Features

Beyond the Call of Duty

Milton Grenfell's leadership in combating the proposed Gehry monument to Dwight D. Eisenhower is typical of his willingness to serve the public beyond his traditional practice.

By Gordon Bock

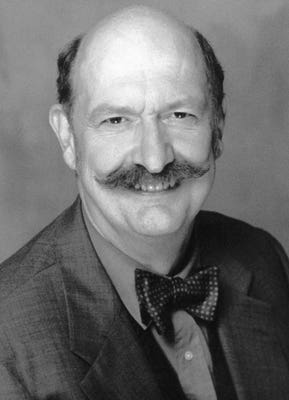

My spring started with a treat this year when I had the pleasure of visiting architect Milton Grenfell at his office atop the historic Barr Building, a 1927 Gothic Revival landmark in downtown Washington D.C. Piloting me between worktables, books and projects that run the gamut from mansions to civic monuments, Grenfell stopped abruptly to grab two hand-sized fragments of architectural stone lovingly repurposed as paperweights. "These are pieces of a medieval archivolt and foliated ornament given to me by colleagues," he announced proudly. "Imagine," he lit up, "a human hand-carved them in the 12th century!" A fitting image, you might say, for someone with a deep ken for traditional architecture, and this year's recipient of the Clem Labine Award.

Now in its fifth year, the Clem Labine Award honors an individual who, over an extended period of time, has fostered humane values in the built environment. As Labine himself explains, "The winning individual is one who is a living example of a life with a purpose, devoting time and energy to the creation of beauty and civilizing humanist values in public spaces." Though Grenfell is an architect and town planner working in the Classical tradition, Labine adds, "Milton won the award not so much for his personal architecture, but more for his civilized efforts in the public realm."

Indeed, as founder of Traditional Building and Period Homes magazines, as well as Old-House Journal, Labine knows whereof he speaks. He has been in the vanguard of the historic architecture movement since its inception, a dedication that extends to his longtime involvement with the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. "Milton is also being cited for his tireless pro-bono activity," continues Labine, "including his advocacy for changes in the Secretary's Standards for Rehabilitation and work with the National Civic Art Society – in particular, articulating the shortcomings of the ill-conceived Eisenhower Memorial." (More on this later.)

No surprise then that Grenfell takes a wide-ranging view of his practice and architectural philosophy.

When asked if he calls himself a classicist, he shoots back, "Yes, but in the broader definition of the word – that is, the best and most enduring of an artistic tradition." Classical has another meaning, he explains, which includes the Greco-Roman tradition. "But I'm not limited to that," says Grenfell. "Gothic is a Classical art form as well."

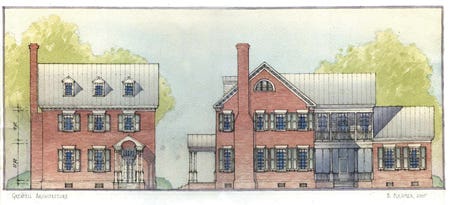

In fact, as I survey the walls of his office, I note they're push-pinned with lovely watercolors and renderings of projects large and small, from residential to commercial to whole blocks and campuses. My eye catches a pen-and-ink town plan of what appears to be a small port city from the colonial era. In reality, it's the modern community of I'On in Mount Pleasant, SC, designed on the New Urbanist model. "It's named after a Charleston hero from the 18th century," says Grenfell, as he points out a pair of winged cherubs in suspended flight, "so we thought a period treatment would be appropriate, with putti holding up the legend, in Latin." Below them, a "great leviathan" Columbus might recognize from his maps spouts offshore in an open expanse of paper.

Traditional Epiphanies

Clearly, you don't become an architectural omnivore like this in one bite. "There have really been two early threads to my career," reflects Grenfell. "One is that I grew up in a 1920s garden suburb in Jackson, MS, with a neighborhood center right within biking and walking range of my house. It was all there – bookstore, drugstore, grocery, a complete retail center – and with almost everything else one might need: churches, bakery, school, dance studio, barbershop, banks – you name it. The second thread is that most of the houses in my neighborhood – and all of the beautiful ones – were 'pre-war.' So I grew up loving traditional houses and traditional urbanism."

However, he says even after gravitating to practicing traditional architecture, he sensed a loss in the built environment because of ongoing urban sprawl and the abandonment of traditional towns, cities and neighborhood centers. "So when I discovered New Urbanism, thanks to Peter Calthorpe and Andrés Duany, that was the missing piece. Suddenly I had a macrocosm of traditional urbanism to accompany the microcosm of traditional architecture I had been working in, which is to say a complete return to traditional ways of building – not just individual structures but entire communities. What many New Urbanists are really purveying is traditional urbanism, so I felt as drawn to that as I did traditional architecture."

Traditional architecture can be a powerful personal inspiration, but in the 1960s and '70s it was an elusive notion to build a career on. "I didn't get it at school, I'll tell you that," recalls Grenfell. "As a student at Washington University in St. Louis, the professor gave my class an exercise that for me was a real eye-opener. It was a sketch problem, to design a large, ceremonial room for a Scandinavian consulate on the coast of Northern California. Basically, it was just a rectangle of space; it had no program; it was just a ballroom."

As Grenfell continues the tale, he sketches an interesting sea-change in our culture as well as in his architectural education. "At that time, belief in Modernism – what some would call the high modernist classicism of Edward Durrell Stone and the Brutalism of Paul Rudolph – had kind of run out of gas. So we were trying to get interesting buildings through program – that is, the statement of conditions and objectives for a building project." But the poverty of this approach revealed itself in the assignment when Grenfell and his fellow students had no program to manipulate.

So logically he looked for a solution in Scandinavia with architects like Alvar Aalto. "I had lots of big skylights, lots of big windows open to the Pacific and, of course, exposed wood and glulams for the structure. At pin-up though, the professor cast a disappointing eye on my proposal. 'I don't understand what makes that a ballroom?' he said. 'Why couldn't it be a gymnasium?' Chagrined, I acknowledged, 'Well, you're right, I suppose it could be.' So then and there I realized that program manipulation alone could not make a room. The tools of Modernism had left me no way of making a grand room."

The way to make such a room, however, turned out to be not ahead of him, but behind him. "Feeling little hopeless, I walked up the hill to the university's tea room," Grenfell continues, "housed in what used to be the main reading room of a 1904 library built by Cope and Stewardson." He goes on to describe a Georgian, English Baroque, great room with all the requisite details: high, ornamented ceilings; decorative plaster; deeply inset double-hung windows, oak paneling and a carved Missouri walnut fireplace mantel.

"This is the room!" he recalls saying to himself, "but I have no idea how to do this!" Moreover, he had been told that all the craftsmen were gone, the work was unaffordable and, being 'not of our time' such a room was intellectually untenable. "I kept believing these excuses but, after several years of practice and involvement in preservation, I came to the conclusion that we could build rooms like that again. More importantly, we had to. What we needed was to figure out how to do it."

Here, the threads of new and old intertwined again for Grenfell. "It was historic preservation and working with old structures that kind of led me back to the good old ways of building, and the true profession of architecture," he says. He explains that he got involved with preservation at an early stage, including starting the preservation organization in his home town. Then, upon moving to Charlotte, NC, he served on the preservation commission for six years. "I was always campaigning to save some building somewhere – at times, literally standing in front of wrecking balls! Thankfully, most people are wised up now."

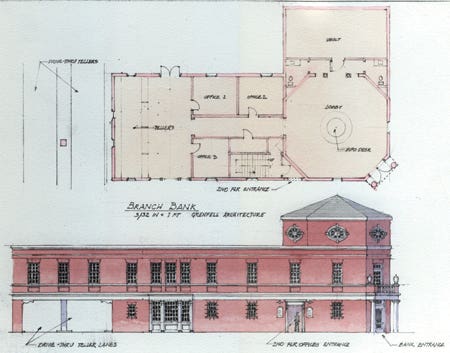

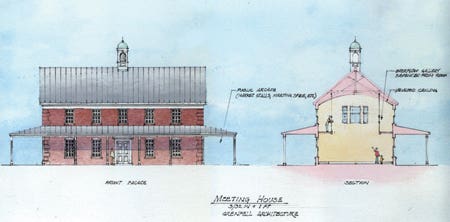

All this makes a good tale of an architectural enlightenment, but in Grenfell's hands the experience clearly has practical applications for today. He shows me a proposal for an adaptive re-use of a 1950s branch library to be converted into a post office. "This started out looking like a brick version of Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye," he says of the original façade. The watercolor in his hands, though, might be described as a Classical make-over in brick, replete with ionic brick pilasters, glass-fiber reinforced concrete cornice and cast-stone architrave. In no way archaic, it is confidently traditional in a subtle, timeless manner.

In the same sense, elevations for an addition/renovation to a former National Park Service building in Philadelphia, PA, now contemplating new life as The Museum of the American Revolution, show a similar thoughtful metamorphosis. The arcaded central front salient Grenfell points out is no mere stage-set of iconography. "Here visitors can gather to come and go from tour buses," he explains, "out of the sun or rain before proceeding inside or boarding a bus." And for those who think Classical or traditional are code words for inflexible, there's this remark. "When they asked if we could design an aesthetically satisfying two-story building, to which and equally satisfying third story might be added later, we said Sure! and quickly found a way."

The Eisenhower, the Better

For a man with Grenfell's interests, the public realm clearly does not stop at roofs and walls, or even open spaces, but inhabits the world of words and ideas as well. "Milton is a man of strong – often controversial – opinions," explains Labine. "He doesn't mince words, and isn't afraid to stand up in the public arena and do battle for what he thinks is right. He believes what he believes, and he has passion, which is a good thing."

Passion may be an understatement. While Grenfell is among the most courteous, erudite and articulate people you'll ever meet, after a few minutes conversation, it's more than evident he's emphatic about architecture. "Absurd," "ghastly," "blatantly ugly," and "ridiculous" are as much a part of his vocabulary as "meaningful," "handsome" and "exquisite" – not to impress the listener with invective or verbally skewer an opponent, but simply to make his point crystal clear.

Grenfell does not impress as an elitist either. In his office, I look over his shoulder at a photo of a tall modern office building, whose masonry curtain wall is improbably interrupted by a band of glass windows half-way up. "Materials should look like they can do their job against gravity," he shakes his head. "The public intuitively knows when something in a building doesn't make sense. Willfully transgressive buildings like this only add to the public unease!" No believer in the Emperor's New Clothes syndrome here.

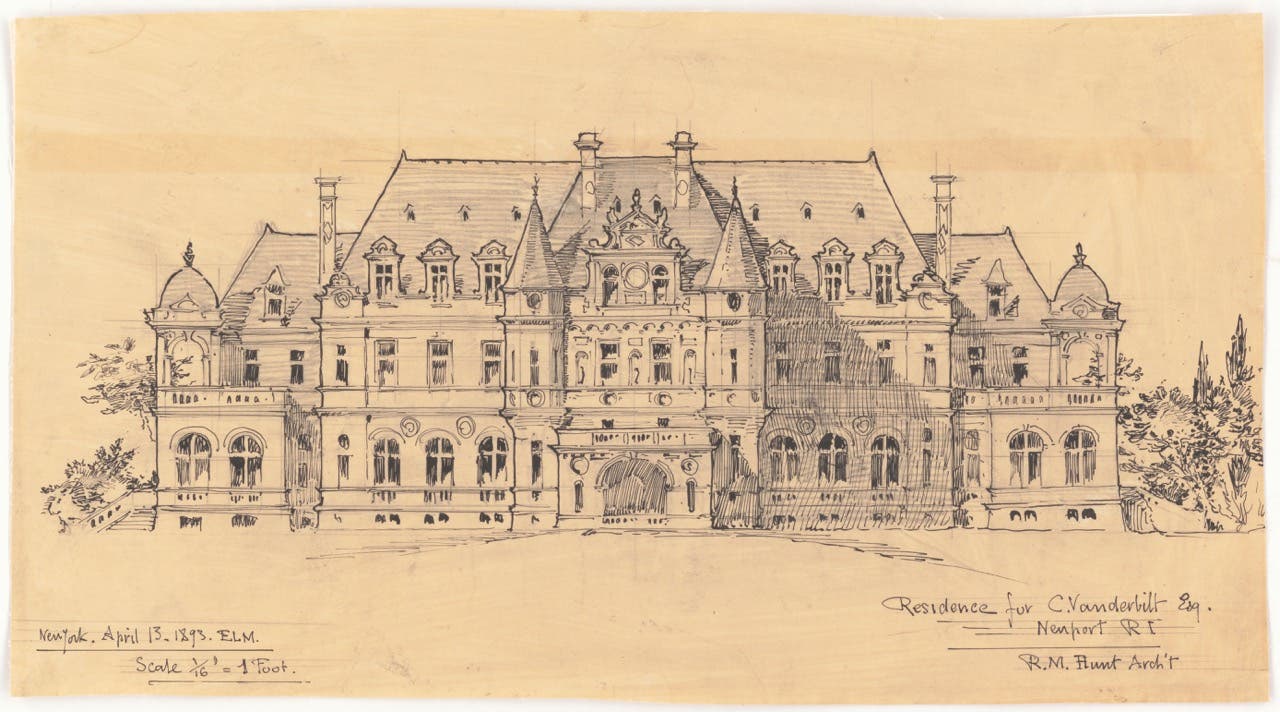

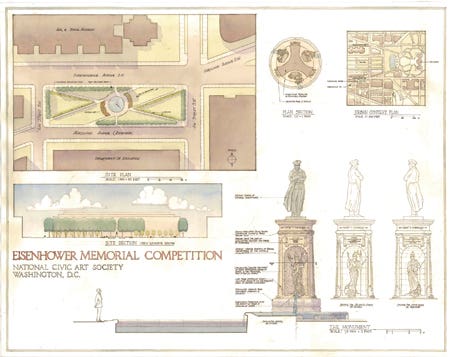

Which bring us to a prime example: the competition for the Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, D.C. Recalls Grenfell, "Going back about three years ago now, my colleague Erik Bootsma and I were grousing about an image of Frank Gehry's proposal for a monument to Dwight D. Eisenhower." The proposal at the time was abstract and based on monoliths right next to the National Air and Space Museum. "We really should have a traditional counter proposal competition for this thing!" Grenfell remembers saying.

"Traditional proposals would present a very clear alternative to this nonsense, and start a public conversation about the nature of monuments." As he further explains his point, "Washington has many beautiful traditional monuments, but the Modernist movement has also left the city with a host of repellent and meaningless buildings and monuments. Politics aside, it's also a city most Americans care about, making it the ideal place to have such a conversation."

So, over the course of six months they rounded up support from the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art and the National Civic Art Society, the latter who ran the counter-proposal competition. "We got close to 40 entries and, luckily, Susan Eisenhower came to our exhibition and reception and was quite taken by it," says Grenfell. "Perhaps she, like most Americans, probably never seriously considered a traditional alternative to a modern memorial. For many people, it is as if 'that was then, and this is now.'"

Labine notes that in the beginning, the Eisenhower was not an open design competition. "Very few people knew about it," he says, making it "sort of a 'stealth monument.'" Where does the design for the monument stand today? "We've tapped into a great reservoir of sentiment," says Grenfell, "and, hopefully, we can get a new competition that will also allow for traditional proposals." Since one of the meanings of "public" is exposed to general view, that sounds right up the public alley.

Gordon Bock is co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com) and is available for keynote speeches, seminars and workshops through www.gordonbock.com.