Features

Preserving Detroit’s Future

The City of Detroit has had more than its share of big, bad headlines in the last few years, but the bigger news is that not only is the greater downtown area rising like a phoenix but that its renewal is, in large part, being fueled by the old. Iconic skyscrapers, along with bread-and-butter office and factory buildings, are being transformed into apartments, hotels, chic shops and entertainment venues that are bringing in a new generation of employers and reverse-commuting residents to the once downtrodden city.

These projects form the backdrop for a wider revival that includes a streetcar line, a bridge across the Detroit River to Windsor, Ontario, and a 44-block arena and entertainment district. “This is the dawn of Detroit’s next golden age,” declares developer David Di Rita, principal of The Roxbury Group, which was founded in 2005 and has been working in the city since then. The so-called Renaissance City is in the perfect place and perfect time for a revamping. The story, appropriately enough, starts and ends with architecture.

Founded in 1701 by the French trader Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, Detroit came into its prime as a mercantile center in the 19th century, and the Gilded Age structures it erected reflected its power and prowess. The oldest, 1895s United Way Community Services Building, soon was joined by an illustrious set that included Detroit Cornice and Slate (1897), the Romanesque Globe Tobacco Building (1888) and the Wright-Kay (1891).

The automobile-fueled building boom all but put them in the dust, adding a constellation of Art Deco and Neoclassical spectacular structures by the likes of Daniel Burnham, Albert Kahn, Louis Kamper and Smith Hinchman & Grylls that still define its mighty Midwest skyline.

Burnham’s Ford (1909), Dime Building (now Chrysler House) (1912) and David Whitney (1915) led the way for Kamper’s Book Cadillac Hotel (1924) and Book Tower (1926); Albert Kahn Associates’ Cadillac Place (1923) and Fisher Building (1928); Writ C. Rowland’s Gothic Revival Buhl Building (1925), Penobscot (1928) and Guardian (1929); and John M. Donaldson’s David Stott Building (1929). During the succeeding decades, other buildings by other architects rose, but, for the most part, they were eclipsed by these historic gems.

The city’s fortunes continued to rise and fall with those of the rest of the nation, and by the turn of the 21st century, the Motor City had sputtered to a halt. Unlike some other cities that scalped their skylines to modernize, Detroit pretty much left things alone simply because few were willing to invest in what was perceived as its bleak future.

Ghost Town

The city became a ghost town. People and businesses moved to the suburbs; buildings, last renovated in the 1960s and early 1980s, became vacant and derelict. The population dwindled from a peak of 1.8 million in 1950 to 700,000 in 2010.

There was a pre-existing preservation movement afoot, and by the 2000s, adaptive-reuse and rehabs, most notably the redevelopment of the Book Cadillac Hotel, which had sat dormant for 25 years, were in the pipeline. However, the 2008 recession slowed that momentum.

In 2010, Detroit native Dan Gilbert, the owner of Quicken Loans, stepped in, and as he said, in 2013, the year the city declared its spectacular bankruptcy, “went on a skyscraper sale.” To date, according to the headlines, his Bedrock Real Estate arm has restored not only some 78 properties that total 12.5 million square feet, but also the city’s faith in itself.

News stories tend to focus on him but there are others, including The Christman Co., Quinn Evans Architects and The Roxbury Group, also working on major projects, even some of Bedrock’s. “Developments were slow and steady before the crash,” says Elisabeth Knibbe, FAIA, LEED AP, principal of Quinn Evans Architects, which has an office in Detroit. “He gave it legitimacy.”

And publicity.

“What’s going on in terms of preservation and adaptive reuse has happened in other cities,” Di Rita says. “In Detroit, it’s seemingly all at once, but it’s the full flower of what’s been under way for a long time.” The adaptive reuse movement that’s making Detroit a vibrant 21st-century city center cannot be easily duplicated in other cities, largely because, unlike the Motor City, most of their historic buildings have not survived intact.

“Whenever Detroit had resources, it, like other cities, tried to tear buildings down and start over,” Di Rita says. “We did lose some buildings, notably the Detroit Statler Hotel, the J.L. Hudson Department Store and the Lafayette, but the reality is that Detroit was an accidental beneficiary of its own lack of resources. There was no money to tear down the buildings. The result is that, today, outside of New York City, there’s no better collection of early 20th-century high-rises.”

And, he adds, there were few cities prosperous enough in the 1920s to build on such a grand scale in such a short period. “Detroit’s skyscrapers are a manifestation of a moment in time,” he says.

Knibbe agrees, adding that “no other city has the same fantastic stock of early 20th-century buildings in its downtown core. We lost a lot, but we kept more than we lost, and we have some of the best skyscrapers in the country.” The fact that many of Detroit's historic buildings are abandoned is an asset, she says, because they offer an “open opportunity for sustainable solutions. They are shells, so they’re easier to convert than those with intact historic architectural details.”

She points to the Garfield Manor Apartments at 71 Garfield Ave., which her firm recently converted to a green office and residential space. “An old tenement, it was vacant, a fire victim and beyond redemption,” she says. “We turned it into an almost net-zero-energy building.”

Tax Credits

While other cities have spurred preservation with tax credits, Michigan’s historic tax credits ended in 2011, and most of the projects have been forced to rely solely on the 20% federal rehabilitation tax credit. Before the state credits ended, the residential David Broderick Tower (1928) was renovated in 2013; the Garden Theater in Midtown (1912) was repurposed in 2014; and the David Whitney was converted from medical offices to residences and a hotel in 2015.

The Garden Theater, a Quinn Evans project, is representative of the city’s focus on creating attractive mixed-use projects. The C. Howard Crane structure, built as a neighborhood movie theater in 1912, was restored and parts converted to conference rooms and office space. An adjoining storefront houses a new restaurant, and another storefront houses a café. The new building fills a gap between the historic storefronts, and the Woodward Garden Apartments fill out the south end of the block. “This was the worst block on Woodward; it was like Skid Row,” Knibbe says. “The project encompassed three historic buildings, two new buildings and a parking deck.”

It is projects like these that are bringing in young people, who like to frequent brew pubs and tony shops like Shinola, the watchmaker that rehabbed the old Creamery Building on Selden Street in Midtown.

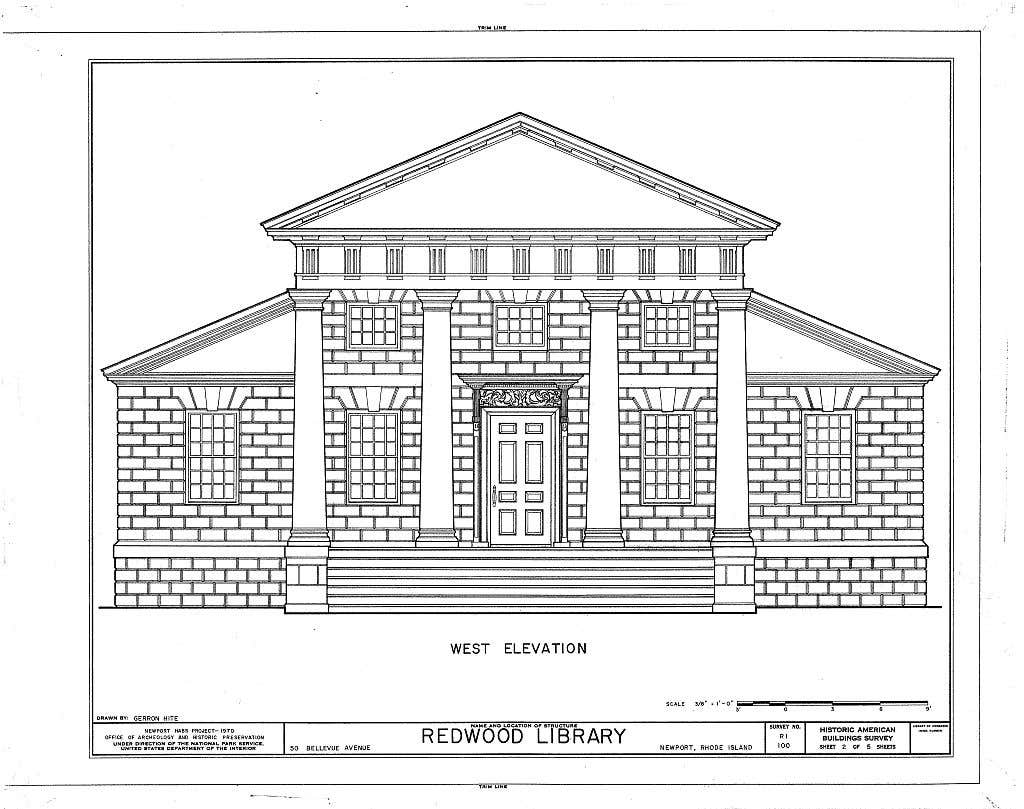

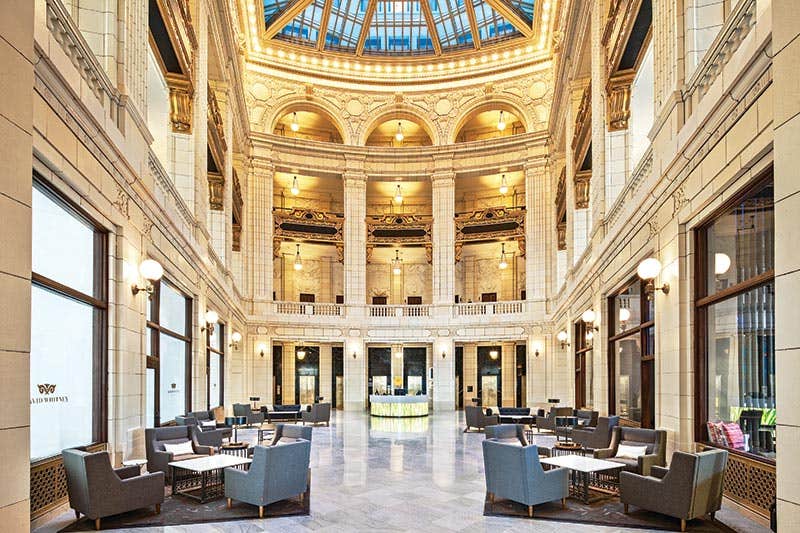

On a grander scale, The Roxbury Group bought and redeveloped Burnham’s David Whitney, which for nearly a century has stood as a gateway to Detroit’s downtown. Built in 1915, it was “modernized” in 1959 and closed in 1999. “A Gilded Age palace, its decline tracked Detroit’s trajectory of decline,” Di Rita says.

The $92-million project brings it back to life as a 136-room Aloft Hotel by Starwood, 105 apartments, 11,000 square feet of meeting and ballroom space and first-floor restaurants, bar and shops. “We dialed the exterior back to 1915 to re-Burnhamize it, and we preserved the four-story atrium inside,” Di Rita says. “It’s iconic and so much a part of Detroit.”

Detroit’s renaissance – just like the early 20th-century building boom – isn’t confined to the city’s center. Ronald D. Staley, senior vice president and director of The Christman Co.’s Historic Preservation Group, is experiencing this first-hand. At the north end of downtown, in what is called New Center, Christman Co. built the stately, Art Deco Fisher Building, which is commonly called “Detroit’s largest art object,” in 1928.

TOP PROJECTS

Detroit Cornice and Slate Co., renovated for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

The Christman Co.

Kresge Building (also known as 1201/1217 Woodward), restored for Bedrock Real Estate Services.

The Christman Co.

Malcomson Building, (also known as 1215 Griswold), restored for Bedrock Real Estate Services.

The Christman Co.

First National Building, bank repurposed as office building

Bedrock Real Estate Services

Detroit News Building, newspaper offices

Bedrock Real Estate Services

David Whitney to Aloft Hotel and apartments, The Roxbury Group.

Kraemer Design Group

Globe Building, one of the more recognizable structures on the east riverfront, has been transformed into the Outdoor Adventure Center

The Roxbury Group

Book Cadillac, conversion to Westin Hotel and apartments/condos

Kaczmar Architects Inc. of Cleveland

Fort Shelby Hotel, conversion to a Doubletree Hotel and apartments

Hobbs + Black Associates Inc.

Broderick Tower conversion to 124 apartments, first-floor retails and several floors of commercial space

Kraemer Design Group

McGregor Memorial Center Pool Restoration on Wayne State University, Quinn Evans Architects

UP AND COMING

Fisher/Kahn Buildings, Developer is Redico, in planning

The Christman Co.

1145 Griswold and other Capitol Park sites

Richard Karp, Kraemer Design Group

Wurlitzer Building, vacant 14-story office building being turned into a boutique hotel for young travelers, in progress

Quinn Evans Architects

Metropolitan Building, vacant office building to become extended-stay hotel, in design

Quinn Evans Architects

The Plaza, 12-story Mid-Century Modern office tower conversion to luxury apartments with first-floor commercial space, in construction

Quinn Evans Architects

Sugar Hill Venue, church being transformed to mixed-use restaurant/bar and small performing-arts center, in design

Quinn Evans Architects

Checker Cab, historic parking deck to become loft apartments with enclosed parking, in design development

Quinn Evans Architects

Christman, which opened its first Detroit office in 1915, also built the Detroit Masonic Temple (1926), the Maccabees Building (1927) and the Detroit Times (1929). The firm maintained offices in Albert Kahn’s 441-ft.-high limestone, granite and marble tower until the 1950s, when it, like many others, retreated to the suburbs.

Upon its return to the city in 2015, it moved back in, to a 6,000-sq.ft. office on the 26th floor – the Fisher Brothers’ own executive suite - that had been unoccupied for years. “We came back because things were rumbling,” Staley says, adding that “we realized there’s work you won’t get unless you’re in Detroit, and we wanted to be part of that excitement and rebuilding of the city’s spirit.”

The national landmark, called the Cathedral to Commerce, is only half full, and Christman is assisting with small repair projects for the owners, who ultimately hope to fully restore it to its original grandeur.

There’s a lot of work to be done: Most of the building’s systems have not been upgraded since it opened its doors. “Moving back into one of Detroit’s ‘crown jewels’ has not only been exciting, but working daily in our own restored space helps us to much more closely identify with customers who also want to save, restore and reoccupy the city’s heritage of these amazing historic buildings,” Staley says.

Gilbert, along with other developers, has begun doing new construction, which Knibbe says, “will be propelled by infill and historic buildings because they have proven the market. Our mid-century modern buildings will be the next to be done. We are already converting 12-story office buildings into high-end housing.”

Di Rita, Staley and Knibbe are confident that the future will continue to be bright. The big, sky-defining behemoths are either being finished now or will be in the next three to five years. “There are other major historic buildings still in need of restorations, such as the Book Tower, the Stott Building, the Metropolitan and the Free Press Building – but they are almost all in competent hands,” Di Rita says. “And we’re working on some of them.”

And this is just the beginning for Detroit's historical buildings. “The number of projects that are finished is few,” Staley says, “but the number in progress is huge. It’s an exciting time to be a restoration contractor and builder in Detroit.”