Religious Buildings

Repairing Washington National Cathedral

Project: Post-Earthquake Restoration of Washington National Cathedral (cathedral.org), Washington, DC

Architect: James W. Shepherd, AIA, LEED, Director of Preservation and Facilities

By Martha McDonald

This year marks a significant anniversary for Washington National Cathedral—it has been five years since the 5.8 earthquake rattled it on August 23, 2011, causing $34 million in damage. The full name of this landmark Episcopal church is the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul (in the City and Diocese of Washington).

Although it is a significant date in the Cathedral’s timeline, it is one of many. The history stretches back to 1792 when Pierre L’Enfant under George Washington set aside land for a non-denominational house of prayer for national purposes as part of his Plan for the Federal City. It was over 100 years before some committed Episcopalians put forth the resources, pursued a charter and purchased land to live into that mission. Construction didn’t begin until September 29, 1907, when President Theodore Roosevelt laid the cornerstone. Bethlehem Chapel, the oldest worship space in the Cathedral, opened for services on May 1, 1912; the 300-ft. Gloria in Excelsis tower was dedicated in 1964; and the Cathedral was finally finished in 1990, after 83 years of construction, with President George H. W. Bush present for the laying of the last stone. It cost approximately $65 million to build and it weighs 150,000 tons.

The original design for the Cathedral was developed by George Frederick Bodley with his partner and former student, Henry Vaughan. Bodley died in 1907 before any construction had begun and Vaughn passed away in 1917, shortly after the first Cathedral chapel was completed. Philip Hubert Frohman of Frohman, Robb and Little, took over the project in 1921 and led the work until his death in 1972. The work was then carried on mostly according to his instructions.

The majestic 530-ft. cruciform-shaped Gothic cathedral, made primarily of Indiana limestone, is remarkable, with flying buttresses on the east and west facades, 112 gargoyles, 215 stained-glass windows, 762 boss stones, 288 angels on top of the two west towers and an organ with 10,650 pipes. The 26-ft.-dia. window, “The Creation,” above the main entry on the West Façade, is one of three such windows. This one was designed by Rowan LeCompte, fabricated by Dieter Goldkuhle and was installed in 1976.

The Cathedral has a long (one-tenth of a mile) nave, side aisles, eight bays and a five-bay chancel intersected by a six-bay transept. The 300-ft. Gloria in Excelsis tower over the transept actually reaches 600+ feet above sea level (the cathedral is on high ground), making it the highest point in Washington, DC.

The West Façade, the last portion to be completed and the main entry, features two 158-ft. 10-in. towers and three entries each topped with tympanum carvings by Frederick Hart. He also sculpted the statues of Adam and Saints Peter and Paul that greet visitors as they enter the Cathedral.

The energy of the 2011 earthquake moved through the building, releasing through the four 50-ft. grand pinnacles on the Gloria in Excelsis tower as well as through other pinnacles and roof ornament. In addition, the flying buttresses cracked. The end result was that more than 75% of the pinnacles were damaged as were many of the intricate stone carvings.

“A lot of pieces rotated, twisted and fell,” says James W. Shepherd, AIA, LEED, director of preservation and facilities. “We were lucky that no one was hurt that day. Most of the pieces fell onto the roof. Only a few pieces fell to the ground and fortunately there were no pedestrians, and visitor traffic was low because it was summertime.”

“The building is still standing and the roof is intact, but it shook and the energy released itself in the pinnacles, which are part decorative and part structural. Because it was built the medieval way—stone on stone and set with mortar—there was no reinforcement between stones. By the time we got to 1990, the west front did include some reinforcement, so it performed better during the earthquake.”

“The most visible damage was on the central tower,” he explained. “One of the grand pinnacles collapsed and the other three had to be disassembled and stabilized. They are over 50 ft. tall.”

“We had no earthquake insurance,” he adds. “It had been more than 100 years since a similar earthquake had occurred in the DC region so we didn’t imagine that we would need it.”

Repairing The Damage

The Cathedral was immediately closed after the quake, to make sure the building was safe, and re-opened on November 7, 2011. “We tried to re-open by September 11, to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of that event,” says Shepherd, “but that was not possible.” Davis Construction of Rockville, MD, was brought in as the general contractor for the repair work.

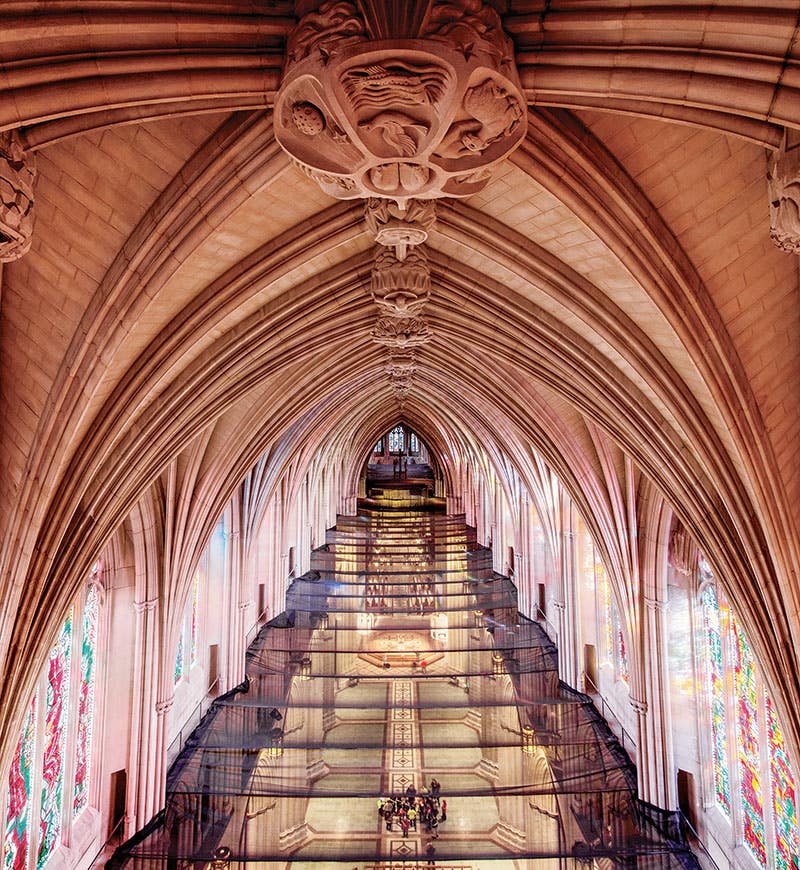

Although there wasn’t much damage to the interior, protective netting was stretched 25 feet below the ceiling immediately after the earthquake to ensure that any loose debris didn’t fall to the ground. The gothic vaulted ceiling soars 100 ft. above the nave floor. “Of the $34 million needed for repairs, we were able to raise $10 million,” Shepherd notes. The first $2 million was spent on stabilization, including the protective netting.

The next step was analysis. Because there had been so many designers and contractors involved with the construction of the Cathedral over the years, there were no accurate “as-built” plans or documents for the building. “So we had the building scanned by Direct Dimensions, Inc., a laser scanning specialist with heritage documentation expertise. There were 890 individual 3-D scans—and these were translated into very accurate electronic elevation and floor plan drawings that we could use to plan for repairs,” he adds.

Shepherd and his team focused on the inside first. Scaffolding that didn’t come all the way to the ground allowed the work to continue without interfering with the worship services. “We worked with Safway Services, the scaffolding subcontractor who recommended the use of an existing ledge at the clerestory level on either side of the nave about 65 feet up to span across with lightweight trusses. A platform was built on the trusses and from there additional fixed scaffold was constructed that reached to the height of the ceiling,” he explains. “Lorton Stone, the masonry sub-contractor, was able to clean, repoint and repair all of the stone of the high vaulting. At the same time, while the scaffolding was in place, we cleaned all of the stained-glass windows at the clerestory level. It is now very bright and beautiful.”

Then they turned to the exterior. The first goal was the east end, the oldest part of the cathedral, where six flying buttresses had been damaged. Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates Inc, the project engineers of record, was brought in to engineer the repairs of buttresses and add seismic reinforcement. Davis Construction subcontracted Masonry Solutions International, Inc. to drill horizontally through the buttresses (a distance of about 22 ft.) and 3 in. into the side of the cathedral. Stainless steel rods were then inserted and grout was injected to provide additional strengthening.

A similar type of reinforcement was added to the pinnacles, except that they were drilled vertically. The pinnacles were first disassembled and then restacked with the stainless steel center cores. Stainless steel anchor pins were also added to resist potential rotation. “Earthquakes cause back and forth movement that rocks the stacked stones which in turn can rotate. The pins and center core help resist these movements,” Shepherd says.

“The initial funds we raised got us to June, 2015, the end of Phase 1,” he notes. “We broke Phase 2 into 9 sub-phases.” While they were strategizing about which sub-phase to start next, a piece of the building fell off from the north transept in March of 2015. “This prompted us to begin Phase 2a at this location. When we got up there, we realized that there was quite a bit of damage; we were fortunate that more pieces hadn’t fallen.”

The Cathedral’s head stone mason, Joe Alonso, and two stone carvers that work for the Cathedral, (Andy Uhl and Sean Callahan) have helped to complete these repairs.

With a nod to the 21st century, these pinnacles were re-carved robotically by Easy Stone Center of Vienna, VA. “We had Easy Stone carve the pinnacles to 75% completion and then the Cathedral’s stone carvers do the remainder of the finish work,” says Shepherd. “This was a very good marriage of technology and craft, and it saved us a lot of time and money. We can continue to say that all of the stone on the outside of the Cathedral is hand carved and unique.”

“We are now strategizing as to where to focus our energy next,” Shepherd says pointing out that only 13% of the exterior repairs are completed. “The Cathedral doesn’t get any government funding—we are dependent solely on private donations, so we anticipate that it could take a decade to raise the funds and complete the repairs. It took 83 years to build the cathedral; hopefully, it won’t take 83 years to restore it.”

Key Suppliers

General Contractor: Davis Construction, Rockville, MD

Laser Scanning Specialist: Direct Dimensions, Inc., Owings Mills, MD

Engineers: Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Northbrook, IL

Masonry Subcontractor: Lorton Stone LLC, Springfield, VA

Stone Carving: East Stone Center, Vienna, VA

Cathedral Stone carvers: Joe Alonso, head stone mason; Andy Uhl and Sean Callahan, stone carvers