 40 years ago; would he have planted it now?”

“This is a turn-of-the-century, Bloomsbury style garden,” he notes. “It’s very romantic. Part of the challenge is keeping that feeling as we change to accommodate the public and events. We want to keep the mystery.”

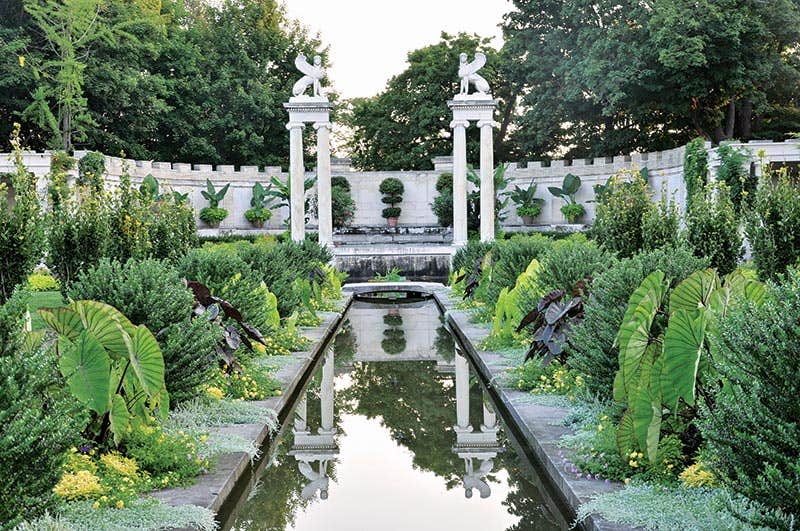

An example of a garden making a comeback is Untermyer Gardens in Yonkers, NY. It consisted of 150 acres on the Hudson River when Samuel Untermyer acquired it in 1899. After his death in 1940, the gardens languished and the house was razed. Its walled garden is based on Persian gardens with waterways dividing it into four quadrants and walls anchored with octagonal towers at the corners.

In 2011, former Yonkers resident, preservation architect and NYC landmarks commissioner Stephen F. Byrns took an interest in the gardens and formed a conservancy. Working on a volunteer basis with one full-time gardener (Timothy Tilghman), he began restoring the garden, starting with the walled garden and then moving to other areas.

Just recently, he left his position as principal at BKSK Architects in New York City, to become full-time president of the conservancy. “We will have six people working in the gardens this summer,” he says, “three full time and three seasonal. The walled garden was the first project and then we were able to raise money for capital projects.”

“Untermyer’s plantings were like the Rockettes, showy but not sophisticated. What we will have will be more sophisticated, but less labor intensive, and they will perform much better,” Byrns explains. “We are keeping the basic form of the garden, but have much more latitude.”

The future looks brighter for preserving historic gardens and landscapes. “We like to say hopefully all gardens will become historic someday,” says Winterthur’s Eirhart.