Palladio Awards 2016

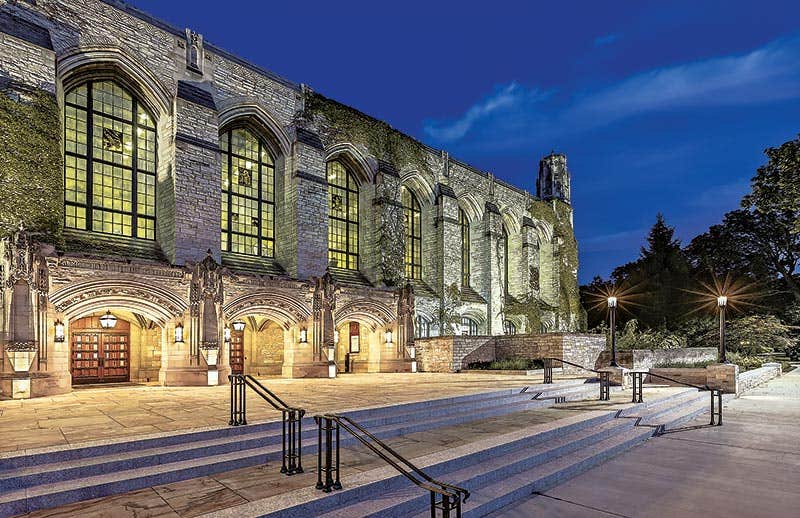

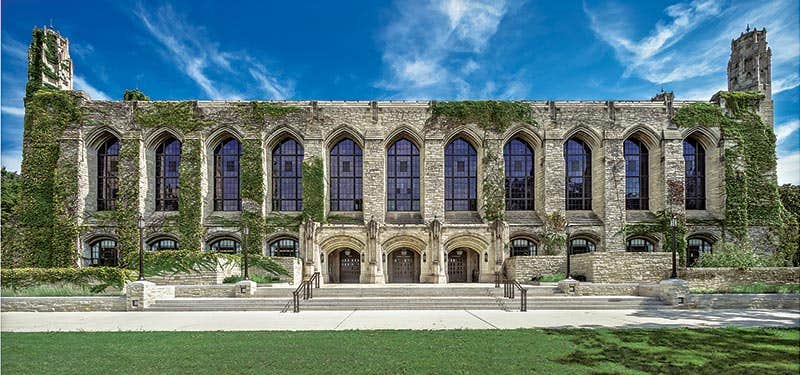

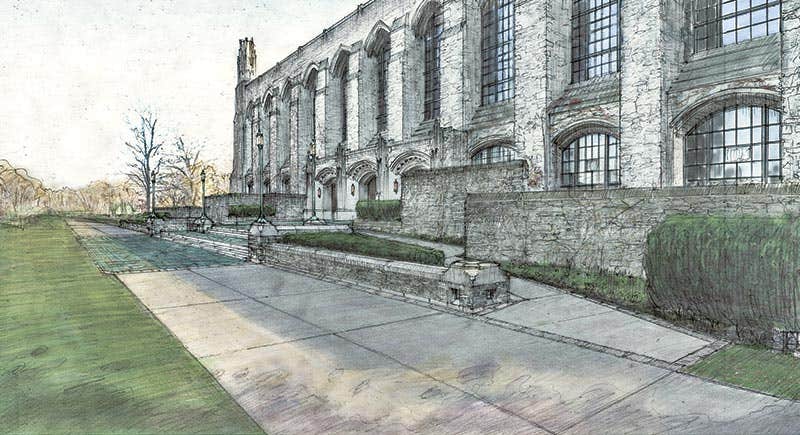

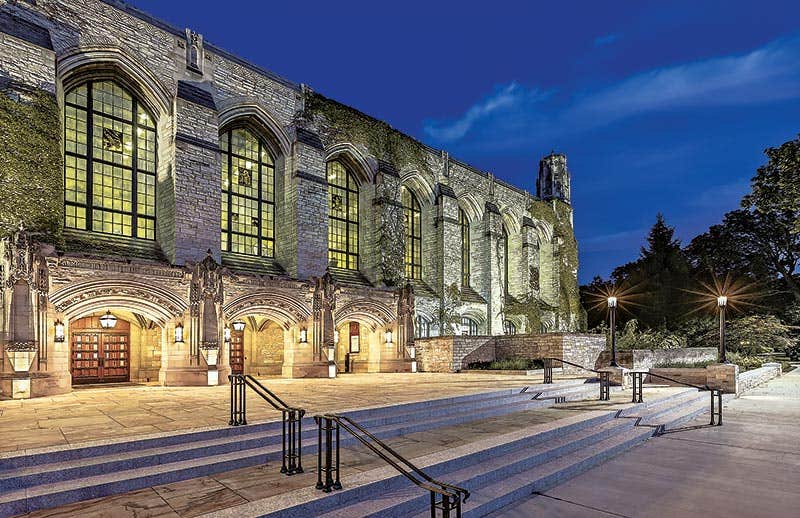

HBRA Architects Restore the Charles Deering Library’s West Entry

2016 Palladio Awards Winner

Restoration & Renovation

Winner: HBRA Architects, Inc., Chicago, IL

KEY SUPPLIERS

Millwork and Carving: Barsanti Millwork, Chicago, IL

PROJECT: Restoration of the

West Entry, Charles Deering Library, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL

Architect:HBRA Architects, Chicago, IL; Aric Lasher, FAIA, President and Director of Design; Dennis E. Rupert, FAIA, Principal in Charge; William J. Kinane, Jr., Project Architect

Archival Casework: Small Corp, Greenfield, MA

Ornamental Ironwork: O’Brien Metal, Chicago, IL

Stone Supplier and Fabricator:Quarra Stone Company, Madison, WI

Lighting:Anne Kustner Lighting Design, Evanston, IL

By Gordon Bock

Designed by James Gamble Rogers in the Collegiate Gothic style, the Charles Deering library opened in 1933 and served for decades as Northwestern’s main library, as well as a cathedral-like campus landmark. In 1970 when the University built a research library right next door, they permanently closed Deering’s front entrance and re-routed access through a basement corridor that connects the two buildings.

“Deering Library wasn’t really sealed up; it was still in use,” explains Aric Lasher, FAIA, HBRA President and Director of Design, “but it no longer had its own public face or public presence.” What’s more, the remaining entrance, such as it was, took a circuitous route below grade. “So the idea of the West Entry restoration was to improve the setting for the building and reopen it to the public.”

Construction of a new, accessible-entry route and plaza is a signature feature of the West Entry restoration, so matching the existing stone and masonry work of the 80-year-old library was critical. “On the building exterior, there is a mixture of seam-faced and vein-cut Lannon stone, a very dense Wisconsin limestone,” say Lasher. It’s the same material, he explains, but one with many beautiful variations that was obtained for use in the landscape walls from the same quarry as the library.

He adds that the carved limestone elements on the exterior contribute a different character, and are used in the building loggia as well as some of the interior stonework. “Many of the original materials are local – at least Midwestern in origin,” says Lasher, “and though we had some difficulty locating exactly the same granite for new copings and stair treads, we found plenty of good sources for a compatible match.”

The Plaza

Sourcing slab stone for the plaza, however, was another matter. As originally specified, the material was a very figured, variegated, dense-structured sandstone. “It’s beautiful, and used extensively in the United States Capitol and government buildings in Washington, DC, but the only place we could see it at Deering Library was in the original drawings.” Turns out, all of the original paving stone had been removed over the course of minor renovations of the porch area, leaving no extant examples. What’s more, the quarries for the DC buildings are owned by the federal government exclusively to maintain a ready source for repair and replacement stone. “So we found our stone through a company that sources materials from all over the country, and has always done a magnificent job matching difficult materials for our stone building projects,” Lasher adds.

The new plaza, which fronts nearby Deering Meadow, not only includes custom-designed lamp standards and railings and new landscaping, but also ADA access. “Rather than ramps with railings, or some other sort of intrusive, asymmetric element, we have very gradually sloping walkways that lead from the main pedestrian thoroughfare up to the plaza level on either side,” says Lasher. “They work with the overall design and ensemble of the entry plaza in a way that doesn’t feel like an accommodation for the disabled. Able-bodied people use those ramps probably as much as they do the steps.”

Lobby Challenges

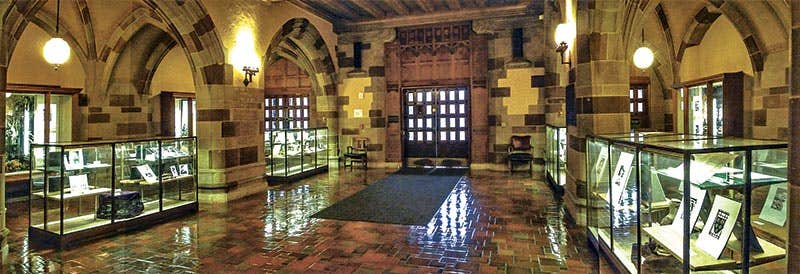

As the project progressed to interior, work on the lobby it took on extra, intangible challenges. First, the client required that the library not be vacated during construction, and the spaces at both the north and south sides of the entrance hall had to remain available to the public. Second, any new work would not be obvious.

“The client’s wish was that there’d be no visual disparity between the quality of the new work and the original architecture of the Rogers building,” says Lasher. Or, put another way, their goal was to not to follow a “nod to the future and a nod to the past” approach in introducing modern elements. “Because we were familiar with a high level of finish, and work with craftspeople who are capable of providing that level, we were able to both modify and add to the existing stonework and woodwork in the lobbies without any apparent fingerprint – even though the scope of the work was significant.”

Nonetheless, there were some twists to seamlessly restoring and upgrading the lobby while staying consistent with the rest of the 80-year-old building. “James Gamble Rogers often mixed materials in his buildings,” explains Lasher, “to give them not just a varied look, but also the appearance of age.” In the Deering lobby, for example, limestone and sandstone are combined for an almost polychrome effect.

Lasher notes that at Yale, Rogers built buildings with a very porous limestone that absorbs dirt and thus can take on the ambiance of age very quickly. “The idea was to give them a sort of ready-made venerability – and charm,” he explains. “This wasn’t the first Rogers building we worked on, so I think our learning curve was less than for someone who was unfamiliar with his work.”

Even so, very real accretions were a genuine problem. “People had smoked there for 60 years and the surfaces, which, in addition to stone, include ornamental stenciling on the plaster ceilings, were covered with nicotine stains.” In response, the firm worked with a stone restorer who cleaned the interior stone with a poultice method. “Once cleaned, the lobby went from being a dark, kind of lugubrious space to something light and much more uplifting.”

The Collections

New components and mechanical systems were essential if the recommissioned lobby was to be functional and up-to-date, not to mention museum-grade. “The idea was to turn the lobby – which wasn’t being used for much of anything – into a space that could showcase the library’s collections. However, for that to be possible it would have to meet certain environmental standards; otherwise other libraries wouldn’t lend archival materials.”

Besides adding a custom-designed desk station for building security, which had never previously existed, the work included refurbishing four existing glass display cases, or vitrines, and creating four new matching, archival-quality display vitrines out of hand-forged antique iron.

Though the West Entry is only the initial phase of an overall restoration of the library, it included upgrades to mechanical systems that required creativity, as is often the case in historic buildings. “We had to work with the existing mechanical systems in the building,” says Lasher, “making sure that they would perform adequately, not only for user comfort, but also to avoid compromising the archival materials being displayed.”

Repair, reconstruction and re-lamping of period fixtures was just part of the process. “We worked with a lighting design company who was able to augment the actual lighting component of those fixtures without changing their appearance, so that their lighting characteristics were either more appealing or better suited to their new use.” Lasher says they were also able to conceal new uplighting in some ornamental millwork elements within the lobby. “It’s very subtle and doesn’t look like a modern lighting intervention, but it does provide a higher level of illumination in what were dark corners of the spaces.”

Part of the overall program was also to improve the accessible route through the building and its connection to the later main library. “Formerly, you never quite knew when you were leaving the 1970s building and entering Deering. The corridor felt like somewhere you weren’t supposed to be, as if you had wandered into a back-of-house area.” The firm’s solution was to design an entryway and corridor with a clear sense of transition to Deering Library. “Now there’s a portal that feels like part of Deering, so a visitor experiences a very clear demarcation between the two buildings and their identities.”