Religious Buildings

Heavenly Designs

Ethan Anthony builds a framework for spirituality. Or at least, that’s what I envision after our nearly two-hour chat on his work for Cram and Ferguson Architects, the historic Boston firm where he is chief executive, principal designer, and president. For the better part of his career, Anthony has designed ecclesiastical buildings—churches, mausoleums, monasteries, and other church-related institutions that celebrate liturgy via architecture.

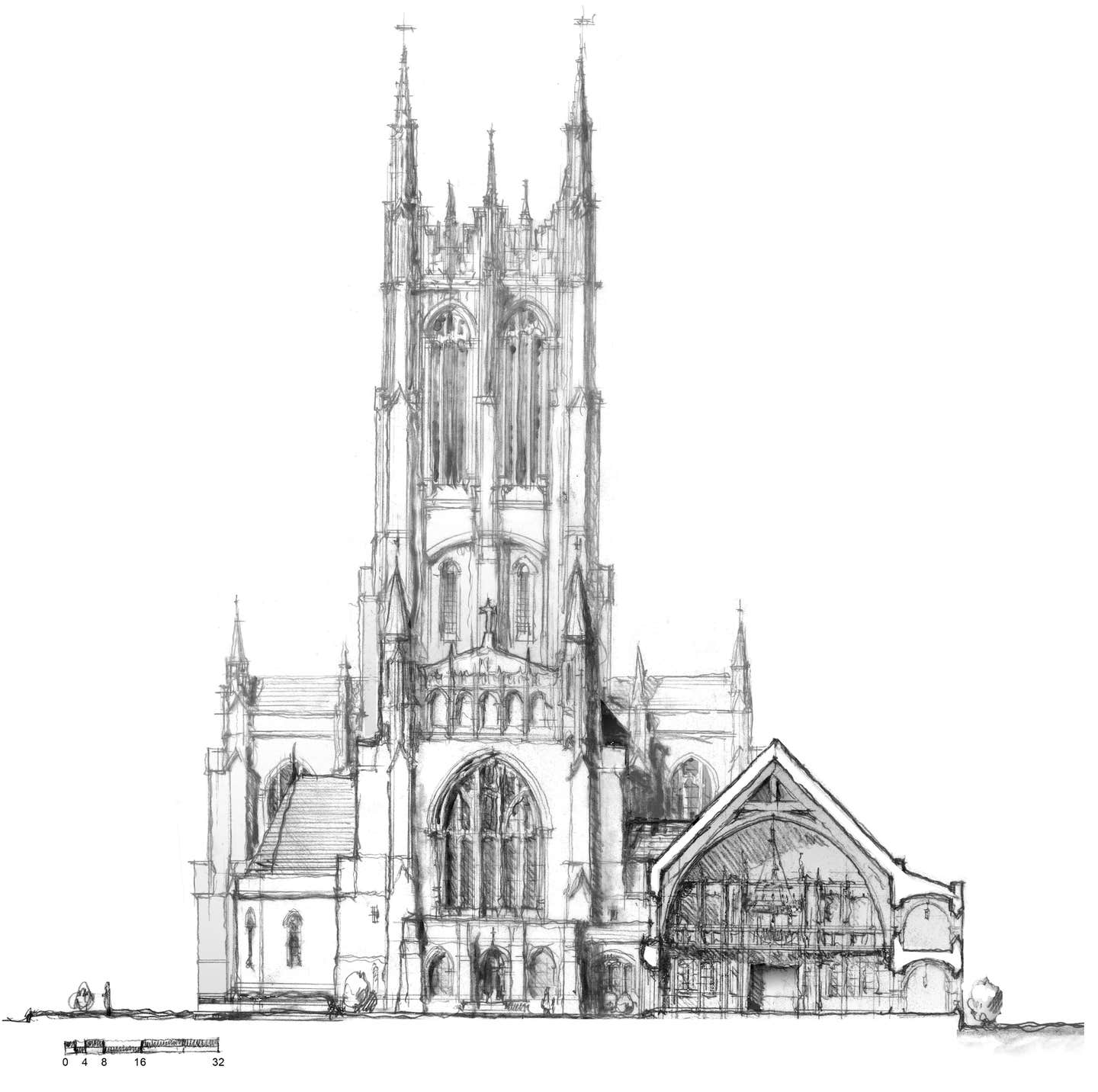

The Boston native and alumnus of the University of Oregon is an architect, a writer, and the de facto disciple of Ralph Adams Cram, the prolific American architect who worked in the Gothic Revival at the turn of the twentieth century. In fact, nearly one hundred years after Cram first ventured out into the professional world, Anthony merged his own architectural firm with Cram and Ferguson Architects. The result is a lineup of contemporary ecclesiastical monuments like Our Lady of Walsingham Catholic Church (Houston, Texas), church for the St. Thomas Aquinas University Parish (University of Virginia), Syon Abbey (Blue Ridge Mountains), and Records Mausoleum (Oklahoma City), in a showcase of how symbolism, style, materials, and craftsmanship come together for worship.

Asking Anthony about church architecture turns into a conversation about craftspeople, materials, historic churches, and of course, Augustus Pugin, the architect and writer who pioneered England’s Gothic Revival by innovating tradition. Pugin’s philosophies inspired Cram to design epic college campus building and churches, and their legacy is today’s Cram and Ferguson, which designs ecclesiastical buildings that shirk banality. It’s no coincidence that in 2007, Anthony authored The Architecture of Ralph Adams Cram and His Office.

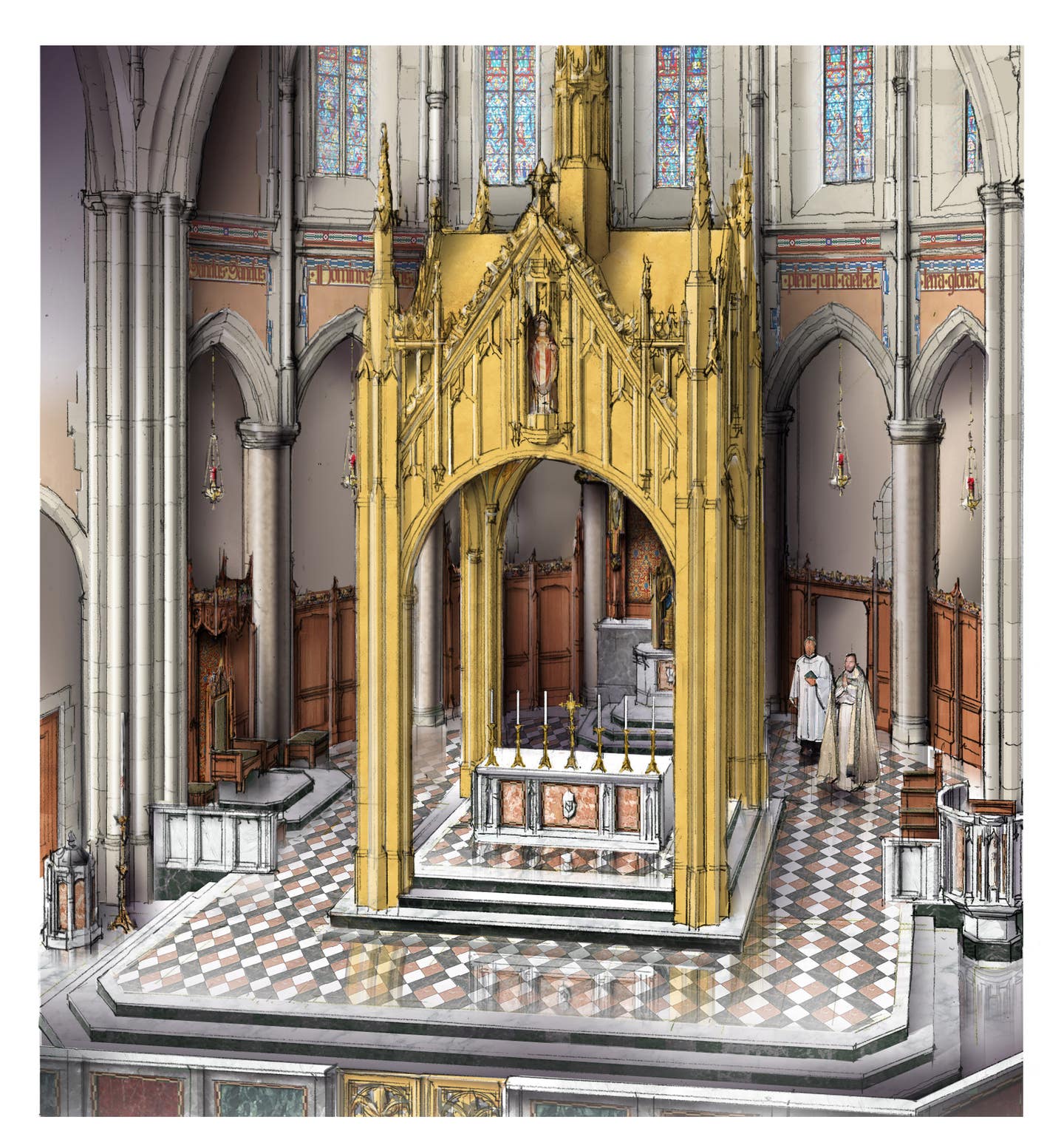

Inspiration is key to all of Cram and Ferguson’s projects, and Anthony not only finds inspiration in his firm’s storied heritage (which includes an archive of hand-rendered drawings), but also in collaboration with world-acclaimed artists, sculptors, and craftspeople as well as CAD designers, architects, and others who create every innovative detail and element, from tiny hand-carved rosettes and technicolor stained-glass landscapes to wooden communion rails and ceiling vaults.

Material is fundamental and every building is designed to last for centuries. “We [the general public] had this whole thing that happened in the ‘70s and ‘80s, where the idea was that buildings would not be permanent, that you would have infinitely modifiable structures. All that really happened was that these spaces became so ubiquitous, and so without personality and without interest that nobody wanted to be in the buildings,” says Anthony when we talk about materials and making buildings that matter. Magnificent marbles, beautiful bricks, Cram and Ferguson’s projects are designed to last for centuries.

Along with its gorgeous cathedrals and charming chapels, Europe is a landscape of tumbled church structures. And it’s those ruins, crumbled monasteries, and leftover churches that Anthony travels to explore and documents in Ruins & Rosemary, a kind of Stanley-Tucci-meets-Indiana-Jones blog. When asked what his favorite churches are, Anthony cites Milan’s brick Sant’Ambrogio and says “all of the English monasteries, many of them ruins, probably were the most important influence on me; Fountains Abbey, specifically.” Fountains was one of the world’s wealthiest monasteries until its 1539 dissolution by Henry VII, one of thousands of bankrupted church buildings left abandoned.

Prior to interviewing Anthony, I let my mind wander to all of the churches I’ve visited in the U.S. Nothing I recalled was quite as bombastic and indelible as Italian Baroque or Northern European Gothic. (Yes, there are exceptions.) I asked Anthony how he navigates that landscape of mediocrity.