Projects

Private Garden Goes Public

PROJECT

Greenwood Gardens, Short Hills, NJ

ARCHITECT

Historic Building Architects, LLC, Trenton, NJ; Annabelle Radcliffe-Trenner, AIA, RIBA, LEED AP, principal; Sophia Jones, Assoc. AIA, project manager

Landscape Architect

Rodney Robinson Landscape Architects, Inc., Wilmington, DE; Rodney Robinson, FASLA, LEED AP, principal; Allan Summers, PLA, LEED AP, Associate; Jonathan Ceci, PLA

General Contractor

Masonry Preservation Group, Merchantsville, NJ

By Martha McDonald

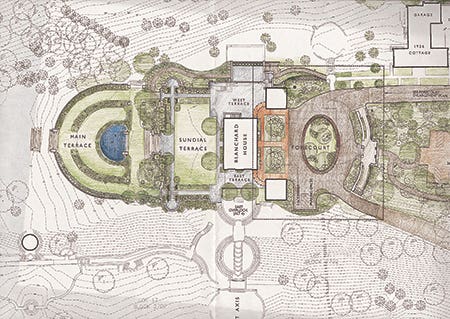

Greenwood Gardens in Short Hills, NJ, is a 28-acre historic garden filled with rustic paths, pools, cascades, exedras, pergolas, walks, terraces and grottos as well as a number of built structures and a Colonial Revival residence. It welcomes thousands of visitors every year. But it wasn’t always that way; until 2011 it was a private garden.

The first chapter in the garden’s history unfolded in the early 20th century when self-made millionaire Joseph P. Day retained William W. Renwick to design his 70-acre estate in Short Hills, NJ, as a refuge from the city. Completed in 1911, it was called Pleasant Days, and included not only the gardens, but also a gilded age mansion. It was a masterpiece of plantings and buildings in the Neoclassical style blended with Arts and Crafts touches.

Pleasant Days was in its heyday in the 1920s and 30s. When Day passed away in 1944, the property was divided and sold at auction. In 1949, Peter P. Blanchard, Jr., and his wife, Dr. Adelaide Childs Frick, purchased the house and gardens. They replaced the original mansion with a smaller Colonial Revival brick house, changed the name of the estate to The Greenwoods, and added different plantings over the years.

When Peter Blanchard, Jr., died in December, 2000, his son, Peter P. Blanchard, III, decided to donate the estate to the public, following his father’s wishes. He turned to the Garden Conservancy, a national organization based in Cold Spring, NY, to guide the transition. Greenwood Gardens is now open to the public as a garden and a center for the study of nature, historic preservation and conservation.

The transition from private to public required quite a lot of planning and work.

Historic Building Architects, LLC, of Trenton, NJ, and Rodney Robinson Landscape Architects, Inc., of Wilming-ton, DE, were hired to restore the gardens and convert them into a public facility.

“We did an assessment of the built features,” says Annabelle Radcliffe-Trenner, principal, Historic Building Architects, LLC. “Renwick was an architect, so it was really a built landscape. The issue was how to transform it from a private to a public garden, while respecting both styles and showing the development of the garden. The Day era represented the gilded age while the Blanchard era moved the gardens into the Colonial Revival style.”

“There were a lot of landscape issues,” she explains, “such as how to get the public into the site, how to give a good arrival experience, how to handle buses, circulation issues, providing lighting for events, safety issues. For example, some of the walls were low, so how do you keep the public safe? We added plantings and removable handrails.”

“Preservation and conservation were established as the primary goals from the beginning,” Radcliffe-Trenner notes. “Land conservation and sustainable design solutions were important considerations.”

“This was a comprehensive first-phase project,” says Allan Summers of Rodney Robinson Landscape Architects. “It’s always a challenge to transition from a private estate to a public garden while being mindful of the historic nature of the place. It’s a wonderful story. When we came to the project, the garden was in a state of disrepair and had become overgrown, which is not unusual with old estates. The owners, the Garden Conservancy and Greenwoods’ staff have been extremely supportive. It was their dedication that made the project move forward.”

One of the first issues addressed was the traffic pattern. “We had to widen the entrance to the site and the drive, as well as design new parking to accommodate visitors,” Summers notes. “The forecourt was redesigned to provide a visitor drop-off area and entry walks to the gardens and visitor services. Existing sculptures, such as antique terra-cotta lions, were incorporated into the design. We used an element of the original forecourt design to recreate a raised oval planting bed edged in boulders and transplanted mature 30-ft. hollies to this location. The entry garden is a somewhat formal design with a limited plant palette in keeping with the Colonial Revival house, while the surrounding gardens are more exuberant, reflecting the Italianate Arts and Crafts heritage.”

He points out that much of first-phase restoration is underground. All of the site utilities were significantly upgraded. New electric lines, lighting, water and sanitary lines and storm water management were all added. “The Blanchards had been operating on well water,” says Radcliffe-Trenner. “We worked closely with the engineers to bring in these lines.”

Parking was provided by paving the old tennis court. A garage on the west side of the Blanchard house was converted into public restrooms. As for lighting, Summers explains that poles were installed within a row of existing conifers so they would be inconspicuous when not in use.

Also important, and perhaps more visible, was the restructuring the gardens to the rear of the house, including the Sundial Terrace and the East and West terraces, and editing and updating plantings. “The whole area to the rear of the house was completely dismantled,” says Summers. “Walls were rebuilt, paving redone and pergolas were restored. Fortunately, there were detailed archival photographs to guide us.”

The pergolas in the Sundial Terrace during the Day era had been removed during the Blanchard era, but two were reconstructed based on archival photos. These are located in the east and west corners of the terrace, and are adorned with hand-crafted copper masks of rams, also following historic photos. Two historic masks were also recreated and the beams are topped with rustic, hand-hewn Alaskan white cedar purlins.

The retaining walls throughout the garden were a particular challenge.

They had disintegrated over the years, and Renwick had designed them so that each wall was tapered at a slightly different angle, to create different perspective views. The architects sought to restore these original architectural proportions using 3-D survey data. Also restored were the benches that were built into the walls and the exedras near the pergolas.

New precast paving stones in the terrace represents the Day era in the pergolas with bluestone paving representing the Blanchard era elsewhere. “This was done to show the development of the garden,” says Radcliffe-Trenner.

Barrier-free access was provided to areas throughout the site by reconfiguring pathways and stairways. “The entire upper terrace is now barrier-free and a new path has been designed to the west to provide access to the lower main terrace,” Radcliffe-Trenner points out.

A large number of different Rookwood tiles found in one of the grottos, were restored and replaced as needed. These included designs of Pan and Dionysus, shells, leafs, balls and squares; they were carefully documented, removed, preserved and replicated by Temple University’s Tyler School of Art Ceramic Studios.

The work was made more difficult by the location of the gardens on a narrow ridge. For example, all equipment had to be brought in from Short Hills Road to the buildings and gardens, a distance of 2,000 ft. It also meant that various plantings had to be temporarily relocated and conserved during construction. Radcliffe-Trenner adds: “Local planning ordinances and safety and access for emergency vehicles had to be considered. All had to be designed while keeping the feel of a private and beautiful garden.”

“Using photos taken during the Day era of the 1920s and 30s, we were inspired to design plantings in the spirit of the era, but with a contemporary sensibility and maintenance requirements,” says Summers.

“The intent was to capture the exuberant spirit of the Day era without confining the selection to heirloom plants,” he adds. “New types of plants, cultivars with desirable attributes and modern selections with superior disease resistance were chosen to provide a sophisticated palette throughout the growing season. The woodland was planted with a mix of native trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants.”

The New Jersey Historic Trust provided a significant preservation grant for this $5-million, 2½-year project. The 28-acre garden is now open to the public and its future has been secured. TB

Key Consultants & Suppliers

Structural Engineer:

Sillman, New York, NY

Mechanical Electrical Engineer:

Princeton Engineering Group

Princeton, NJ

Civil Engineer:

Maser Consulting, Hamilton, NJ

Architectural Precast:

Sun Precast Co., Inc., Beaver Springs, PA

Concrete and Carpentry:

Gaul Construction, Inc., Burlington, NJ

Historic Tile Conservator:

Materials Conservation Co.

(Formerly Milner & Carr Conservation, LLC) Philadelphia, PA

Stucco & Plaster Contractor:

Four Leaf, Inc., Bensalem, PA

Ornamental Copper:

European Copper Specialist, Inc. Newark, NJ

Plumbing & Mechanical Contractor:

Hammond Contracting Co., Inc. Lebanon, NJ