Features

Christine G. H. Franck Receives Clem Labine Award

By Gordon Bock

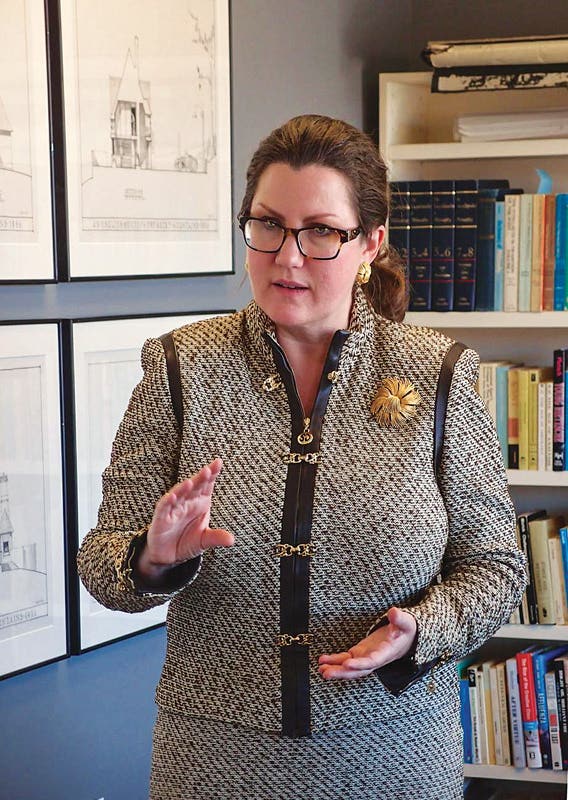

Sometimes, words do have the power of actions, as when they’re charged with the zeal of the traditional architecture gospel. By virtue of her demonstrated commitment – both professional and personal – to infusing humane values into architectural education, Christine G. H. Franck (http://www.christinefranck.com) is the 2016 recipient of the Clem Labine Award. “Christine is a tireless networker,” explains Clem Labine, founder of Traditional Building and Period Homes magazines, “[who] through her writing, teaching, and public speaking, has stressed to both students and practicing professionals alike that architecture is a public and social art.”

In contrast to a design award that acknowledges an exemplary building, the Clem Labine Award, which began in 2009, publicly honors an individual’s personal achievement. “The winner of the award is always an outstanding example of a life with a purpose,” says Labine, “given to a person who, over an extended period of time, has demonstrated both professional and personal devotion to creating a more humane and beautiful built environment.”

If a life-labor of preaching architectural education sounds comparable to a calling, the likeness is not far-fetched. “I think when you’re mission-driven,” says Franck, “what you really want to see is change, is impact – whether it’s in work as a designer or as an educator.” Labine, who has known Franck for 25 years, calls her a “missionary for the classical tradition.”

Indeed, over a career that began with architectural degrees from the University of Virginia and University of Notre Dame, Franck has more than once converted from designer to academic, often helping to create whole new educational venues – and for whole new organizations. The words first and founding surface regularly in her CV.

An early example is a set of seasonal programs that turned out to be an epiphany as much for Franck as for the students. In the latter 1990s, while working in the office of noted classical architect Allan Greenberg in Virginia, Franck got word that the then-named Prince of Wales’s Institute of Architecture wanted to start a summer program in the U.S. – and with it an opportunity to develop and run the school. “I jumped at the chance,” she recalls, “and scrambled around to put a proposal together.” Ultimately, she worked with the director of the program, Dr. Richard John, to administer a two-month course of study, which in turn opened doors to teaching a studio in Rome the next year for Notre Dame, followed by administering a second American summer program for the Prince of Wales’s Institute. “In a roundabout manner, this is how my career shifted from a primary focus on practice to a primary focus on education,” she says.

Learning from a Landmark

In a way, the course for Franck’s ‘Life with a Purpose’ was set at an early age – so early, in fact, she had yet to drive a car. “I grew up in Williamsburg, Virginia (the city that includes Colonial Williamsburg) and, as a child, I thought that was the kind of world that most people lived in – where you could walk or ride your bike downtown or go to a small grocery store.”

She says it was a world filled with beautiful buildings, in a town plan that’s laid out in a way that makes its political logic clear. “It’s everything that traditional architecture and urbanism is good at producing.” However, when Franck later moved to the 1980s suburbs of northern Virginia and then began to study architecture, she sensed something was wrong. “We lived in the worst suburban sprawl where I had to drive everywhere. My father got up at 4:30 AM to commute to work. It radically changed me.”

While completing her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Architecture, she set herself on a path of self-education that included working at firms like Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company and Allan Greenberg, LLC. “Moving on to graduate school and working, I became aware that there were other people like me, and that there was a lot more to learn about how to make good places – that, in fact, we used to know how to do it very well.”

She says she began to link up with this broad network of people who, at this stage, were just starting to find each other and connect the dots by forming organizations, such as the Institute of Classical Architecture (now ICA&A). Franck came to the fledgling organization when it was about five years old, first with a stint as Executive Director, and then through a succession of roles where needed.

“I was first put on our Advisory Council, and then joined our National Board, from 1998 until 2010,” she says. Over the course of that tenure, Franck helped grow a variety of educational efforts that included summer programs, continuing education programs, and salons. “I continued the pattern that the Institute already had, but then added things, such as when Richard Cameron and I developed the Rome program, the Institute’s first travel program.” This program has become a series that now goes all over the world. “Through the academic programs committee that I chaired, we developed a really robust continuing education program that now runs on a regular basis, including offering a certificate from the Institute.”

In the mold of many true-believers, Franck is a classic self-starter. “I would say my work always has the same inspiration: If I see something that needs to be done, I try to do it myself, or figure out who can.” As an example, Labine cites developing ICA&A tutorial seminars in association with the American Institute of Building Designers as one of her outstanding achievements. “This pioneering program exposed several hundred residential designers to the theory and principles of classicism,” he says.

In fact, Franck describes realizing that two attendees for a New York continuing education class, Bud Lawrence and Bobby Morales, were actually from Florida. “Are you two really flying up here for classes three weekends in a row?” she asked. When they answered, “Yeah, because we really need to learn this, and all our guys need to learn this, and you’re the only people teaching it,” she took it as a sign. “Out of that conversation, the ICA&A hatched the idea of developing a program specifically for home builders and residential designers in Florida to help them learn about different American architectural traditions.”

Where No Traditionalist Has Gone Before

For Franck, the process of growing architectural education programs has itself grown into something more. “There’s the direct educational work, in terms of developing new programs, teaching them, staffing them, and working with students,” she explains, “but then there’s the non-profit work of helping to develop organizations like the ICA&A,” She says she learned so much from service to the ICA&A (“I think I’ve been on just about every board committee we had.”) that, using the same kinds of models, she’s been able to help other organizations, such as INTBAU (International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture & Urbanism).

“INTBAU is an international organization that promotes the social and civic benefits of the world’s varied architectural traditions,” explains Labine. “Christine’s pro-bono work with INTBAU has extended her influence beyond the U.S. borders, and her outreach work there has helped advance the cause of classical and traditional design on both sides of the Atlantic.” As she explains, early on in its formation, among other activities, she helped advise the set-up of INTBAU’s chapters, which now number some 22 around the world. This summer, 2016, Franck will be in Sweden for INTBAU’s first summer program.

Ever eager to take on a challenge, in 2013 Franck joined the College of Architecture & Planning at the University of Colorado Denver in order to create the new Center for Advanced Research in Traditional Architecture (CARTA). She currently serves as its first Director. “It’s not only a culmination of everything I’ve been doing so far,” she says, “but also I think it’s where we need to see the most change in terms of helping schools of architecture engage with and learn from the past.”

Says Labine, “Her work at CARTA will help shape architectural education for years to come.” The center has to be self-funded, says Franck, “And thanks to a kind gift from the Driehaus Charitable Lead Trust and our founding sponsors, we have our basic operational costs covered for a three-year period.” But being a challenge grant means she still has to raise additional funding. Nonetheless, Franck has made good use of her resources, awarding some $30,000 worth of scholarships in the last three years and launching the College’s first Career Fair program.

The fair, which started with 12 traditional architecture firms, now features about 50 firms and involves the whole college. “For me, both my paid work and my pro-bono educational work have the same focus,” she says. “It’s making sure that we provide opportunities for students, architects, and anyone else who wants to learn about traditional architecture -- what it is, how you make it, and why it’s beneficial.”

Previous recipients of the CLEM LABINE Award

Alvin Holm, Alvin Holm A.I.A. Architects

Steven W. Semes, Professor and Director of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation, University of Notre Dame School of Architecture

Ray Gindroz, cofounder of Urban Design Associates (UDA)

Jean Carroon, FAIA, LEED, Principal for Preservation Goody Clancy

Milton W. Grenfell, Grenfell Architecture

Robert Baird, Vice President, Historical Arts & Casting

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), lists his fall 2016 courses, seminars, and keynote addresses at www.gordonbock.com.