Features

NTHP Enters a New Era

By Peter H. Miller, President, Restore Media

In case you missed it, there is a new president at the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP). Her name is Stephanie Meeks. Like the endangered places her organization aims to save, Stephanie Meeks must save the National Trust itself. "The status quo is not an option," Meeks said during a recent interview.

Chartered by Congress in 1949 during the Truman administration, the National Trust for Historic Preservation's mission is to save America's places and to revitalize local historic communities. The Trust is privately funded, with 13 field offices, 300 employees and a Beaux-Arts headquarters in Washington, DC. The Trust owns 27 historic sites including the Phillip Johnson Glass House, Farnsworth and Woodlawn. All of these historic sites require maintenance and repair.

In 1966, with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act, the National Trust received federal funding. Thirty years later, in 1996, this federal appropriation was terminated by mutual agreement. By 2012, like so many nonprofits and businesses, our National Trust is facing financial challenges and has streamlined programs and improved inefficiencies, part of which includes downsizing from its current historic headquarters building to a smaller historic home suitable to the organization's current needs.

In addition to doing the right thing for our cultural heritage, the National Trust makes a market for those of us who make a living restoring and renovating historic buildings, monuments and landscapes. For example, just as the National Association of Home Builders lobbies Congress to preserve the mortgage interest tax deduction, the National Trust lobbies Congress to preserve federal and state historic tax credits, which encourage historic restoration and renovation with financial incentives for owners and developers. Likewise, just as the American Institute of Architects tells us that "design matters," the National Trust for Historic Preservation tells us that history, as expressed through our historic places, matters.

When Meeks took over at the Trust in July, 2010, she wisely declined my invitation to share her new vision for the organization. She did not have a vision yet. She spent six months "listening and learning" from partners in the field, staff, the board of trustees and other stakeholders to develop her strategy. The Trust's core values are unchanged, but the plan of action and many of the people charged with executing it are new.

At around the same time Meeks was racking up frequent flyer miles connecting with her constituents nationwide, the National Trust commissioned research to quantify the market for preservation. After several years of declining membership with a member demographic that matched the AARP's, it was time to make preservation meaningful to a broader, younger, more diverse audience. That poster child for preservation, the little old lady in tennis shoes throwing her 90-lb. body at a 900-lb. wrecking ball, had become annoying, even irrelevant.

A building's historic landmark status had become the built environment's equivalent of leprosy.

Preservation had become the movement of "NO:" you can't choose your own paint colors or widen your own back door without being obstructed by that little old lady, the historic commissioner. Along the way, preservation became synonymous with elitism.

But Meek's listening tour, supplemented by the research, gave her hope that change was possible. The research identified 15,000,000 people the National Trust call "local preservationists" with a median age of 35. This is in sharp contrast to the 250,000 members and supporters, with a median age of 51, who are engaged with the National Trust for Historic Preservation now. It would appear that the market we all serve is much bigger than we thought. There is room for significant growth.

The Trust's research identified "preservation leaders," people who are engaged directly in preservation activities and "local preservationists," those who belong to the cause without realizing it. It is these local preservationists who represent prospective members and leaders, thus the growth potential. These local preservationists frequent museums about history; stay in historic hotels; go to craft fairs; and are in some way active and engaged in community building, including the preservation of historic buildings. But they do all this on a local level, responding to something relevant in their community while not necessarily tuning in to the national message or membership solicitations from the National Trust.

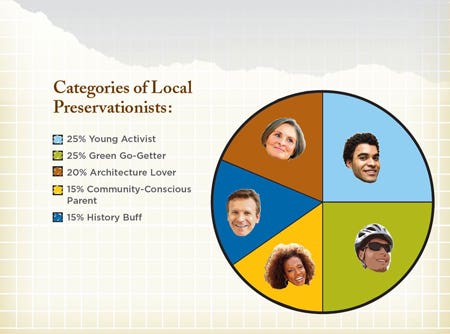

The National Trust took its research and characterized these local preservationists into five categories: young activists (25%); green go-getters (25%); architecture lovers (20%); community-conscious parents (15%); and history buffs (15%). Each has a different reason for embracing preservation. Each responds to a different message about preservation's virtues. Preservation leaders list historic preservation as their number one cause followed by environment and conservation, the arts, education-related causes, and social services. Local preservationists rank historic preservation as their number five cause, preceded by fire and police emergency rescue, disaster relief, animal welfare and social services.

Under Meek's leadership, with the help of her mostly new staff, the National Trust for Historic Preservation plans to reach out, connect and encourage these local preservationists to move preservation up their list of causes. They will do so with a strategy they call "Preservation 10X," which aims to increase the Trust's impact and scale by a factor of 10.

"The Trust must streamline and focus its programs simply to remain viable as a nonprofit in the decades ahead," Meeks wrote in a white paper titled: "Toward a New Level of Success." When she says this in person, she is measured and sincere. The Trust's core constituents, the preservation leaders in the trenches, have challenged the national organization to "engage a broader and more diverse group of people in the work of preservation – to make the movement more accessible, more relevant and better funded."

The white paper says that there are more than 100,000 private preservation groups operating nationwide. Meeks pointed out that their needs have changed and so have their expectations of what services the National Trust must provide. In a separate survey, the Trust heard from 1,000 preservation groups who asked for a higher level of assistance, including in-depth information about fundraising, federal advocacy, sustainable building and case-study success stories about saving historic places. As the preservation movement has advanced, so too have the needs of the veterans working in the movement.

Preservation 10X will build on the assumption that "preservation is most compelling when it deals in real places that demonstrate the power of preservation to contribute to communities." Think Grand Central Station in New York or the Ferry Terminal Building in San Francisco. These are important places that touch a lot of people's daily lives. "Nothing compares to the tangible experience of buildings restored, economies improved, local communities revived," says the Preservation 10X manifesto.

If saving these places is what really resonates with preservationists and prospective preservationists, then the Trust is determined to save more places. On the 25th anniversary of the "America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places" program, the Trust announced that all 11 places on its endangered list will be added this year to its new portfolio of National Treasures, critically threatened places across the country where the National Trust is making a deep organizational investment, and 100 places total by 2015. More is more. And more historic places tell a wider variety of stories; stories that embrace a broader, more diverse audience. This year's 11 Most list includes Joe Frazier's Gym, the Ellis Island Hospital Complex and the German Separatist Village of Zoar, OH. They tell an American story of cultural diversity and ethnicity.

Shortly after my interview with Stephanie Meeks, I attended the Trust's 25th anniversary party for the "America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places" program. The real title of the event was more inclusive, "Preservation Nation: a Celebration of People Saving Places." At this reception, held in the revitalized Logan Circle neighborhood of Washington DC, we heard from representatives of Popularise, a company that provides online tools for communities to crowd-source ideas for old buildings; Living Social, a hip, young, fast-growing tech company which is putting offices in historic buildings they restore; ARCH Development, a nonprofit using arts and events to draw people to Anacostia, a predominantly low-income African American neighborhood; Capital Pixel, a rendering company that uses imagery to inspire old-house restorations; the Rainbow project, which produces maps of historic walking tours that have gay and lesbian relevance; the DuPont Underground, a volunteer nonprofit group working to promote interest in an abandoned street car tunnel beneath this historic district, and PGN Architects, a firm specializing in the adaptive reuse of historic buildings.

During these presentations, I realized that I was one of the very few people over 30 years old and the only man wearing a tie. The National Trust for Preservation is trading in its musty image for a younger, cutting-edge one. Each presentation integrated the new with the old, from technology tools that help to mobilize preservation action, to young people actually doing what only 60-somethings used to do. The group was diverse and engaged. This was the Trust's new 10X strategy in action.

The approach and appeal to a wider audience is new, but the core mission of the National Trust for Historic Preservation is the same. As articulated by Meeks, it includes:

- To identify and protect America's most important and threatened "National Treasures, the "heart of the Trust's work."

- Advocate for laws, regulations and funding to support historic preservation, including the Federal Historic Tax Credits

- Support leaders in preservation with greater access to substantive information including higher-level training on fund raising, advocacy and outreach, communicated via case study success stories developed around the Trust's own sites: Lyndhurst, Woodlawn, Farnsworth and Chesterfield.

- Reach out to a broad base of supporters, the 15,000,000 local preservationists, via a new medley of communication tools such as social media and cause marketing programs.

To do all this effectively, the new National Trust for Historic Preservation will deploy resources to fewer, high-priority initiatives and eliminate some that don't make sense anymore. It will focus attention on what works and will shine a light on success stories. It is an action plan that puts limited resources to work in areas where the best return on investment can be expected. According to Meeks, "given the Trust's size and budget, the organization is unlikely to exceed four to six themes at any one time."

The initial four themes for the new National Trust will be 1) sustainable communities, 2) diversity and place, 3) public lands and 4) tomorrow's historic sites.

These priority themes will "be a filter in choosing National Treasures and will guide decisions about which advocacy efforts to undertake," she said.

Meeks and her new team believe that these themes should replace the Trust's spread-too-thin approach, to provide clarity for making communities viable, telling America's story of cultural diversity through the places that embody it, working with the federal government to preserve federally owned cultural resources, and using the Trust-owned historic sites as testing labs for new innovations in preservation practice.

One casualty of resource allocation is Preservation magazine's cut back from six to four issues a year. Now, your $20 membership fee gets you quarterly magazines plus regular emails and letters from the Trust, as well as discounts at historic hotels or sites. (As a fellow magazine publisher, I'll stick up for the Trust's decision here. Twenty dollars per year doesn't cover the cost of postage, much less the value of Preservation magazine's research, reporting and eye-popping graphics.)

Speaking of the people who make preservation happen, Ms. Meeks explained her people-approach to lobbying Congress for Federal Historic Tax Credits. Because Congress wants to raise revenue without raising taxes, Federal Historic Tax Credits are on the chopping block. So Meeks and her government affairs staff will endeavor to get more people, more stakeholders involved. This means the people who make a living in preservation and traditional building. If our business benefits from the tax incentives that make a historic restoration or renovation project viable, then we too should make our voices heard on Capitol Hill.

Chances are, with the National Trust for Historic Preservation's new and improved emphasis on outreach, inclusion and engagement, you will be hearing from Stephanie Meeks soon. Remember, if you are reading this, you are a Preservation Leader. With leadership comes responsibility. Let's help Stephanie Meeks, the National Trust and our traditional building industry move toward a new level of success. TB