Features

Helping Historic Houses of Worship

One might take as gospel the notion that historic religious buildings, from churches to synagogues to meeting houses, are sheltered from the privation and disregard that beset so many other historic structures but, sadly, this is often far from true. In some instances, the compound effects of dwindling dollars, fewer weekly worshipers and shrinking local populations are driving these huge, maintenance-heavy edifices to abandonment. Fortunately, over the years a handful of unique organizations, such as the noteworthy pioneers explored here, have devoted themselves to addressing the earthly needs of religious buildings of all faiths in some inspired ways.

Help Where it’s Needed

The problems that can plague historic religious buildings are complex, vary by locale and often have origins going back decades, but the genesis of the organizations that seek to help them is a bit clearer. “The whole movement started in the mid-1980s,” recalls Robert Jaeger, co-founder and President of Partners for Sacred Places, a national, independent non-profit based in Philadelphia. “It kind of arose in New Mexico, New York and Philadelphia first – three local programs that began in 1984 and ’85,” he says, a period that saw a lot of division in some cities between preservation folks and religious folks over the landmarking of houses of worship.

Partners, which celebrates its 25th anniversary in 2014, started in this climate as a way to fulfill the need for a national advocate and resource center for religious buildings. “In the early days we dealt with the physical issues of steeples and stained glass and masonry, which we still do address, but now we’re getting into questions of economic value and making the best use of space by matching sacred places with arts and other non-profit organizations.”

At the Sacred Sites Program of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, founded in 1986 to offer technical assistance and grants to landmark religious buildings across New York State, Ann-Isabel Friedman, director, recounts a similar, albeit regional bellwether. “In the mid-1980s there was legislative action in Albany to potentially exempt religious properties from local landmark ordinances. This became, in part, a trigger for there to be some kind of grant – an incentive or “carrot” if you will – for landmarking statewide that would counter this movement.”

The back story that Friedman explains is complex and New York-specific, but stems from the founding of the Conservancy in 1973 to provide technical and financial assistance to owners of historic properties, including grants and low-interest loans for restoration work. Unlike New York City, which has one of the earliest and strongest landmarks laws in the country, many of the historic churches, temples and other houses of worship in the rest of the state are not subject to any landmarks legislation or regulatory oversight. “Over the last 30 years,” she says, “many, many sites around New York State have sought National Register listing specifically with an eye towards potentially accessing our grant funding – and that’s the way it was supposed to work.”

Another seminal but even more specific program is the Sacred Landmarks Assistance Program at the Cleveland Restoration Society. It describes itself as an “interdenominational initiative that assists congregations … with the preservation of their historic properties.” Michael Fleenor, Director of Preservation Services at the Society, explains that “Our religious building work is mostly in Cleveland and its inner ring suburbs, though occasionally we get calls from farther out.” Here the inception is not a single event or cause celebre but the trajectory of a longstanding trend.

“Cleveland has lost a lot of population over the last 50 years,” recalls Fleenor, “and the program was, in part, a response by the trustees at the time who were acknowledging the problem and the fact that houses of worship are central landmarks in many residential neighborhoods.”

Space is the Place

Indeed, the belief that historic houses of worship are not just significant architecture but anchors in their communities, as well as for their congregations, is part of what these organizations have in common. According to Jaeger, “Our emphasis is on providing the expertise and resources that congregations need to make the most of their buildings.”

He says he often makes an analogy to the Main Street program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which assists small businesses in historic downtown buildings. “Preservation is never the first emphasis – and it shouldn’t be. For religious groups, its ministry, service and worship, so we help them see and manage their building as an asset for their larger purpose.”

Partners has long helped with fundraising, through both their staff (who conduct feasibility studies and full campaigns), as well as publications like The Complete Guide to Capital Campaigns for Historic Churches and Synagogues. However, their latest direction involves economics of a different sort. “We knew that churches, synagogues and other houses of worship were sharing their spaces – Sunday school rooms, parish halls, classrooms, fellowship halls – with lots of other entities, but typically not getting back the full value of the space in rent. In effect, they were providing a subsidy, and we wanted to get a handle on that.”

In fact, Jaeger and his colleagues learned from research conducted with the University of Pennsylvania in 1997 that 80% of the people in these spaces were not even from the congregation. “Outside of the worship day, the rest of the week these spaces serve everybody – they’re really public assets.”

What might have been a problem is in fact an opportunity. “So many churches are now so small, they have a lot of available space,” says Jaeger, so Partners now seeks to connect them to arts, foods and nutrition, and social service groups that can make a home in the building, and thereby bring revenue and new life to the congregation. As part of this new focus, Partners is working with the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to launch an online hub that allows them to inventory all the empty space that religious buildings have to offer. “It’s almost like we’re becoming, in part, a real estate entity,” he says.

The first launch into space-matching he says is the Arts in Sacred Places program. “When we started working with arts groups, we learned how often they are nomadic, going from place to place during the course of a year trying to find the next rehearsal or performance space.” He says that the holy grail is not only to connect an arts group with something they can call home for performances or rehearsals, but also to find a good user of space for the congregation. “Ideally, a theatre company, or a social services group, might have offices and storage as well as rehearsal space in a sacred place, building a real clear long-term partnership with the congregation where each can help the other meet their goals.”

Jaeger says the program is a blessing for Partners as well. “We’re attracting funding not just from preservation or religious funders, but also from foundations interested in the performing arts, because they know these small groups suffer and spend so much of their energy just finding the next space.”

Sacred and the City

If all this sounds like the proverbial working in surprising ways, it’s a pattern that rings true at the Sacred Sites program in New York. “We try to educate and connect religious properties with resources for cost-effective, preservation-minded, pro-active, maintenance of their buildings,” explains Friedman. The program acts through publications, workshops, one-on-one meetings and partnerships with regional preservation groups around the state. In fact, some of initial staff of the Sacred Sites program went on to found Partners for Sacred Places and the two organizations continue to collaborate.

Put another way, she says the program is financial services to direct projects towards a long-lived outcome. “Our aim is to provide long-term planning and incentives for activities like maintaining slate or copper roofs, which are very cost-effective over a long timeframe, but require pro-actively preparing for their renewal the day they do fail.”

While such a mandate is conceptual, it begins at a very bricks-and-mortar level. “There’s a technical focus to everything that we do,” says Friedman. “A lot of it is match-making. We talk to very small rural institutions, as well as urban ones, that have never worked with an architect or engineer before.” For example, suppose a congregation is wrestling with how to stop some active roof leaks. “Then their most immediate need is not a design architect, who might help them with space reconfiguration or accessibility, but for a construction management referral.”

She adds, “The opportunity of our grant is to provide in-person, hands-on technical assistance – and in some cases redirection.” As part of a grant review, they may go out and meet with a congregation and leadership that has, say, applied for a stained-glass window restoration, but then find that the roof is leaking and the steeple is listing. “The fact that we can reinforce our advice by helping fund the services we’re recommending is very helpful; it gives our say much more weight.” Ultimately, the program aims to help the congregation catch up on deferred maintenance and, hopefully, put them on-track to maintain their own building going forward.

Sacred Sites too recognizes the problem of under-utilized religious buildings. For example, in addition to a 2007 conference on shared space, last year they co-sponsored another conference on adaptive re-use of religious properties. “They’re challenging buildings to re-use, especially for residential conversions, which often requires subdividing really beautiful public spaces,” says Friedman, “but in New York City we’re seeing a lot of it because the real estate market will support that level of investment in housing.”

However, it’s not all bad news. Friedman describes a large Presbyterian church in Buffalo that subdivided its 1920s community wing into rental apartments via a tax-credit conversion. “The money generated from that conversion is going to allow the church to stay in the sanctuary. That kind of model can work, I think, when you have a mainline landmark that was built for 1,000 people, but the congregation, while still alive and well, is maybe 100.”

Beyond Buildings

Amazingly, these organizations have also found ways to improve the outlooks of houses of worship through the senses as well as the the spirit. “Our Arts in Sacred Places program has led us to Food in Sacred Places,” says Jaeger. “Same idea: how can we help congregations use their parish halls, kitchens, and green spaces to not just to do the traditional feeding program, but maybe grow and cook fresh, healthy, local food and include local farmers?”

He explains that traditional food pantries have often offered highly processed food – think mac-and-cheese – because it’s shelf-stable. “What the philanthropic sector wants to encourage is good, healthy food, not opening a box or can. So one of the really interesting questions coming up now is how can we honor what religious institutions have always done, but work with them to use their buildings and grounds to encourage some new dimensions to their food and nutritional ministry?”

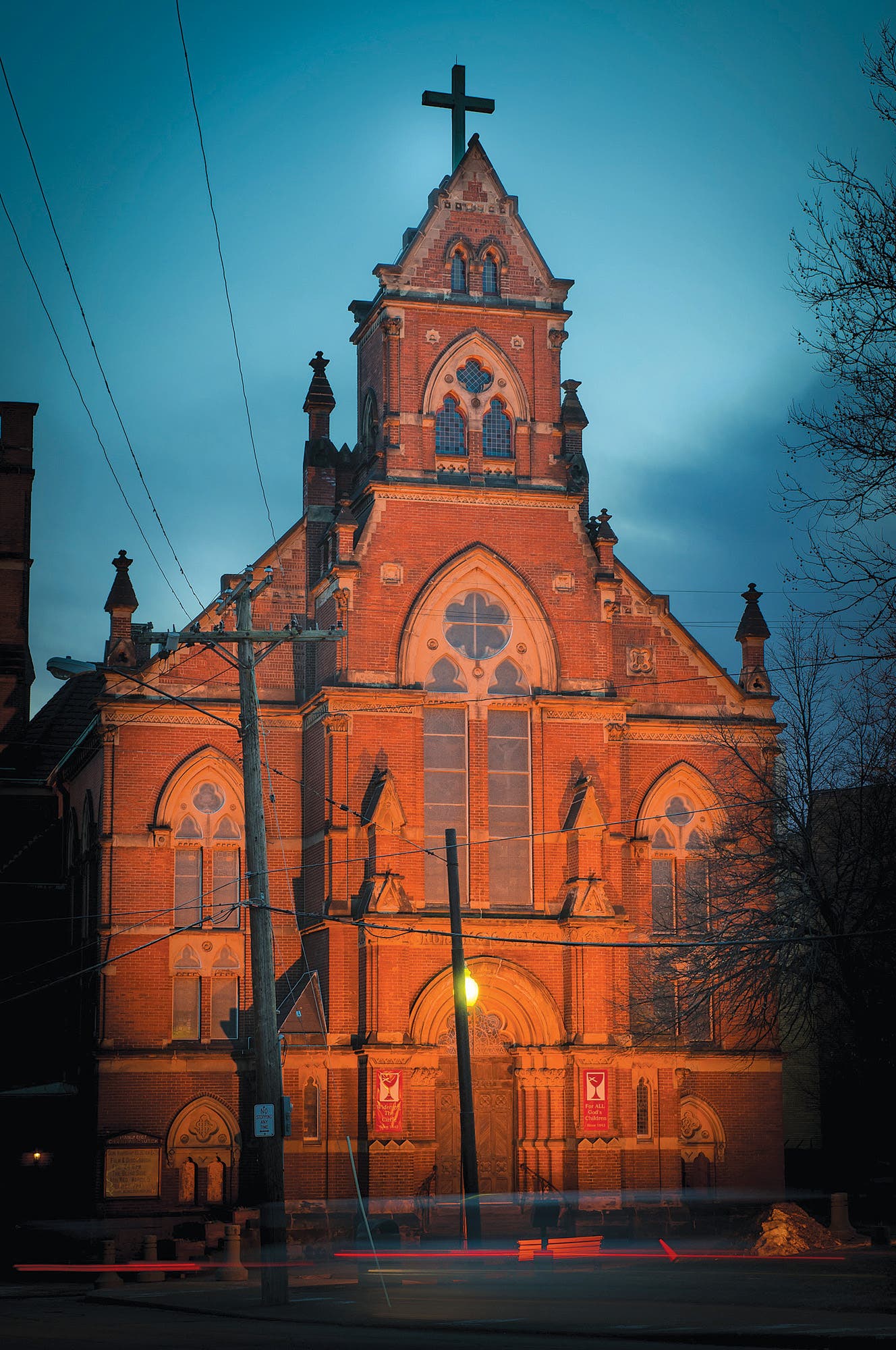

At the Sacred Landmarks Assistance Program, Fleenor describes a literally brilliant idea. “In the mid-1990s Reinhold Erickson, a dentist who lived in East Cleveland, called our office and suggested, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if anyone driving in from the airport could see all the various worship facilities lit up? You folks should be illuminating the steeples, towers, and domes downtown.'”

Fleenor recalls that, as a non-profit, his office gets many you-should-do-this-or-that calls, but about a year later unexpected news came from the Cleveland Foundation. “Reinhold Erickson had passed away, but he left a bequest to do just what he had advised, so that’s how the Steeple Lighting program got started.”

Fleenor explains that in addition to illuminating the steeple, tower, or dome, his office has an architect perform a prioritized assessment of the structure that requires completing the most pressing repairs. “It might be painting the trim or rebuilding louvers – basically tuning up the structure so that under a bright light it won’t show all these flaws.”

Erickson’s bequest helps cover the repair costs and also pays for the lighting design and installation. Sacred Landmarks Assistance also promotes the lights with after-dark trolley tours called Beacons of Hope, often with different themes. “I think in some ways it’s been among the most successful parts of our program because we have more control and, through the generosity of Mr. Erickson, the money to do the work.”

Friedman describes an initiative that is so simple it had never been considered before. “For our 25th anniversary in 2011 we launched an open house weekend – not a big advertiser-sponsored event but just inviting our constituents to open their doors at the same time.” The program lends a hand with tool kit resources for writing press releases or developing a program around a theme for the event, and the weekend is now in its fourth year across the state.

“Just opening doors, and letting people see what the church or temple looks like inside and what’s going on, is so important for building a constituency beyond your membership, and letting people know why your building should be maintained and preserved. Friedman says she’s had lots of comments like “I’ve been by this church a thousand times on a weekday, but I made the point of coming back for the tour to go inside.”

In fact, some have come from the flock themselves. “Recently we tried walking tour routes within one neighborhood where there might be three or four faith traditions within as many blocks,” she says, “which you can do pretty easily in New York City.” On one such tour of a Serbian Orthodox Cathedral, a Reformed Protestant church, and an Episcopal church, the leadership from all three later commented, ‘You know, we’ve never been in each other’s churches!’

“They’re all historic buildings, and they’re all dealing with the same issues, so the tour was almost like a support group,” Friedman says, adding, “I think that it also reminds us not only of the value of being tourists in our own town, but also to support these institutions in their efforts to maintain their buildings. We don’t want to take them for granted, because if we do, we’ll lose them.”

Some Organizations That Help Save Religious Buildings

Partners for Sacred Places

Headquarters in Philadelphia with offices in Chicago and Texas

Sacred Sites Program: The Landmarks Conservancy of New York

New York City

Sacred Landmarks Assistance Program: Cleveland Restoration Society

Cleveland, OH

Restoric LLC

Flocks in Flux

Weekly worship has been trending down in recent decades for many faith groups, from mainline Protestant denominations to historically vibrant Black churches, but the over-arching concern in many areas is depopulation. Like New Orleans, Detroit and some other older urban areas, Fleenor says that Cleveland is a shrinking city. “From a population of about a million in the 1950s, we’re down to around 390,000,” he says, adding that Cleveland and the region lost approximately 113,000 in the last 10 years.

Telling evidence is the decision by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York to merge 112 parishes, ranging from the city boroughs up through the northern counties, into 55 new parishes. “In 31 of those new parishes, one of the churches will no longer be used for regular services,” reported The New York Times in a November 2, 2014 article, “meaning those churches will be effectively closed by August.”

With building costs ever on the rise, the dwindling numbers of parishioners – and even priests – makes for dire math. “Neighborhoods in Manhattan that were once teeming with Italian, Irish, and other Catholic immigrants,” recounted the Times, “have been overtaken by office buildings and pied-a-terre for the wealthy, leaving those parishes with fewer faithful.”

Adds Neal Vogel of Restoric LLC in Chicago, “Historic houses of worship struggle with the same problems that all large assembly buildings have, including losses from changing demographics, cultural shifts, limited talent in the historic building trades, and fire.”

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.