David Brussat

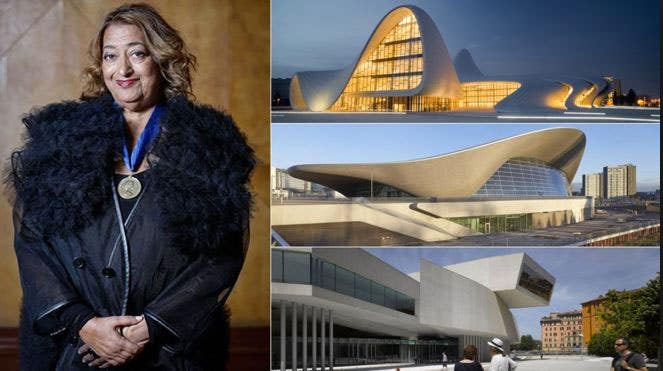

Walking in Modernist Shoes: Zaha Hadid

A passage I cannot now locate in “Master and Commander,” by Patrick O’Brian, has ship’s surgeon (and Admiralty spy) Stephen Maturin urging Captain Aubrey to “walk in the other man’s shoes” before leaping to criticize. When architect Zaha Hadid died the other day, I tried to walk in her shoes. They did not fit.

Speaking of shoes, Hadid in her time designed a few pair. Her most celebrated shoe could as easily be, were it larger, a Hadid building – space for a foot on the inside and a shiny metal thingamajig on the outside, looking as far from a lady’s shoe as possible. Her buildings all have doors, and interior spaces from which one may ignore its exterior – as Guy de Maupassant dined at the Eiffel Tower to avoid looking at it. These are the only concessions to tradition in her entire oeuvre.

In a post I wrote after she died, I was able to summon the reserve to wish her rest in peace. I cited Hadid as a model to fellow modernists and women in architecture. Still, I could not bring myself to praise her work. So to avoid speaking ill of the dead, I spoke ill, very ill, of her industry, and wished that her death might inspire its practitioners to introspection. But walk in her shoes? I will try again.

Modern architects seek to achieve a purity of line, and are willing to follow that line wherever it goes. Form follows function, function follows form, however you say it, it makes sense. Turn it upside down or inside out, it is the perfect modernist credo, which only suggests the banality of the famous line from Louis Sullivan.

In spite of his work’s embrace of profuse ornamentation, Sullivan is now deemed “a precursor to modernism” by architectural historians. How can modernists consider Sullivan one of their own? Is it solely because he said “form follows function”? Increasingly I must conclude that the answer is yes. But forgive me, I am falling behind in my effort to walk in the modernist’s shoes.

It is a daunting task. To walk in the shoes of another would seem to imply a specific path to follow, yes? But aside from having doors (however well hidden) and windows (however difficult to open), modernists try to design buildings that follow no aesthetic precedent. At the top of their profession they are pure egoists, carving out styles by which to sell themselves; down below, quotidian modernists try to establish their claim to the unique by disguising their reliance on precedent.

I just trolled BrainyQuote.com in search of a quote establishing the modernist belief that an architecture “of its time” must reject precedent, which is the essence of timelessness. I found nothing. Oddly enough, however, going through all those quotes, timelessness seems to be the main goal of modern architecture. Either its practitioners are in denial or they don’t know (or care) what the word means.

The abhorrence of precedent distances modernists from timelessness, but also from genuine creativity. In 1914, at about the same time that Adolf Loos was declaring ornament a crime, Geoffrey Scott wrote The Architecture of Humanism, his only book on the subject. He made the case for precedent as key to innovation:

[I]t should be realized that a convention of form in architecture has a value even when it is neglected. It is present in the spectator’s mind, sharpening his perception of what is new in the design; it gives relief and accent to the new intention, just as the common form of a poetical meter enables the poet to give full value to his modulations. So, in Renaissance architecture, a thickening of the diameter of a column, a sudden increase in the projection of a cornice, each subtlest change of ratio and proportion, was sure of its effect. … Certainly every deviation must justify itself to the eye, and seem the result of deliberate thought, and not of mere ignorance or vain “originality.” But deviations, sanctioned by thought and satisfying the eye, are the sign of a living art.

Put that in your shoe and smoke it, Zaha Hadid, as you rest in peace.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.