Palladio Awards 2016

Historic Doors’ Worshipful Woodwork at Bryn Athyn Cathedral

2016 Palladio Awards Winner

Special Award for Craftsmanship

Winner: Historic Doors, LLC, Kempton, PA

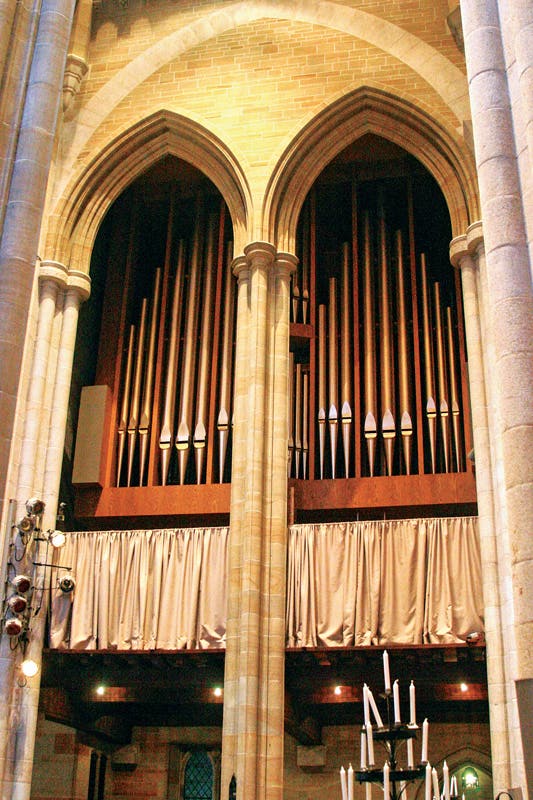

PROJECT: Chara Aurora Cooper Haas Pipe Organ Façade, Bryn Athyn Cathedral, Bryn Athyn, PA

Patron: Fred Haas through a gift from the Wyncote Foundation in memory of his mother, Chara Aurora Cooper Haas.

Designers: Steve Hendricks, Wendy Wyncoll, Historic Doors, LLC

Craftsmen: Jesse Dunkelberger, Justin Hendricks, Michael Hamm, Mark Hendricks, Historic Doors, LLC

Installing Contractor: Gurney Kerr Contractors, Huntingdon Valley, PA

By Gordon Bock

Among many devoted woodworkers, there’s an unsung credo that a project should be worth cutting down of a tree. Indeed, that might go double for historic buildings on the order of Bryn Athyn Cathedral (http://brynathynchurch.org/cathedral/), but no doubt Historic Doors LLC of Kempton, PA, has kept the faith by designing and fabricating a set of white oak, organ-pipe screens in traditional Gothic tracery patterns, prompting a special Palladio Award for Craftsmanship.

Says Steve Hendricks, owner of Historic Doors, “It was very humbling to receive the commission for new woodwork in such a well-loved building.” The charge was to create and install facades that fill two existing, adjacent, 25-ft. tall, pointed arches in the transept off the main body of the cathedral, as well as two secondary arches in the side aisles. “Our goal was to provide woodwork that would harmonize with the architecture of the cathedral, as well as the musical instrument to be installed behind it, and to draw upon as much precedent as possible so that the end result looks like it has always been there.”

No mean feat seeing as Bryn Athyn Cathedral in Bryn Athyn, PA, is not your garden-variety, neo-Gothic church. Constructed 1913-19 from an initial design by the legendary Ralph Adams Cram, with funds and property donated by Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company founder John Pitcairn, Jr., the building is the episcopal seat of The General Church of the New Jerusalem, based on the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg.

More importantly, its architecture is derived from a unique process that eschews conventional plans in lieu of a medieval design/construction collaborative of artisans and workers working from meticulous scale models. Wrote Cram in 1918, “Every new suggestion … was put in force, or further developed, until at last, by the time the walls had begun to rise above the ground, the system had reached a point of development never achieved at any place since the close of the Middle Ages.”

Despite the collaborative, open-minded heritage of the building itself, the idea of adding organ screens was controversial. Back in the 1970s the church had attempted to install a pipe organ that, like many such instruments, featured big, cantilevered turrets projecting out into the sanctuary. “Those organ pipes would have been right in the sightlines of the altar and nearby windows,” says Hendricks, “and the congregation was so upset that the project never went forward.” Even 40 years later, a new attempt at an organ resurrected the old, hard feelings, so much so that the Cathedral Director cautioned, “This is a very sensitive project that has been tried and then squashed.”

Fortunately, this was not Historic Doors’ introduction to the cathedral. “We already had done some prominent and successful woodwork that harmonized with the building,” says Wendy Wyncoll, Historic Doors designer, “so we think that’s why the patron and the church awarded us this project and were open to our proposal for a design.”

Indeed, design was the crux of the matter. Though the new organ (an instrument melded from two historic, decommissioned Skinner organs) would have over 3,000 pipes, they would be mostly invisible. “Our job was to frame what are known as façade pipes – that is, just the 24 or so show pipes in the arches that indicate there’s an organ there,” says Hendricks. So while the call was to not have the organ pipes overpower the sanctuary, by the same token the new woodwork could not dominate either. “As we got to researching what pipe organs look like around the world, it seemed the majority of designs and casings are pretty elaborate,” says Wyncoll.

Keeping Architectural Integrity

The challenge then was to make sure that the character of any new intervention maintained the building’s architectural integrity and purpose using materials and joinery methods that add to its craft tradition. “We wanted a traditional-looking composition that would have a top, a middle, and a bottom,” says Hendricks, “so in our design we suggested a capital, shaft, and base.” This tripartite design also has a practical side. “Behind that base are speakers for an electric organ, so we had to leave room for those speakers to sound through, as well as the pipes.”

Other windows in the cathedral have three lancet arches, but Hendricks and Wyncoll felt two would be better for obtaining a framed pipe space. These lancet arches carry a rose (a circle with Gothic decoration) but that raised a mechanical issue. “In stonework, you often seen lancet arches carrying a rose, which produces a hollow space where they come together,” says Hendricks. “We wanted a more elegant solution in wood, so we used a precedent from the quoir (choir area) arches at Canterbury Cathedral in England.”

Despite the fractious history of the new organ screen project, selecting a design went blessedly smoothly. “We had one major presentation to the Cathedral Director and the donor, making our case visually with examples from within the cathedral and other Gothic architecture,” says Hendricks. This included arguments for a base, body, and head, and that the arches should be filled with tracery. “We then presented the committee with three or four different tracery designs, hoping they would pick the one we liked, which they did.”

As mentioned, the largest arches are 26 feet tall by 8 feet wide, and the entire commission took about 14,000 feet of white oak to fabricate. To illustrate the massive scale, Hendricks points out that a section of the woodwork at the top is cut from 5-in.-square stock – almost like timber framing. “The nature of this tracery is that it’s all curves – nothing straight,” he says. “So we actually had to make tooling that allowed us to cut patterns and copes, both left-handed and right-handed.”

The work began with building a lot of careful templates on-site, then transferring that information to full-size drawings for fabrication. Each screen is assembled from three components: the tracery in the top, the tracery in the bottom, and the vertical pieces that connect them. “We have incredibly talented people in our shop,” he says, “and two of them spent six months, full-time building the screen – not including finishing and installation (which involved another contractor).” Adds Hendricks, “As much as we love working with classical buildings, it was amazing to have such a monumental project in the Gothic tradition. No doubt, Ralph Adams Cram would more than agree.