Palladio Awards 2016

Schooley Caldwell Associates’ Cristo Rey Columbus High School

2016 Palladio Awards Winner

Adaptive Reuse

Winner: Schooley Caldwell Associates, Columbus, OH

KEY SUPPLIERS

Masonry Restoration: Quality Masonry Co.

PROJECT: Cristo Rey Columbus High School, Columbus, OH; James Foley, president

Architect: Schooley Caldwell Associates, Columbus, OH; Robert D. Loversidge, FAIA, Principal in Charge; Tim Velazco, NCARB, Project Architect; David A. Vottero, AIA, Design Architect; Kim Traverse, Interior Designer

Construction Manager:Corna Kokosing Construction, Westerville, OH; Jim Negron, Executive Vice President; Jim Valentas, Project Manager; Derke Erwin, Project Engineer; Dave Roden, Superintendent

Landscaping: The Brickman Group Ltd.

Plaster Restoration: Danielle Alyse

Prefabricated Gutters and Downspouts: Southern Aluminum Finishing Company (SAF)

Asphalt Shingle Roofing: GAF’s Slateline Series

Windows: Jeld-Wen’s Custom Clad Series

Exterior Doors: Jeld-Wen’s Aurora Custom Fiberglass Series

Decorative Antique Lighting:Baselite Corp.

Bronze Plaques and Decorative Interior/Exterior Signage: Columbus Sign Company

Brick Site Paving:Endicott

Brick/Sandstone Cleaning Product:Prosoco’s Sure Klean Restoration Cleaner

Limestone Cleaning Product: Prosoco’s Sure Klean Limestone and Masonry Afterwash

The Cristo Rey Catholic High School program was launched in the 1990s when the Jesuits, well known for leadership in education, saw a need for better secondary education in Chicago’s impoverished Pilsen neighborhood. They established a work-study program that helped finance the school and also provided work experience for the students.

There are now approximately 30 Cristo Rey High Schools throughout the U.S. One of these opened in 2014 in Columbus, OH, in a building listed in the National Register of Historic Places that had been derelict for many years.

The long and complicated history of this particular building goes back to 1832, when it was built as a School for the Deaf and Dumb. The name was changed to the School for the Deaf and they soon outgrew the building and built a new larger one, said to have been designed by George Bellows, Sr. (father of the famous painter), in 1868. Needing still more room, the school added an approximately 84,000-sq.ft. new building in 1899, this one designed by Richards, McCarty and Bulford.

This urban complex housed the School for the Deaf until the 1950s when the school moved to a new location. “The building underwent a series of historically insensitive renovations that significantly altered the interior spaces,” says Tim Velazco, NCARB, project architect. It was eventually abandoned and became derelict.”

When the School for the Deaf moved out, the state of Ohio occupied the lower floors in both buildings, abandoning the upper floors, until the late 1970s. Schooley Caldwell was called in to design a retirement community, a plan that was dropped when the original 1868 Bellows building burned and was demolished, leaving the 1899 building. Over the years, SCA also designed it as an office building, a plan that went all the way through construction documents; a conversion to market-rate apartments, and a children’s library.

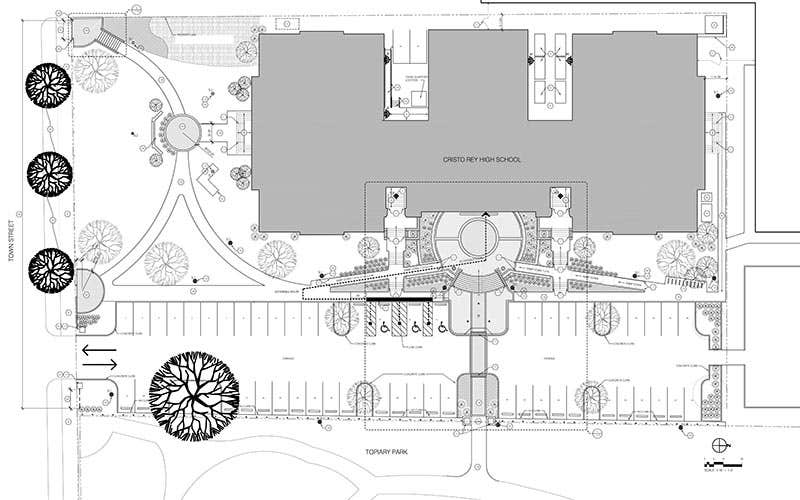

Meanwhile, the city’s Recreation and Parks Department had created a topiary garden on the site of the original 1868 building. Adjacent to the still existing 1899 building, it is based on the famous 1886 painting by George Seurat, “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte,” and has become a beloved destination point for the city.

Cristo Rey Comes Forward

In 2012, Jim Foley, president of Cristo Rey Columbus, who had been searching for a location for a school, fell in love with this building. The location was ideal: next to the library and the park, in a neighborhood called the Discovery District, which has several educational institutions, the art museum as well as the library. “The neighborhood is all about education and it is also on the bus line, for convenient transportation,” says Robert D. Loversidge, FAIA, principal in charge. “It is also in a neighborhood where they can find jobs.”

The library bought the property from the Philadelphia developer and split it, selling the building to Cristo Rey, and keeping part of the site to make a library-park connection. “Everybody won in this deal,” Loversidge adds.

This time the project would be completed. Schooley Caldwell developed a plan for converting the historic 1899, 84,000-sq.ft. building into a contemporary high school, and the new school opened in 2014, after an $18-million renovation.

The derelict structure had quite a few typical problems. The asphalt roof was beyond the end of its life and residential skylights had been added. In addition, “the interior was cheap developer stuff, with layers of carpeting and tiles, lowered ceilings and new stairs,” Loversidge points out.

“The character had been hidden or removed,” says Velazco. “Vaulted openings had been squared off with drywall and big skylights had been roofed over.”

On the first two floors, SCA created larger classrooms, taking room from the hallways. “The original classrooms were not big enough,” says Loversidge. “We created suites of classrooms by capturing some corridor space and by taking down walls between the classrooms to make large, medium and small classrooms. Elevators and restrooms were installed where the historic iron stairs, long ago removed, had been.”

One of the most significant changes was the main entry. SCA created an entry court, lowering it to make it accessible and to provide a single point of entry. “It is a shadow of the original terrace,” notes Velazco, and was created with valuable input from John Sandor, architectural historian with the National Park Service. In conjunction with the new entry and because the historic staircases had been removed long ago, they also created a new open central stairway from the ground floor to the first floor.

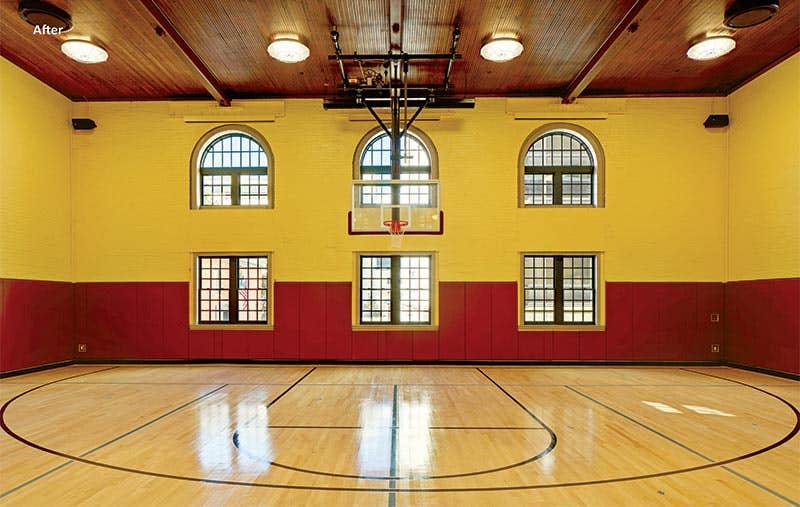

The original gym is also on the ground floor, opposite the main entrance. SCA removed a floor that had been added to the gym, taking it back to the original scale, so the gym is now open to a two-story height. They also added a large glass window on the second level so people walking by can look down into the gym.

Also located on the ground floor are the cafeteria, kitchen, storage and restrooms.

“The dormers begin on the third floor, so there are quirky spaces,” says Loversidge. “We put art, music and science up there. We could also get big spaces for specialized classrooms.”

As for fenestration, new windows with historically correct sightlines were added to replace the worn-out vinyl replacement windows. “We worked with the National Park Service to get a good match,” says Velazco. “The historic windows were long gone and had been replaced with residential vinyl windows.”

SCA also created a large, 4,000-sq.ft. chapel, keeping the columns and beams so you could see what was done.

Detective Work

Throughout the project, the SCA team investigated the building to discover and restore the historic character of the building as much as possible. “After the building had been cleared of the non-original components added throughout the years, we combed through, performing a historic inventory of all remaining character-defining original items,” says Velazco. “I like to think of this as detective work, in concept. You have to look closely for remnants of various details, collect evidence, and puzzle together what the building looked like originally. My favorite detail in the building is the chair rail, and its integration with door and window systems.”

“This was most interesting,” he adds. “When the non-original materials were gone, we found 2½-in. radius bullnose corners, and were able to replicate chair rail based on this one single detail and on scars on the walls.”

The design team also found wood floors throughout. Although the contractor initially suggested replacing it, Loversidge said they should try to restore it. “We had a great contractor who was willing to give it a try. They were astounded by how good the restored floors looked, and the cost was significantly less than replacing the flooring,” he notes. In addition, the design team found miles of wood baseboard that the contractor was able to restore and replicate in his workshop.

On the exterior, the masonry was in fairly good shape. A number of minor repairs were made and approximately 60% was repointed. A new roof – the original slate roof was long gone – was installed, the residential skylights were removed, and appropriate sheet-metal accessories, downspouts and flashing were added.

Although the building didn’t seek LEED certification, all systems are energy efficient and the building was tightened up. “The greenest building is the one that is already built,” Loversidge notes. “It is quite energy efficient, we just didn’t go through the LEED process.”

The design work started early in 2013 and construction started June of that year, and the Cristo Rey Columbus High School opened in 2014.

“All of this was made possible in part because of available tax credits (State and Federal Historic Preservation tax credits and New Market tax credits),” says Velazco. “The project came together perfectly, thanks in large part to an excellent team with a common set of goals. We are very proud of this building today."